If the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s timing of “Matisse: In Search of True Painting” was designed to capitalize on this reliably annual tendency, however, I have to say I don’t have a problem with it. Viewing the show in late December, a few weeks after it opened, I found it an excellent and hopeful bolster to the perennial year-end process of considering achievement and improvement—whether in life or in art.

The key notion that this exhibition puts forth is that painting rarely came easily to Matisse. (This despite the fact that critic Clement Greenberg called him a “self-assured master who can no more help painting well than breathing.”) Using 49 canvases, many of them made in pairs or series, the exhibition suggests how hard Matisse worked to progress from one painting to the next, generating several versions or revisions of a given subject before hitting on the “best” or “finished” one.

Granted, many artists work in series, and revision is a key part of any creative process—the special thing about this exhibition, though, is how it puts those revisions and multiple attempts on view, rather than confining them to the studio or splitting them off from each other as orphaned individual pieces.

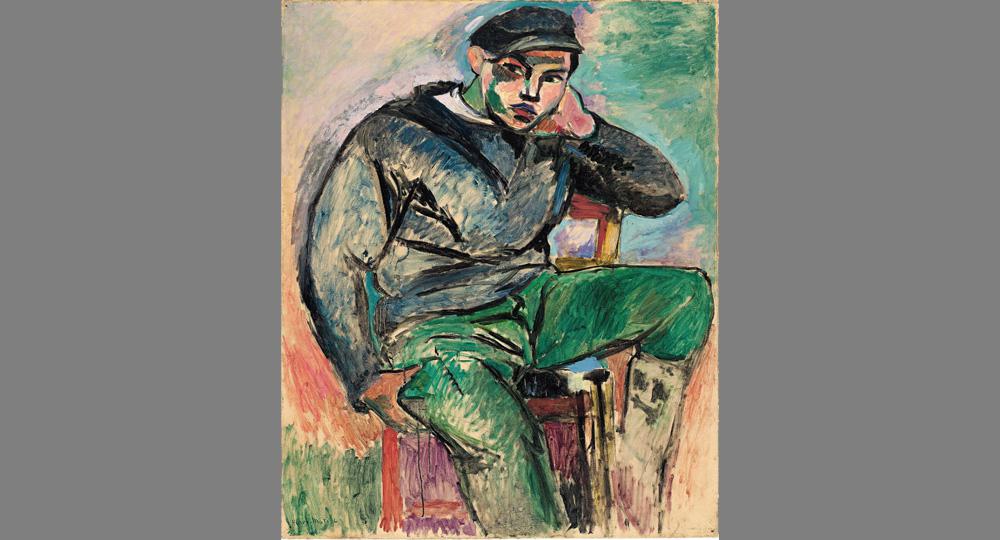

In the first few rooms of the exhibition, for instance, one sees 1904–5 still lifes Matisse painted of identical scenes, but in different styles. Also on view there from 1906 are Young Sailor I, a fauvist style portrait, and Young Sailor II, which takes a flatter approach. (Interestingly, the uncertain Matisse initially told his friends that Young Sailor II had been painted by a local postman.) And an early highlight, hung side by side, are three versions of his large-scale painting Le Luxe: one a pencilled cartoon, one a softer version in oil, and one the final, more graphic 1907–8 version created using distemper.

As we also learn in this exhibition, Matisse himself endeavoured during his lifetime to put the messy process behind his finished paintings on view. In the 1930s, he hired a photographer to document his process on certain paintings, and in 1945, he held an exhibition in Paris that showed six finished paintings alongside substantial black-and-white photo-documentation of the various stages they went through. The Met has helpfully recreated three walls of that 1945 Paris exhibition, and the museum has also installed one other painting alongside its related time-lapse-evoking documentation.

Overall, “Matisse: In Search of True Painting” heartened me with a reminder that what is genius to one person may simply be hard work to another. Renewing the everyday—as well as the intention to create every day—were a couple of themes that came to mind while taking in the show. Also evoked for me were process as an equal companion of product; life’s varied, if sometimes hard to see, opportunities for redemption; the rewards and trials of experimentation; and the necessity of risking failure and embarrassment in order to move forward.

Part of me remains cautious, of course, about attributing too much thematic meaning to this assemblage of objects. When shown earlier this year at the Centre Pompidou and the Statens Museum for Kunst, the exhibition was simply titled “Paires et Séries” (Pairs and Series) and “Fordobling og Variation” (Doubles and Variations), respectively, forgoing the placement of any existential “search” front and centre. Matisse’s seriality is already well-known by many, so I’d guess that someone more expert in his oeuvre might not be as personally wowed by the exhibition—particularly given that it is fairly compact and concise, and could be bigger. Furthermore, there is little allusion in this show to Matisse’s sculptural practice, which many also credit with his progress forward on certain paintings.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that I enjoyed this exhibition quite a bit—and I do hope to remember its lessons for a few weeks yet, even as the buzz of a new year’s promise quickly fades from view.

Henri Matisse Young Sailor I 1906 © 2012 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse Young Sailor I 1906 © 2012 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York