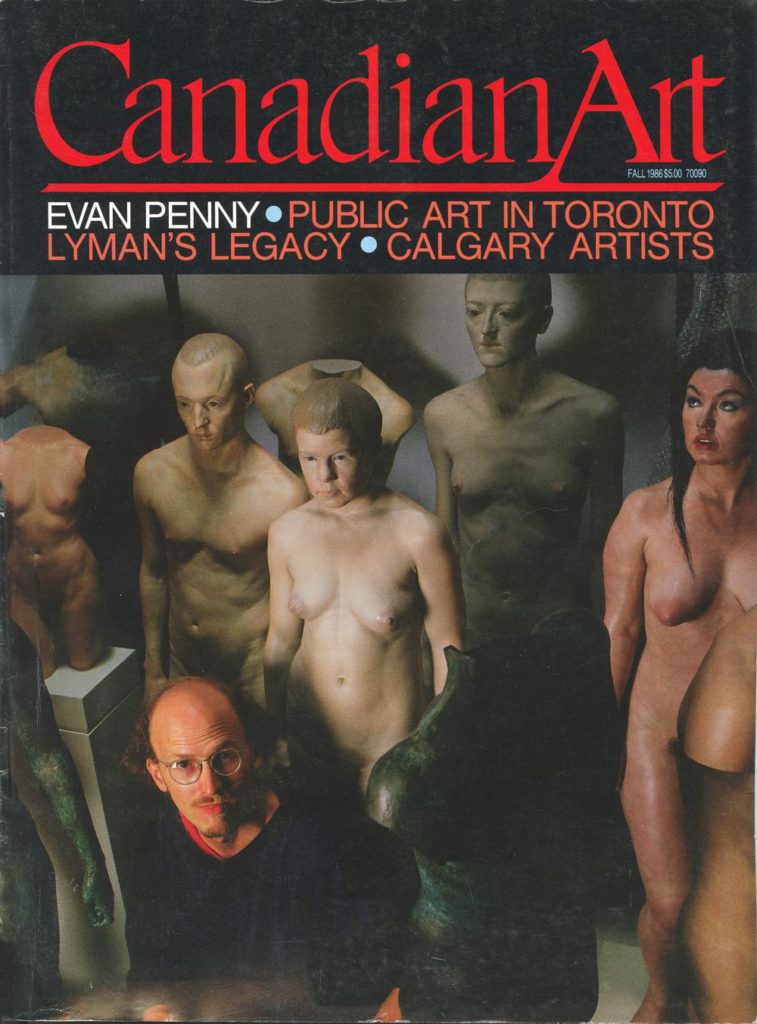

Evan Penny is building his career as an artist upon one central and absorbing problem: how to Make It New when you’re making figurative sculpture. Figurative sculpture, moreover, of a particularly high mimetic cast. That he is succeeding in keeping traditional sculptural forms meaningfully alive and continually inventive is a tribute to his tenacity as an artist. That he is bringing to ground (indeed to their grassroots) some perennially useful questions about the nature of sculpture itself keeps him, at this time in the bedazzling history of postmodernism, authentic.

His authenticity as a maker of genuinely new works tends to steal over viewers of Penny’s sculptures even as they are preparing to relegate them all to the trash-bin of academic figuration. Painter John Scott told me recently how impressed he had been with the fate of Penny’s sculpture Ali (1982-84) at the hands of his class of hard-to-please determinedly avant-garde students of the Ontario College of Art. Scott was escorting them through the six-gallery progress of the great sprawling New City of Sculpture exhibition held in Toronto in the summer of 1984. When they fetched up at Gallery 76, Ali stood out from the welter of nervous constructions in papier-mache and plywood and neon and cast-off clothing like a Ming vase at a jumble sale. As one voice the students condemned it to the shades of the retrogressive. It was only after an hour with the frangible fashionability of the rest of the work, Scott pointed out, that all the students came back to Penny’s compelling little figurative piece, as the sculpture that seemed to all of them the hardest to crack, the least exhaustible, the most fulfilling.

Why this should be is an absorbing story.

So begins our Fall 1986 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.