In mid-June, the much-anticipated Esker Foundation opened its doors in Calgary with “The New Alberta Contemporaries,” a roundup of works by 47 recent graduates from art schools across the province. Founded by local art patrons Jim and Susan Hill, the Esker is the latest in a growing trend of privately funded venues for contemporary art in Canadian cities—notably including the Rennie Collection in Vancouver, the DHC/Art Foundation (and its recent offshoot, the PHI Centre) in Montreal and Arsenal art contemporain in Montreal and Toronto. None are commercial or collecting institutions in the traditional sense, yet all are ambitious, with impressive programming and gallery spaces that have quickly become dominant art-scene forces both locally and nationally. They seem to work as alter egos to big public museums and galleries, focusing on the presentation and incubation of new art practices in a delicately mixed model of business and philanthropy.

“The gallery is a gift to the community and I thought something really grand could take place here,” says “The New Alberta Contemporaries” curator Caterina Pizanias over the phone from Calgary. Over the course of two years, Pizanias—a sociologist of art who graduated from the University of Alberta and has taught at the University of Calgary—toured the province, visited studios and, in conversation with student artists, selected works that best sum up their particular circumstances and concerns. “Here in Canada and North America we keep producing more and more fine arts graduates when the art market [and] arts funding are shrinking,” she explains. “Nobody stops to say, ‘Okay, how will these graduates establish themselves after school?’”

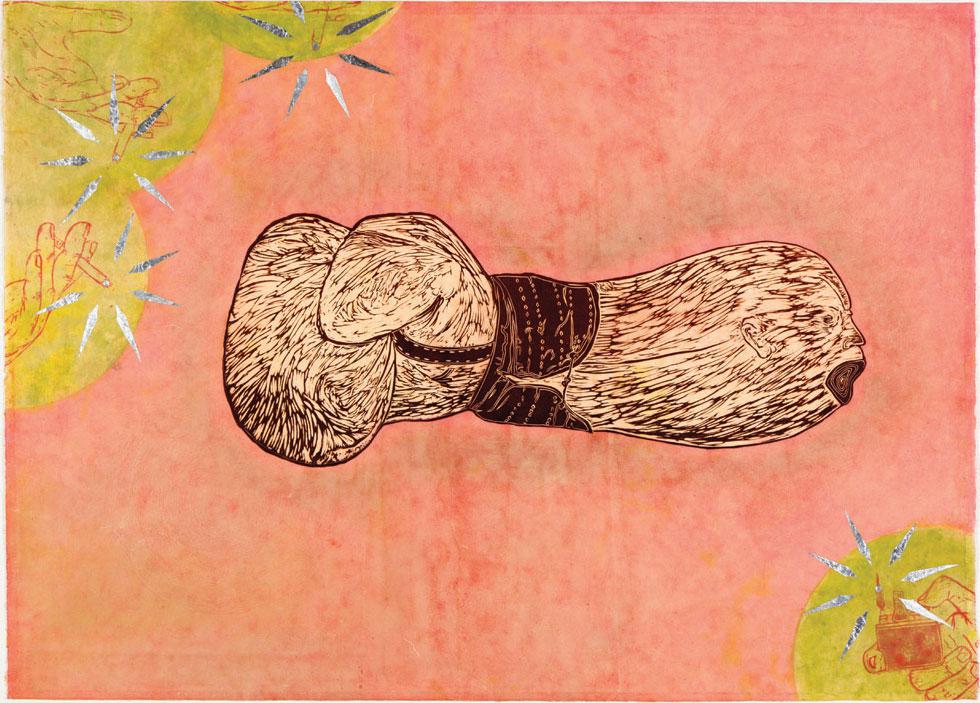

In a bid to answer that looming question, Pizanias sees the exhibition as a kind of springboard for emerging artists and purposely chose to forgo an overarching thematic structure for the exhibition in favour of a more democratic rubric: “I decided that in the exhibition there would be no identifying marker that places the artists to a school, a degree or a year that the work was done. I want people to look at the art without those attachments.” That’s not to say that there aren’t complex issues that underpin much of the work on view. “If you were to go and see young graduates working in Europe, everything is political in the sense of economic crisis, in the sense of migration,” Pizanias notes. “We are protected from those ‘political’ crises here. Most of the themes start from personal issues and then expand to talk about what the oil industry is doing to the land in Alberta, or what it might do to national parks, or to the extinction of species. They are very, very thoughtful, even if the issue is personal.”