The drama of group interaction—from the life of the party to the couch of therapy. The lust to possess another person completely. The delicate and dangerous search for self.

All of these are themes that come to mind when considering the paintings of Eliza Griffiths. In her figurative works, she concocts characters who come across as alternately clownish and careful, vicious and vulnerable.

“The theme that has been emerging for the past while is trying to heal dysfunction and trauma,” Griffiths tells me over the phone. “But the humour sort of mediates it, and is a way to deal with darker subject matter.”

New instances of this practice are currently on view at Ellephant in Montreal until December 17. And in this most recent chapter of her work, Griffiths says she finds herself trying to be freer and less constricted, and a little less distant from the viewer.

“The show is called ‘Acts of Love’ or ‘Actes d’Amour,’… the characters are bodies or agents helping each other” with “the idea that one body affects another body,” Griffiths says.

And while her paintings have long articulated the fluidity of gender and desire, particularly for women, Griffiths says the works at Ellephant address love more directly than she feels she has before.

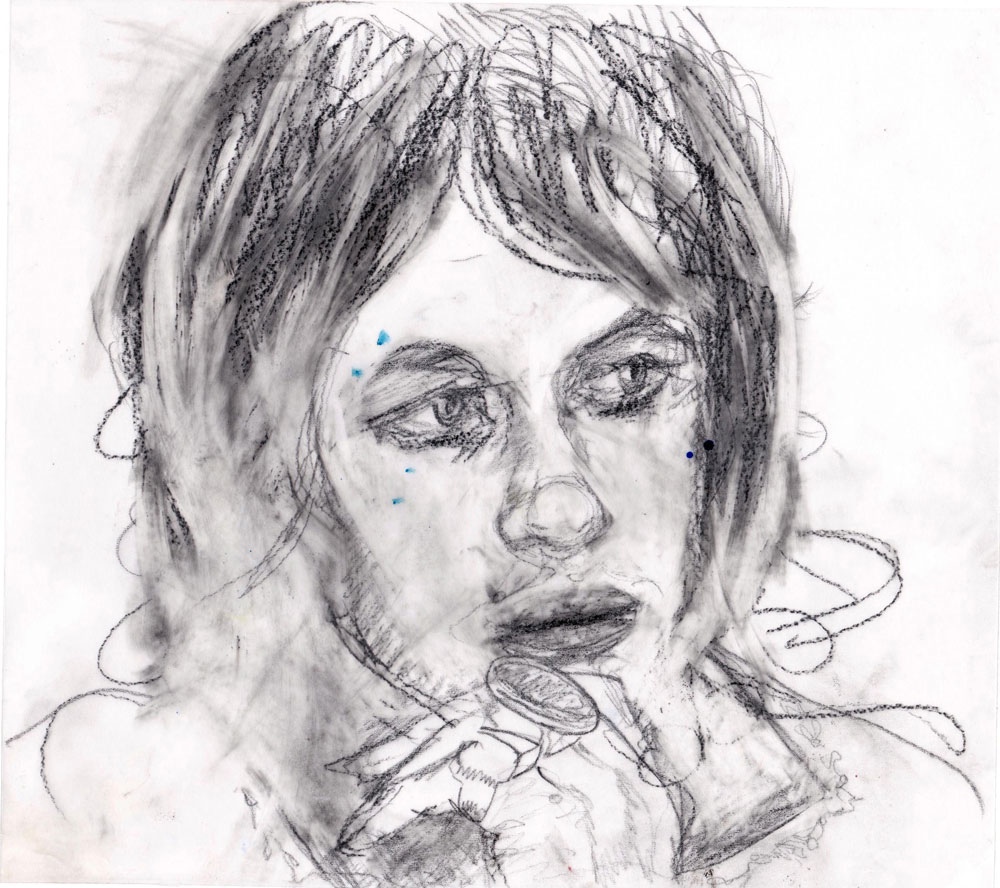

Eliza Griffiths, Party, 2016. Mixed media on vellum, 102 x 114 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Party, 2016. Mixed media on vellum, 102 x 114 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

“It was more about not being embarrassed by the l-o-v-e word,” says Griffiths. And this in itself presented its own kind of risk: “How do you do that in a figurative painting and not make it corny?” she asks. “The dangers of being sentimental or hackneyed with figurative paintings are really high; I think that is really true of figurative sculpture too. It can be a bit of a minefield. ”

The veteran artist also teaches at Concordia University—most recently in courses on portraiture, which is a switch; though her paintings are figurative, they are not portraits per se. Lately, she has also been wondering to what extent painting itself can be a helping gesture.

“I was thinking about doing the paintings as a kind of ritual performance, of imagining one can help someone else through gestures and intentions and conjuring,” Griffith says.

When I ask her about the presence of another kind of ritual pictured in her past work—therapy—Griffiths explains her interests readily.

“Therapy is an ongoing theme I am interested in, because I am so interested in the mind and brain,” says Griffiths. “I do a lot of research in neuroscience and I am personally really into psychoanalysis.”

To Griffiths, in part, therapy is also a particular kind of dramatic scene in which she can situate her characters.

“I love the visual narratives of psychoanalysis as a sort of theatrical setup,” Griffiths says. “It is a space that nobody ever sees—it’s a totally private interaction.”

Eliza Griffiths, Thinking, 2016. Print, 102 x 114 cm.. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Thinking, 2016. Print, 102 x 114 cm.. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

There are class implications there, too, she acknowledges.

“It’s a super-bourgeois thing to have a shrink, but it is still very private in Canada,” Griffiths observes. “When I showed [some shrink paintings] in New York, they thought it was totally normal, but in Montreal, they thought it was totally brave, as if it was direct autobiography.”

On the lighter side of things, Griffiths’ exhibition at Ellephant opened not only with a drag king band performance, but also with an activity rarely seen at art openings—face painting.

“It was [Ellephant director] Christine Redfern who set up the face painting, and it was a visual artist, Caro Caron, who did it. She is great. It was really fun,” says Griffiths.

In terms of what’s next, Griffiths is looking forward to exploring art and therapy in an “expanded field” of practice—that is, possibly off the canvas as well as on it.

“I do have an ambition, whether it is fulfillable or not, to open up dialogues about awkward things in human subjectivity, and make them sharable in a strange way,” Griffiths says. “I would be super-happy if people sat down and shared with each other in front of” the group therapy painting, for instance.

“That is sort of where I’m going, where the works have a sense of inviting viewers to use it as a point of departure for dialoguing about emotional vulnerability and the need for inclusion.”

“Eliza Griffiths: Actes D’Amour” continues at Ellephant in Montreal until December 17.

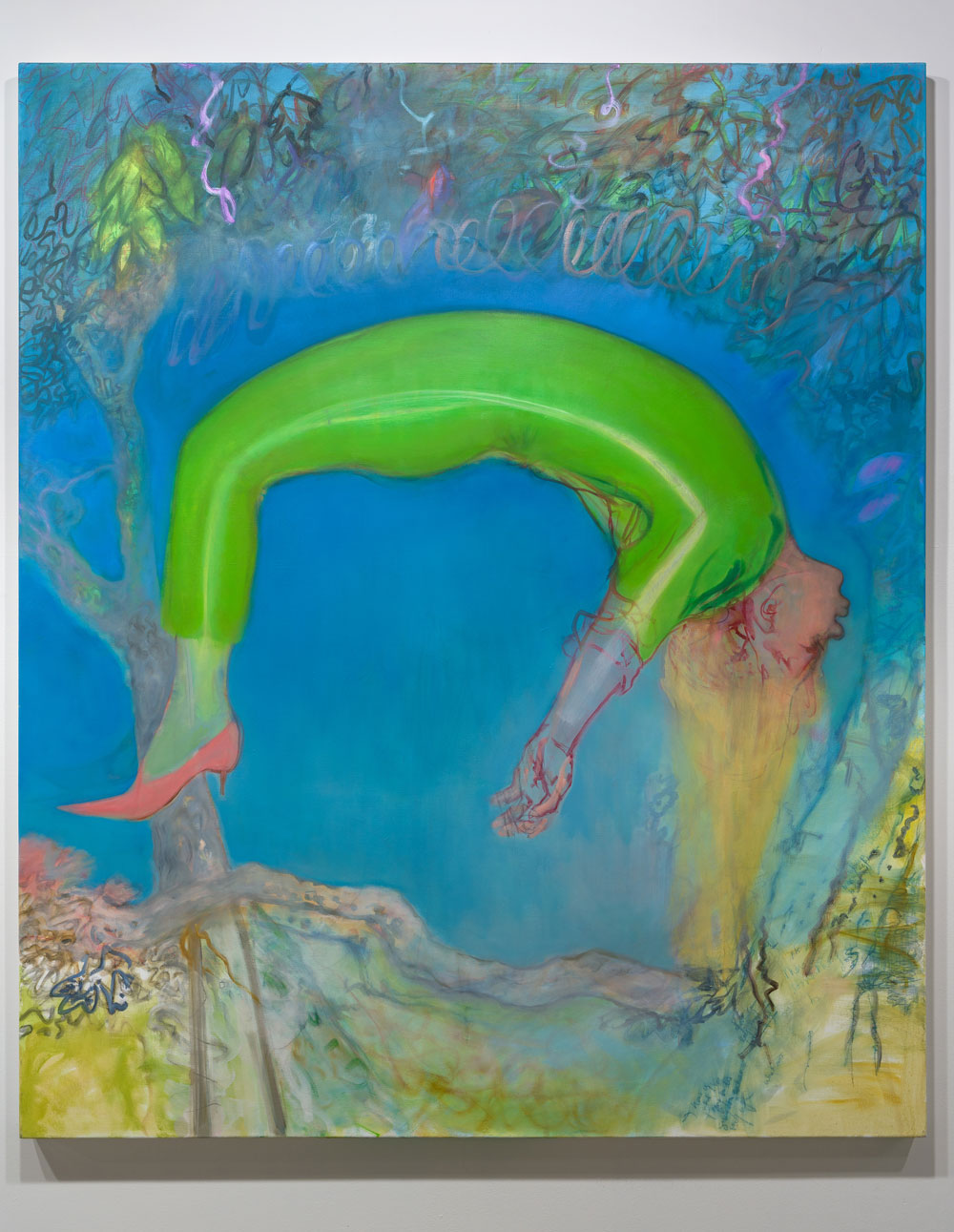

Eliza Griffiths, Because we care / Parce que nous nous soucions, 2016. Oil on canvas, 244 x 183 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Because we care / Parce que nous nous soucions, 2016. Oil on canvas, 244 x 183 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Chaos and Love in the Morning, 2016. Oil on canvas, 92 x 122 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Chaos and Love in the Morning, 2016. Oil on canvas, 92 x 122 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Bon secours / I have you, 2016. Oil on canvas, 244 x 183 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Bon secours / I have you, 2016. Oil on canvas, 244 x 183 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Levitation, 2016. Oil on canvas, 152 x 122 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Levitation, 2016. Oil on canvas, 152 x 122 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, “Actes D’Amour,” 2016. Installation view at ELLEPHANT Montreal. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, “Actes D’Amour,” 2016. Installation view at ELLEPHANT Montreal. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Storytelling, 2016. Oil on canvas, 122 x 152 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.

Eliza Griffiths, Storytelling, 2016. Oil on canvas, 122 x 152 cm. Copyright Eliza Griffiths and ELLEPHANT.