Situations are what they are and also what we bring to them. The industrial town of Dniprodzerzhynsk lies 400 kilometres from Kiev on a road so potholed that we travelled at snail speed for many stretches and, even so, blew a tire and had to change it after sundown by the light of Donald Weber’s iPhone. We were six hours into a nine-hour drive through what seemed like a single muddy field; dark, rich soil in this, the breadbasket of Europe, with the last of the winter snow lining the few gullies in shadow. On the horizon were rows of tall leafless trees; closer to us were occasional rivers and ponds surrounded by bulrushes where Ukrainians fish for carp. At the end of the 19th century, Canada’s Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton, looked to this part of Europe for that “stalwart peasant in a sheepskin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children”—immigrants of “good quality” to be settled in the startlingly similar topography of the Canadian Prairies.

Intermittently along the route, peasants stood bundled up in old coats, congregating in the labyrinthine roadside markets that appeared from time to time. We ate in one of these, later stopping at a bar where a few men were teetering in an unlit doorway. You could sense that beating up a foreigner might constitute decent entertainment for folk who, when they work at all, do so for long days and low wages. The absence of any real possibility of joy was stifling, though I was aware that it may have been my jet-lagged mood speaking. Vova, Weber’s fixer, sensed my trepidation and shrugged. “They’ve never had any fun,” he said before resuming the drive to Dniprodzerzhynsk, still a couple of hours down the road.

Dniprodzerzhynsk, a steel and chemicals factory town on the banks of the Dnieper, population a quarter of a million, is where Weber has been working off and on since a 2004 assignment as a news photographer found him in Kiev’s Independence Square during the Orange Revolution. Weber, whose high-school photography teacher urged him not to bother with the craft, trained as an architect and was working in Rem Koolhaas’s Rotterdam office when a friend lent him a camera. The feeling of it in his hands was a revelation. He turned to photojournalism, working for Newsweek, the Guardian, Stern and the New York Times, and was trying, without success, to take a photograph of the triumphant Viktor Yushchenko making an address to hundreds of thousands of people in Independence Square when Vova, standing behind Weber and at that time a stranger to him, came to his aid by clearing the space in front of him with a strong, steadying arm so that Weber was able to frame a clear shot. It was Vova who later accompanied Weber to Chernobyl (the site of his harrowing photo essay Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl, the work that made the Canadian’s reputation), and who first brought the Toronto-born and -raised photographer to Dniprodzerzhynsk, his own hometown. Time, in this eastern part of the country, has taken a rest; there has been the same sprouting of Orthodox churches that has occurred elsewhere in Ukraine since perestroika, and there are a few modest malls, tellingly empty, but otherwise the skin of the town is still Soviet in this markedly pro-Russian region. The steel factory is in the centre of town, the chemicals plant and others at the edge of it. On a residential street by the river, a Iosif Stalin Model 2 tank appears to be rolling up and over the stone plinth it is mounted on. Children play in its turret’s open hatches and slide along the cannon; around the pedestal a woman pushes her pram towards the birch-lined riverside path along which men idle next to their cars.

There is a lot of idling in Dniprodzerzhynsk—and, quite unwillingly, Weber and Vova have become a part of it. The work that Weber is doing here has been contingent upon the co-operation of a local police major named Igor. He is known locally as chort, the devil, and his unit as the “Third Reich.” It is Igor who is responsible for tending to the juvenile delinquents of Dniprodzerzhynsk and Igor who has let Weber photograph his police work, including his physically and psychologically brutal interrogations of suspects. Only now the major has become recalcitrant and the project has stalled. Weber, delayed for weeks, is at the end of his tether. He is tired of Ukraine, tired of Dniprodzerzhynsk, tired of the policeman who was previously helping him out. He has started to think about future projects, in particular about his next one, in Brazil, and is impatient to finish the series of photographs that is keeping him here.

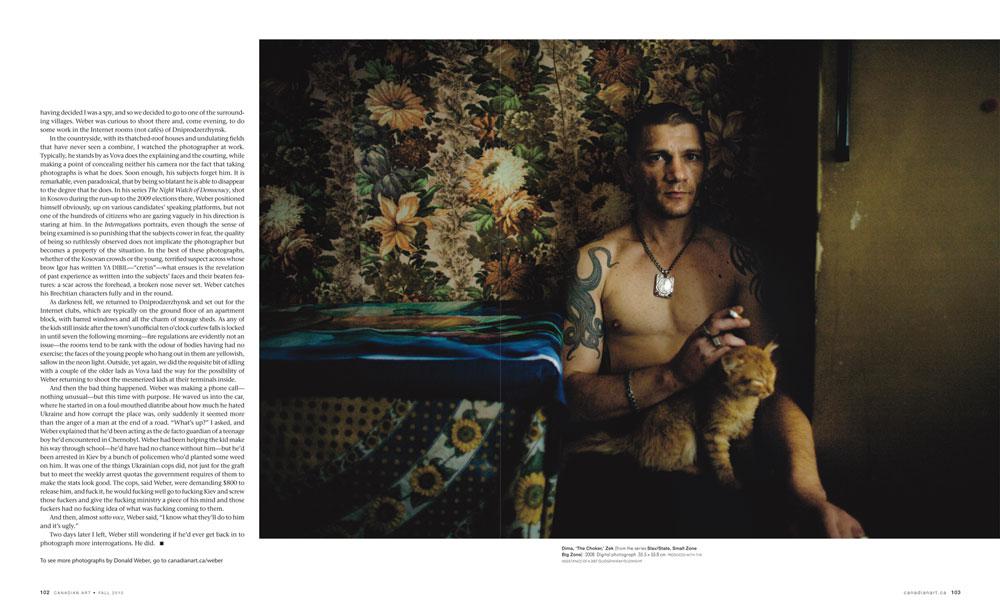

In his photographs, Weber does not show the violence of the police interrogations but concentrates on the suspects’ faces. He shoots them in close-up against the nondescript background of the police-station office Igor corners them in. The images he has shown me have the quality of a classical painting, and would sit comfortably in that austere middle space between a Piero della Francesca portrait and the Depression-era photography of Marion Post Wolcott or Dorothea Lange. But Weber is not finished, and he is pissed off that he is not finished and, most of all, he is pissed off with Igor. His mood is an impediment and untoward, because impatient and pissed off is never a good condition for an artist in the field to be in. The project may be about to end soon, whatever Weber intends for it. Igor, who has been promoted, seems to fear that providing Weber with access threatens to undo him in some way, or he might simply have lost interest.

And so Weber waits. Waits in a country that Transparency International’s 2009 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked alongside Zimbabwe and worse than Nigeria and Pakistan for public-sector corruption (Ukraine placed 146th out of 180 in the world—Canada ranked eighth). He waits in a small industrial town that was remarkable for not much at all until it found prosperity under the Soviet Union because Leonid Brezhnev, the General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1964 to 1982, who was born in Dniprodzerzhynsk, located chemical factories and a massive steel plant here; waits by the side of the road in Vova’s car for the call to come and for a meeting at which Igor actually shows. The car is Vova’s office. He pampers it. He depends on it. He would live in it, except that he adores his women and likes to sleep with them. The mistress, certainly. The first wife, no longer, though he stays with her a lot to get away from his second, pretty Julia, with whom he’s had a daughter. This is why the car feels so good.

Tonight we are headed to Julia’s because, at my prompting, we’d invited the reticent Igor out. I’d thought that if I engaged Igor in some suitably deferential interview, he might be convinced that he had a stake in Weber’s work again and get the project back on track. But when Vova called to see if he’d meet us, Igor declared he did not drink.

“He says that every morning,” said Vova, phlegmatically. “In the evening it will be different.”

And in the evening it was. The major, having agreed to dinner at Julia’s, was waiting for us to pick him up at the foot of the apartment block where he lived. Igor was in his mid-30s, had slick dark hair, was baby-faced and handsome. He wore a smart leather bomber jacket with a wide fur collar and smelled of a lot of cologne. He directed Vova first to Beer World, a small pavement kiosk, where the bartender dispensed the major’s favourite draft into a couple of plastic water bottles arranged in deep rows for the evening takeout trade. Then we were off to another kiosk that carried scores of brands of vodka, and pickles and sausages too; outside, two young moms were doing their own hanging about, guzzling in the dark, kids playing at their feet.

Julia made solyanka, a cross between Hungarian goulash and a more Levantine-style lemony soup that Ukrainians tend to serve tepid rather than hot, and the beer went quickly, the vodka too. The major was carrying a silver pistol in a black leather shoulder holster that was showily strapped over his beige turtleneck sweater. From him I learned to take a deep long sniff of a quarter-cut pickle after each slug of vodka, though I was concentrating far too hard on whatever might have been his next move to get drunk. Weber was wary too, but more used to it, as he was to the formal toasts made, with each round, to the glory of some moment from history—heralding the brave fathers of the Resistance, and so on. When it came Weber’s turn to raise a glass he mimicked the major’s portentous tones and praised him, in English, for the sacrifice of days spent beating the hell out of young offenders too small and weak and disenfranchised to ever fight back. “All hail the major’s bravery! You’re a sick evil sonofabitch! I drink to your absence of courage!” he exclaimed, his steady gaze fixed on the major, knowing that he understood nothing. There was a battle of wills going on. You could see in the major’s eyes that he thought the Canadian was a weakling and see that Weber, in turn, despised him, but, in the way of such contests, each needed the other and put up with it.

It was late, and the man who did not drink knocked back the last of the second bottle of vodka. The conversation turned to chanson, a sort of Ukrainian-Russian style of underworld balladeering akin to country and western. Chanson originated in the crumbling czarist regime, persisted during the Soviet gulag and still thrives among the lower and criminal classes in what is still effectively a prison society. In its deeply lugubrious Slavic view, the experience of living on earth is dank and awful and nothing much is expected of it and there is no expectation of salvation in any further realm. In other words, there is no suffering on earth for a better life somewhere else, there is only suffering—a message that brought to mind Svidrigailov’s words in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment: “We’re always thinking of eternity as an idea that cannot be understood, something immense. But why must it be? What if, instead of all this, you suddenly find just a little room there, something like a village bathhouse, grimy, and spiders in every corner, and that’s all eternity is.”

I was thinking this as Igor raised his voice and angrily told us how much he hated chanson, with its lack of musicality and its lousy lyrics, and how the crooks that sang chanson should stay in jail and he wasn’t going to sing songs romanticizing them—and then he drank some more and did.

The next day Weber and Vova and I drove about Dniprodzerzhynsk, hoping for the call to say Igor would play ball again. It did not materialize, and in its absence Weber was swearing at him with such vitriol that I wondered if the real problem was that our photographer was in so frustrated and dire a mood that he was getting no breaks, inviting bad things to happen. He’d let the singing detective get under his skin. He’d shot four interrogations so far but was convinced that he needed to shoot another 15 or 16 to complete the series. The interview ruse had backfired, Igor having decided I was a spy, and so we decided to go to one of the surrounding villages. Weber was curious to shoot there and, come evening, to do some work in the Internet rooms (not cafés) of Dniprodzerzhynsk.

In the countryside, with its thatched-roof houses and undulating fields that have never seen a combine, I watched the photographer at work. Typically, he stands by as Vova does the explaining and the courting, while making a point of concealing neither his camera nor the fact that taking photographs is what he does. Soon enough, his subjects forget him. It is remarkable, even paradoxical, that by being so blatant he is able to disappear to the degree that he does. In his series The Night Watch of Democracy, shot in Kosovo during the run-up to the 2009 elections there, Weber positioned himself obviously, up on various candidates’ speaking platforms, but not one of the hundreds of citizens who are gazing vaguely in his direction is staring at him. In the Interrogations portraits, even though the sense of being examined is so punishing that the subjects cower in fear, the quality of being so ruthlessly observed does not implicate the photographer but becomes a property of the situation. In the best of these photographs, whether of the Kosovan crowds or the young, terrified suspect across whose brow Igor has written YA DIBIL—“cretin”—what ensues is the revelation of past experience as written into the subjects’ faces and their beaten features: a scar across the forehead, a broken nose never set. Weber catches his Brechtian characters fully and in the round.

As darkness fell, we returned to Dniprodzerzhynsk and set out for the Internet clubs, which are typically on the ground floor of an apartment block, with barred windows and all the charm of storage sheds. As any of the kids still inside after the town’s unofficial ten o’clock curfew falls is locked in until seven the following morning—fire regulations are evidently not an issue—the rooms tend to be rank with the odour of bodies having had no exercise; the faces of the young people who hang out in them are yellowish, sallow in the neon light. Outside, yet again, we did the requisite bit of idling with a couple of the older lads as Vova laid the way for the possibility of Weber returning to shoot the mesmerized kids at their terminals inside.

And then the bad thing happened. Weber was making a phone call—nothing unusual—but this time with purpose. He waved us into the car, where he started in on a foul-mouthed diatribe about how much he hated Ukraine and how corrupt the place was, only suddenly it seemed more than the anger of a man at the end of a road. “What’s up?” I asked, and Weber explained that he’d been acting as the de facto guardian of a teenage boy he’d encountered in Chernobyl. Weber had been helping the kid make his way through school—he’d have had no chance without him—but he’d been arrested in Kiev by a bunch of policemen who’d planted some weed on him. It was one of the things Ukrainian cops did, not just for the graft but to meet the weekly arrest quotas the government requires of them to make the stats look good. The cops, said Weber, were demanding $800 to release him, and fuck it, he would fucking well go to fucking Kiev and screw those fuckers and give the fucking ministry a piece of his mind and those fuckers had no fucking idea of what was fucking coming to them.

And then, almost sotto voce, Weber said, “I know what they’ll do to him and it’s ugly.”

Two days later I left, Weber still wondering if he’d ever get back in to photograph more interrogations. He did.

To see more photographs by Donald Weber, go to canadianart.ca/weber

This is an article from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.