This conversation between co-thinkers Aylan Couchie, Raven Davis and Chief Lady Bird—all Indigenous artists working within different mediums, activist backgrounds, community contexts and career stages—is not meant to define cultural appropriation. There have already been countless conversations attempting to describe to a Canadian audience the specifics of cultural theft from Indigenous communities, and why it spiritually harms Indigenous peoples. As Aylan Couchie suggested during our discussion, “Google it!”

Instead, this roundtable is about the emotional labour surrounding fallout from the appropriation of Indigenous identities, spiritualities and visualities, most of which falls on the shoulders of Indigenous women, gender-variant and sexually diverse peoples. Appropriation frequently happens within and without Indigenous communities, and conversations addressing cultural theft should not be limited to the controversies that surround established artists like Jimmie Durham. Not all artists have access to the means, reach and resources to confront the thieving of Indigenous intellectual labour, the theft of their own work included. Still, out of responsibility to their Indigenous communities, artists and community organizers such as Couchie, Davis and Chief Lady Bird remain on the front lines of online activism around cultural appropriation.

Couchie, Davis and Chief Lady Bird consider themselves part of an informal digital network of activists, organizing their social media communities around Indigenous issues. The group recently made waves within Canadian art when they admonished the artist Amanda PL on social media for her appropriation of Norval Morrisseau’s distinctive Woodlands painting style. Couchie and Chief Lady Bird also took to media outlets to raise awareness about Amanda PL and Indigenous appropriation. After increased pressure from the public, Toronto’s Visions Gallery cancelled Amanda PL’s show. The media frenzy that ensued brought up several issues for Couchie, Davis and Chief Lady Bird—ranging from how to address lateral appropriation to having our intellectual and emotional labour appropriated by Indigenous men—all explored in this roundtable.

Lindsay Nixon: The Amanda PL controversy was an example of community-based activism addressing cultural appropriation, and showed transformation at the community level using social media as a tool for resistance.

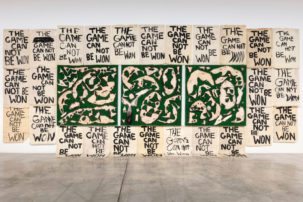

Aylan Couchie: We’re able to activate social media, as people not heard otherwise. Lindsay, you just had a conversation with Ryan Rice as part of the programming for Rice’s 2017 exhibition “raise a flag.” Rice described how artists used to have to organize by writing letters on typewriters. Now, social media helps our positioning and allows the message to get shared in real time.

Raven Davis: I can speak to the “typing age” because I’m the oldest here. [Laughs.] I was almost fired from my job in the early 1990s at Native Child and Family Services for using the fax machine to organize a protest. Nowadays, we can just use phones and social media.

LN: What do you guys think about people who say online activism isn’t real and that it doesn’t change anything?

AC: I get irritated when I see people who are critical of Indigenous women and two-spirit people being able to have a voice and a platform that wasn’t there before.

Chief Lady Bird: People don’t understand the work and emotional labour that goes into online activism. It becomes all-consuming and a full-time job. My phone wouldn’t stop going off for two weeks because a lot of the conversation about Amanda PL was on my Facebook posts. But people don’t see how online activism impacts us in our personal lives, behind the screen.

AC: At one point online or in an interview, I heard Amanda PL complain about the anger she’s received from the Indigenous community. But when Indigenous people engage in online activism concerning Indigenous issues in Canada, and particularly the cultural appropriation conversation, they experience a different but similarly intense backlash. Amanda PL was upset because she had all this backlash, but trolling and online bullying are regular occurrences for online Indigenous activists.

RD: We’re trying to be good people—role-model activists who are doing the right thing with as much integrity as possible—but it’s hard. It’s constant backlash and ignorance.

AC: I recently did a talk at OCAD University with Ryan Rice on the history of cultural appropriation. One of the questions we got from the students was, “I want to know why I’m just hearing about cultural appropriation now, at the end of four years at an arts institution.”

LN: Do you think that there is something about art that creates a culturally appropriative space? There’s this idea that art is a limitless space of images and icons that we can draw from. When we critique as Indigenous peoples, we’re told that it’s “just art” and that we shouldn’t take it so seriously.

CLB: I remember the first year of art school and how central European art was. For us as Indigenous students sitting in that class, we felt like our art wasn’t represented. But for non-Indigenous students, they were learning that Indigenous art isn’t important. Simultaneously we learned about Picasso and how he appropriated African masks to create the Cubist visualities he would become famous for.

So students are learning not only that appropriation is okay, but that some of Western art’s most famous artists appropriated from other cultures. By positioning Picasso as one of the greats in Westernized art history canons, non-Indigenous students end up internalizing and normalizing a culture of appropriation within contemporary art.

RD: We’re conditioning ourselves to focus all these issues on whiteness when we should also concentrate on lateral appropriation between our cultures. How do we have this conversation without whiteness being the central point?

At a conference I was at recently, there was a conversation about Mardi Gras Indians, something that’s received a lot of attention in Toronto at Carnival, with the bands who tried to show their solidarity with Indigenous peoples in Canada by wearing headdresses. Another conference presenter argued that the use of headdresses in Carnival isn’t an instance of appropriation because it’s not being used for monetary gain. I didn’t agree. It doesn’t matter that it’s not being sold or paid for. What matters is that it’s removing the voice from another person or culture, selecting specific aspects that seem more personally favourable than others, and manipulating or reinterpreting what’s been removed. It interrupts the ability to keep cultural knowledge and teachings sacred. We have a right and a responsibility to ensure the protection of Indigenous intellectual property.

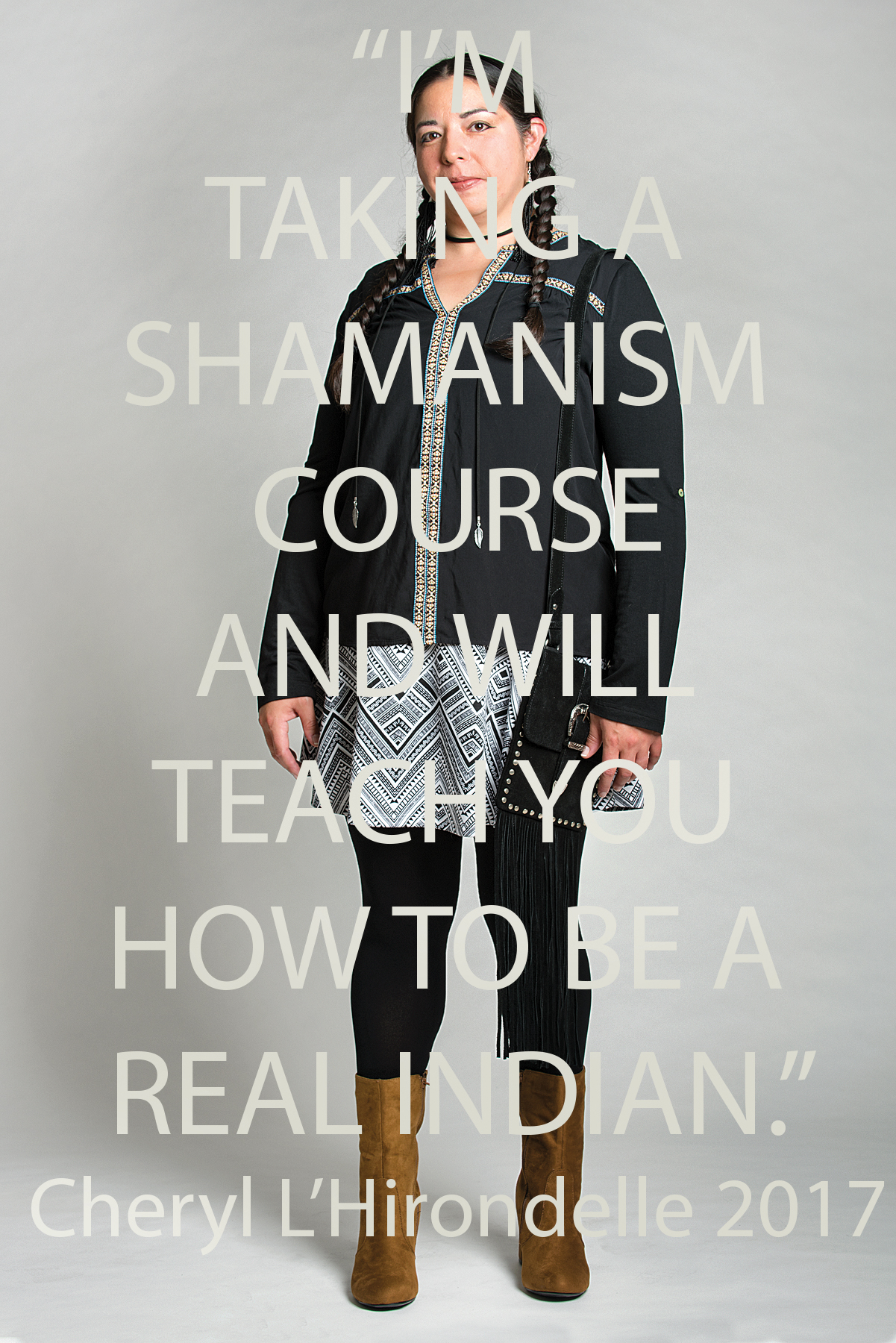

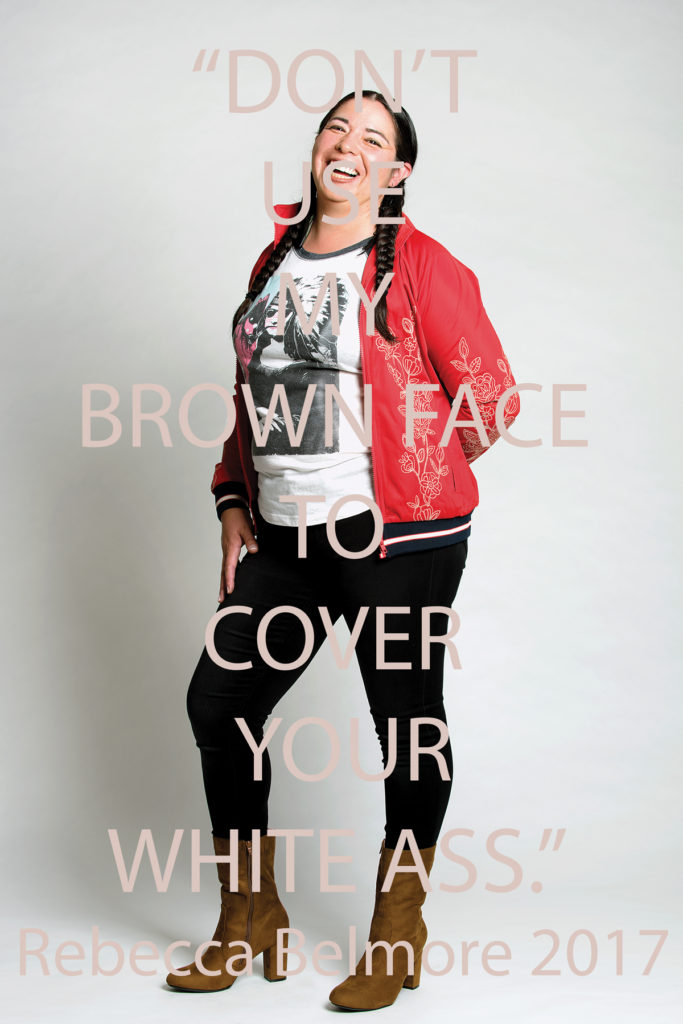

Ursula Johnson, Between My Body and Their Words, 2017. Contributors: Rebecca Belmore, Lori Blondeau, Cheryl L’Hirondelle and Shelley Niro. Photography. Commissioned by the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Raw Photography.

Ursula Johnson, Between My Body and Their Words, 2017. Contributors: Rebecca Belmore, Lori Blondeau, Cheryl L’Hirondelle and Shelley Niro. Photography. Commissioned by the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Raw Photography.

AC: I define cultural appropriation on a case-by-case basis. Carey Newman has been doing activism on the West Coast about Sue Coleman, who has made thousands of dollars on her paintings appropriating Northwest Coast style. I think there’s a lot of accidental appropriation, for sure. But there’s also appropriation done deliberately. Being a white-coded Anishinaabe woman, I have been careful because I have a responsibility to my community. I try to make sure my work is based on my knowledge and life experience.

RD: David Brooks would always do Woodlands-style artwork. He was an incredible Mi’kmaq man who had been in residential schools and who tragically passed away in 2014. When I first met him, I had the hardest time with his work. He was from the East Coast making money off of Woodlands-style art, which could be seen as an example of lateral appropriation because Brooks, as a Mi’kmaq, was appropriating from the style of Anishinaabe art. He generously offered to me that, being on the East Coast, Mi’kmaq people were the first ones hit by colonization. I remember him telling me the Mi’kmaq were the first assimilated and therefore don’t have a lot of representation of their art.

What can I say to that? What would it look like to focus on our people and organize protection of ceremony, culture and teachings? There will always be non-Indigenous people who want to attach themselves to our culture and ways of being because there are so many beautiful aspects that people are drawn to. When you yourself have lost your own pre–settler colonial culture and have morphed into the constructed “Canadian” identity, what exactly are you proud to share with your grandchildren? What grounds you?

LN: Do we want to talk about emotional labour and the responsibility to educate? You all must be burned out.

CLB: I’m totally burned out. If I’m always answering emails, then there’s no time for me to make the visualities that accompany the things we are trying to say. We have to figure out a way to segment and share our time. But we also have to nourish and heal ourselves too.

LN: Do you feel like you’ve been able to transform thought on appropriation positively?

AC: One of the positive things that came out of the conversation about appropriation was the activism that happened last spring around the “cultural appropriation prize.”

LN: That was unprecedented! The editor-in-chief of The Walrus ended up stepping down in part because of pressure from online activism. It helped to spark a lot of discussion about appropriation within Canadian publishing.

AC: Just this fall, the Canada Council for the Arts released a statement on cultural appropriation, saying that they were not going to be supporting artists who were culturally appropriative, in support of Indigenous communities. The Canada Council is an institution, but it’s one that maybe people are going to listen to. I don’t know if that would have happened if there hadn’t been this public conversation about appropriation. Jesse Wente, in particular, has been amazing at speaking out about appropriation in film and other areas for a while.

RD: Recently, when friends have asked me for advice on Indigenous issues and cannot afford to pay me consulting fees, I’ve started reminding them that my emotional labour is worth a donation to a local Indigenous organization. We have been teaching non-Indigenous people to think that our emotional labour isn’t valuable by not demanding compensation. That’s white supremacy in itself. Entitlement to our mind, body, spirit; our clothing, our language and our ways of being. Then, disengaging with us when it doesn’t benefit them.

We have many teachings on giving and receiving in our cultures. It’s not always about money, nor should it be, but how do we prevent giving to the point that we are being taken advantage of? We are not disposable and our knowledge is valuable.

LN: When you all engaged in online activism in response to Amanda PL, and the story started getting media attention, Indigenous men who weren’t involved in the initial wave of activism began taking interviews and tweeting about the issue. How do you feel about that?

AC: I’ve seen Indigenous men take thoughts from Facebook or Twitter, reword them and claim them as their own. The more people talking about it, the better. But at the same time, maybe back off a bit on taking that space and instead share the words of the original speaker.

CLB: I can feel my blood starting to boil a little bit. We do so much! And then, as often happens, they come in, say a few words, and everyone’s like, “You genius, you!” After all the work we’ve done.

My practice as a street artist began by working with men. When I’m in projects with men, I’m usually doing most of the work. Then the men are the ones who get the attention and take the credit, leaving out the contributions I’ve made. This is why women and two-spirit people have to support each other as much as possible.

This post is adapted from the article “Appropriation” in Canadian Art’s Spring 2018 issue, which is themed on “Dirty Words.”

Ursula Johnson, Between My Body and Their Words, 2017. Contributors: Rebecca Belmore, Lori Blondeau, Cheryl L'Hirondelle and Shelley Niro. Photography. Commissioned by the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Raw Photography.

Ursula Johnson, Between My Body and Their Words, 2017. Contributors: Rebecca Belmore, Lori Blondeau, Cheryl L'Hirondelle and Shelley Niro. Photography. Commissioned by the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Raw Photography.