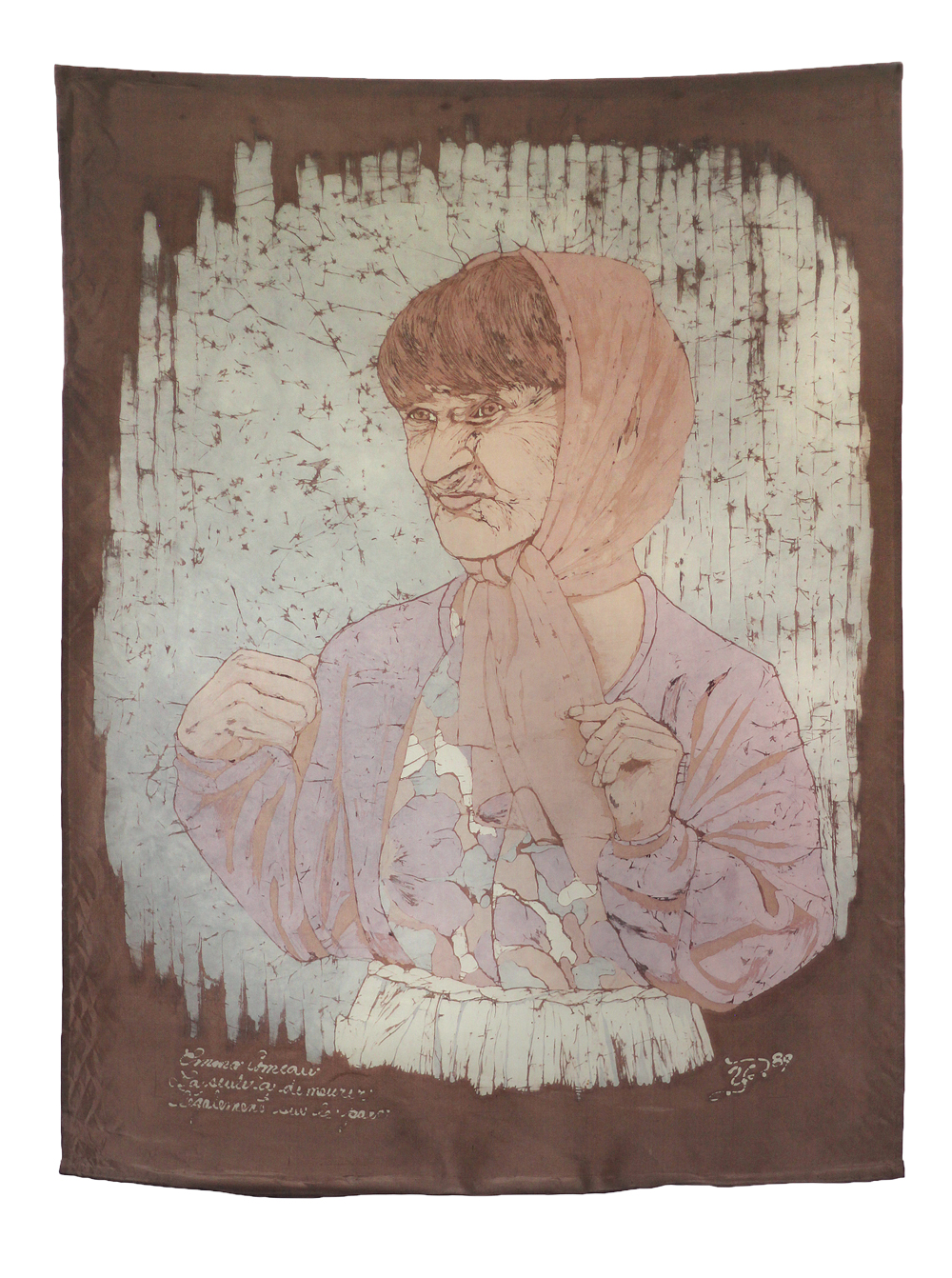

Yolande Desjardins, Emma Comeau, 1989. Batik on silk fabric, 101.6 x 77.5 cm. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Yolande Desjardins, Emma Comeau, 1989. Batik on silk fabric, 101.6 x 77.5 cm. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

In the prologue to his recent book, Kouchibouguac: Removal, Resistance and Remembrance at a Canadian National Park, historian Ronald Rudin recounts his surprise that no significant work of literature has ever been produced about the creation of the controversial park on New Brunswick’s east coast.

During the mid-1970s, the government-mandated removal of 260 families from their homes within the park’s boundaries would prove to be a focal point of resistance among Acadians. They saw only too clearly the parallel to the Great Upheaval of 1755, when their French-speaking Acadian ancestors were forcibly deported from the Atlantic provinces by the British.

Rudin ascribes the neglect by historians toward the Kouchibouguac saga to the fact that Acadian issues have largely been annexed to Quebec, or simply ignored by the rest of Canada. Fortunately, the Kouchibouguac story has refused to stay silent, for as Rudin highlights, Acadian musicians, poets, novelists, playwrights and visual artists have constantly engaged with the unfolding events, telling and retelling a story that remains headline news in Acadie almost 50 years later.

The first phase of land expropriations from Kouchibouguac began in 1969, with families from two of the seven communities situated within the future park leaving voluntarily in exchange for paltry compensation from the New Brunswick government.

But other communities resisted and organized: in 1972, fishermen who would lose access to the park’s waters staged an occupation of the park’s offices. Coming in the wake of the Université de Moncton protests of 1968, many young Acadians took up the Kouchibouguac cause, engaging with the events either on the park grounds or from the intellectual vantage point of the UdeM campus.

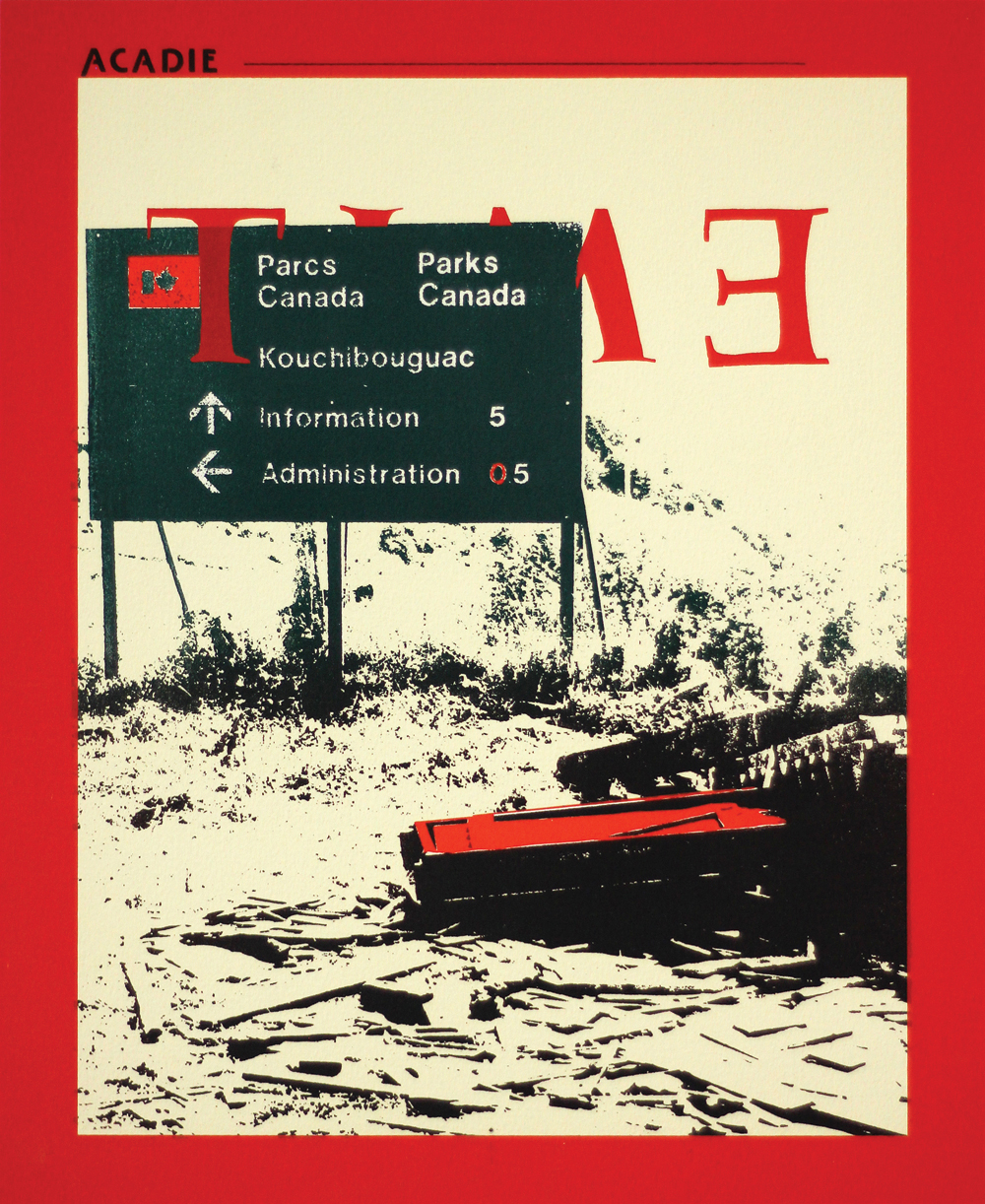

Pete Goguen, sans titre (Kouchibouguac), 1975. Screenprint on paper, 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Pete Goguen, sans titre (Kouchibouguac), 1975. Screenprint on paper, 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Pete Goguen (1950–98) was among these young Acadians. His photographic screenprint sans titre (Kouchibouguac) from the 1975 series Acadie Time, printed while he was still a student at the UdeM department of fine arts, appropriates the iconic red frame and typography of Time magazine in order to posit the events at Kouchibouguac as being of national importance.

Among the 10 known prints in the series, which address Acadian matters such as the Great Upheaval of 1755 and the shortlived Parti Acadien (a nationalist political party), sans titre (Kouchibouguac) is the most literal, showing a mangled red door in a pile of debris by a Parcs Canada sign. While some residents at Kouchibouguac took the painstaking route of relocating to lots just outside of park boundaries, many simply left their houses for demolition, leaving behind a highly symbolic image that would be appropriated by artists from all disciplines.

Among them, Claude Roussel stands out for returning to the subject of Kouchibouguac most often during the first decade of the saga, addressing key moments in the conflict as they made headline news. This socially and politically involved approach to making art was central to Roussel’s practice at the time of the resistance, and is best embodied by his series of resin sculptures that comment on contemporary Acadian struggles such as the fight for language equality and the unemployment crisis of the early ’70s.

One such work, Kouchibouguac, NB (The Great Uprooting), created in 1975, shows a large lobster claw bearing a New Brunswick coat of arms and grabbing at bits of debris, which include a doll found at the site of a former resident’s torn-down house. Its title references the Great Upheaval of 1755, when British officers forcefully removed Acadians from their homes and deported them toward unknown shores on both sides of the Atlantic. Before this analogy began gaining ground in the mid-’70s, the discussion about the expropriated families at Kouchibouguac had been centred on poor people rather than specifically on Acadians—but this was about to change.

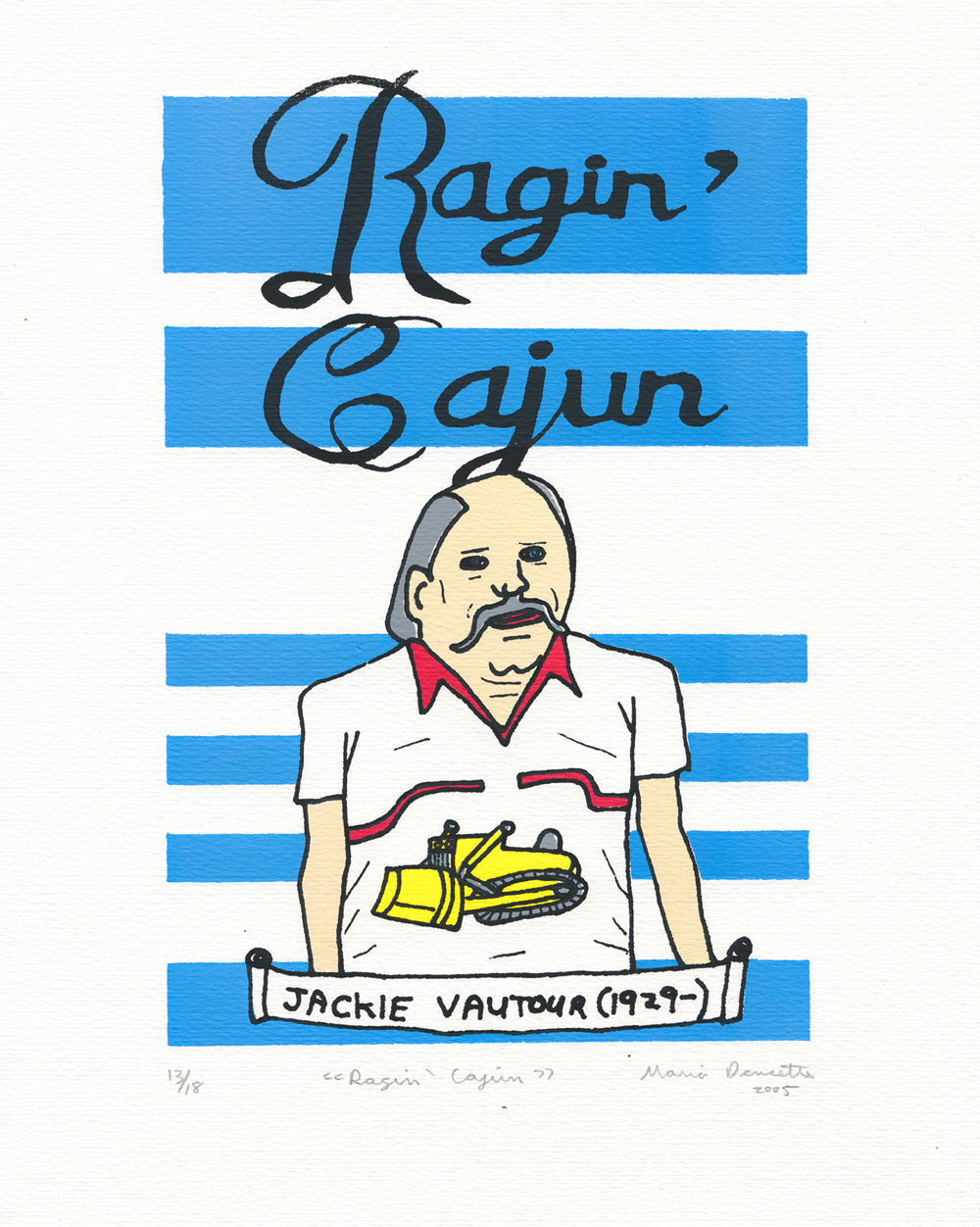

<img class=”img-responsive” src=” Mario Doucette, Ragin’ Cajun, 2005.

Mario Doucette, Ragin’ Cajun, 2005.

On November 5, 1976, news came out that Kouchibouguac’s most famous squatters, Jackie and Yvonne Vautour, had lost their home at the maw of a government bulldozer. By then, Jackie had become a controversial figure in the resistance movement, working with various groups for the cause of the expropriated families but often taking matters into his own hands—an approach that would land him in jail in 1973.

Although he wasn’t universally praised within the community, the destruction of his home struck a chord with many Acadians, including Roussel, who, in an act of solidarity, met with the resistance fighter following the demolition to gift him with the aforementioned resin sculpture. A black-and-white photograph taken that day shows a smiling Vautour holding the work of art outside of the Motel Habitant, where the New Brunswick government had temporarily placed the family before forcefully removing them again only months later.

When the Vautour family illegally moved back to the park in the late ’70s (where they remain today as squatters), acts of solidarity in the form of benefit concerts and demonstrations became the last major breaths of the communal resistance. The ’80s thus marked a transitional if not conclusive point in the Kouchibouguac saga, with the resistance movement slowly fading out while Vautour was elevated to an Acadian folk hero. The attention lavished on him, however, gave rise to feelings that the rest of the expropriated families had been forgotten in his shadow.

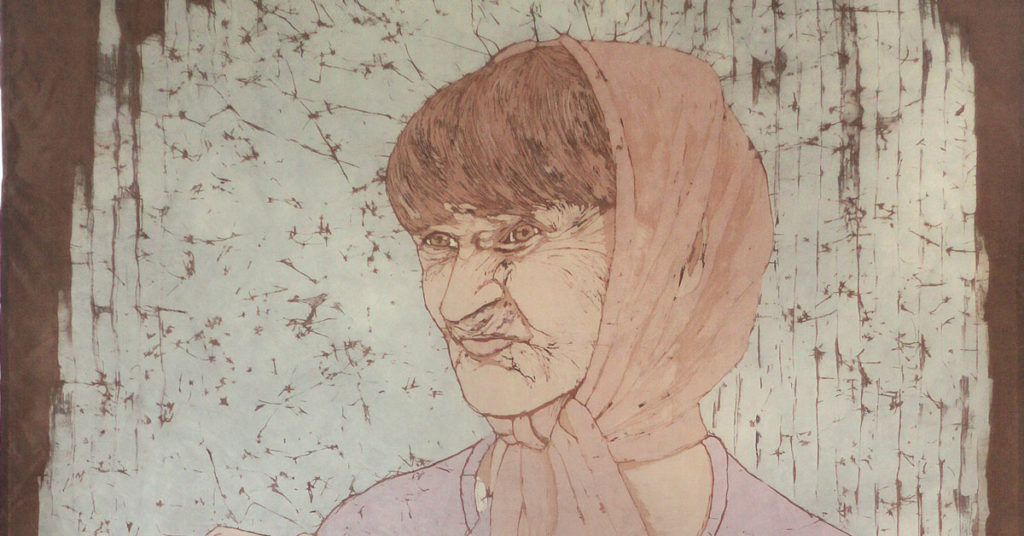

This was partly what motivated Yolande Desjardins to create a series of batik portraits in 1989 depicting elderly former residents of the park. Working from outtakes of the NFB film Kouchibouguac (1978), Desjardins set out to create a motorized kinetic sculpture that could animate six silk portraits into a single warping image. Despite plans to show the sculpture on three separate occasions, the project was eventually dropped, leaving the artist to complete only four portraits as standalone works.

Desjardins’s painterly approach to the batik technique of dyeing fabrics creates a crackled and weathered texture that highlights the difficult struggle that each subject has undertaken. This is most apparent in her near life-sized portrait of Emma Comeau, which showcases three times as many shades of dye than the other monochromatic works. Batik’s close ties to the hippie generation and ’60s counterculture in North America resonates within these political portraits, much like protest banners or political flags.

Claude Roussel, Jackie Vautour holding Kouchibouguac, NB (The Great Uprooting), 1976.

Claude Roussel, Jackie Vautour holding Kouchibouguac, NB (The Great Uprooting), 1976.

In the decades that followed, the Kouchibouguac story has lived primarily through the mythical figure of Jackie Vautour, who remains subject to artistic treatments to this day. In 1993, his central role in Zero° Celsius’s militant anthem Petitcodiac (Petty Coat Jack) brought his story to a new generation of Acadians in an emerging underground scene that included visual artist Mario Doucette.

Best known for his reinterpretations of Acadian colonial history, Mario Doucette has strayed from this central subject matter to include prominent 20th-century Acadian figures such as Louis J. Robichaud, Michel-Vital Blanchard and, of course, Jackie Vautour. All three were depicted in a 2005 screenprint portfolio called les rebels, an homage to Francophone militants. His portrait of the resistance fighter, titled Ragin’ Cajun (2004), shows a cartoon-styled Vautour wearing a bulldozer-branded polo shirt, underplaying the serious persona most often associated with the resistance leader. A floating banner bearing his name and date of birth makes it clear that the artist is commemorating an important figure—submitting him to the annals of history.

In the new millennium, Kouchibouguac and Jackie Vautour have become household names in Acadie, where they often return in the form of ceremonies, documentaries and, once again, headline news. Following an accusation of illegal fishing in park waters dating back to 1998, Jackie and Yvonne Vautour have remained in the media throughout the 2000s as they move back and forth between the provincial courts.

In this new battle, the resistance fighters have taken on a new discourse claiming Métis heritage, a claim that the provincial court of appeal officially refused to entertain in May 2017. As Jackie Vautour, now aged 88, prepares to bring his cause to the Supreme Court of Canada, Kouchibouguac and its expropriated families should remain in our collective thoughts as silent victims from an ongoing story that Acadian artists will no doubt keep deconstructing for many years to come.

This post is adapted from an article of the same title in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art. Its production has been generously supported by the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Yolande Desjardins, Emma Comeau (detail), 1989. Batik on silk fabric, 101.6 x 77.5 cm. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.

Yolande Desjardins, Emma Comeau (detail), 1989. Batik on silk fabric, 101.6 x 77.5 cm. Photo: Rémi Belliveau.