Photo-Journal reporter: “[Patsy Gallant] works just as well in English as she does in French and shares her time between English Canada and Québec.… It’s been said of her that she is English or anglophone.”

Patsy Gallant: “It is false…I am Québécoise of Acadian nationality.”

Okay, can we just pause for a second here and admire how swiftly 1970s “Canadian disco queen” Patsy Gallant throws a sparkly, diamond-encrusted bowl of fricot in the gears of this Montreal reporter’s naïveté? The scene is magnificent! The bowl flies across the dance floor, leaving a sarriette-speckled comet’s tail of golden broth trailing behind. For a brief moment, we (Acadians) truly believe that this will be transformative, but deep down we all know how this is going to end: the steel gears are going to cut right through the potatoes, the carrots and the all-important pâtes, no great lessons will be learned and 40 years later Acadians like me will keep being mislabelled because of the perceived cultural vagueness that comes with being Acadian.

For the purpose of this conversation, why don’t we name that vagueness Acadianness (insert sparkle emoji here).

Acadianness, to me, is a culturally specific experience that, although settler in origin, doesn’t always comply with the inherited colonial expectations of either French Quebec or English Canada. It has historically been met with confusion and disdain from onlookers on both sides of the French–English language binary. Whether it was British authorities deporting our politically “neutral” ancestors more than two centuries ago, or Québécois journalists shaming the pan-linguistic beauty of my own Chiac dialect today, Acadians always hear the same basic message on repeat: “Pick a side, kid.”

“When I say ‘lost,’ what I really mean is ‘lost in relation to the Acadian community.’ We, the very people who should be the safekeepers of this 20th-century pop-culture narrative, have lost sight of its main characters.”

This cultural glitch is at the heart of an experimental historiography project I’ve been working on called Hier semble si loin (recently shown at Montreal’s Galerie de l’UQAM), wherein I’ve taken it upon myself to piece together the missing chapters of a lost history of rock ’n’ roll music by Maritime Acadians before the mid-1970s. (For context, it’s in the mid-’70s that the New Brunswick band 1755 emerges as an all-encompassing Acadian group, performing original rock-inflected numbers such as “Maudite guerre.”) But the issue here isn’t so much that the music has been “lost”; after all, Acadian rock musicians were able to produce a wealth of 45-rpm discs and a handful of LPs that collectors have carefully catalogued and categorized over the years. No, the problem here has to do with the categories themselves (and the people who control them), because Acadians from the Maritimes, being mostly bilingual, have produced rock music in both “official” languages, which, over time, has fallen into the trappings of the aforementioned binary. In other words:

French rock = Quebec; English rock = Anglo Canada;

Nothing = Acadian

So when I say “lost,” what I really mean is “lost in relation to the Acadian community.” We, the very people who should be the safekeepers of this 20th-century pop-culture narrative, have lost sight of its main characters: those we raised, loved and cared for. The circumstances have made it so that we have no idea what our own community did with early rock ’n’ roll, and based on my research, this amounts to about 15 years of recorded output (1958–73) that’s been mislabelled and thus historically misappropriated by either the (French) Québécois rock or (English) Maritime rock paradigms.

(Enter Patsy Gallant, all sequins and rhinestones.)

Patsy is a good case study for this 15-year rock chronology because, although she is known primarily as a ’70s disco sensation, she also performed and recorded “yé-yé” (the umbrella term for the pop and rock genre popular primarily in France in the ’60s) with her family group The Gallant Sisters from the mid-1950s through to 1967, at which point she briefly moved to psychedelic and hard rock, her first ventures as a solo artist. Throughout this era, she performed in both languages, an ability that was no doubt a defining factor in her getting signed by Columbia Records circa 1972, when her albums began being released in both French and English versions (a trend that spans her first five solo albums).

Despite this great plurality (I haven’t even mentioned that she switched to funk and soul before disco, and that she opened for James Brown in Montreal and Toronto in 1974), Patsy Gallant remains Acadian, and proud of it. That’s why I get so excited when I read the 1977 Photo-Journal interview. When she replies that she’s not only Acadian, but also a proud tax-paying (my terminology) Québécoise (she’d been living in Montreal for almost 20 years by that time) what she’s really saying is: “Look buddy, your normative labels don’t define me—I got my own labels.” I don’t think that many Acadian rock musicians before her would have had the courage to put their cultural identity forward like the Canadian disco queen does here. Acadians were masking a lot more back then, be it out of insecurity (still an issue today), shame (to a lesser extent) or a desire to just fit in with the dominant mass cultures they saw on television (the media revolution of their generation). Thinking about it now, I feel that an international disco career would have been the sort of major chops needed to gain agency in a linguistically divided industry like mid-20th-century Canadian music. Otherwise you were just a small-town Acadian group from the Maritimes that had to sell records to either anglophone or Quebec-francophone audiences.

This resulted in a culture of adaptation where record labels (and the artists themselves) liberally played up either the Quebecness or the Angloness of their Acadian-origin groups in order to make the “product” more saleable to target audiences. This is often an extra hurdle for me in my research, because crucial information such as musician names and places of origin—telltale anchor points to the Acadian eye—have been fictionalized, exaggerated or obscured on the records themselves, or in other documentation. In other words, I can’t wholly blame amateur collectors for not seeing the complex identity politics that play into the Acadianness of these groups when, really, the artefacts don’t offer much to go on in the first place. But I have something to go on: my desire.

So why don’t we spend some time on the dance floor,

flip through this discography together and

give visibility to some of the more obscured identities

of the story? I even brought some fricot

for later—and no, it’s not chicken soup, it’s fricot.

(The needle drops, the disco ball glimmers.)

A vintage 45 of the 1959 tune “Looking for my Baby” by Acadian group Cliffy & Jerry.

A vintage 45 of the 1959 tune “Looking for my Baby” by Acadian group Cliffy & Jerry.

Cliffy and Jerry, “Looking For My Baby” (1959)

Quality Records, catalogue No. K1839, Toronto

Let’s set the table before we begin here.

Acadians currently live as a post-Acadie (the former French colony), post-expulsion populace. Their fragmented settlements are grouped only by a territorial fiction that is still called Acadie, and which is most often associated with the broader settler term, the Maritimes, but actually shares borders more closely with Mi’kma’ki, the traditional unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq (with a handful of communities crossing over into traditional unceded Wolastoqiyik territory, most notably the Madawaska region). This means that you’d be looking at very specific places when looking for Acadians on the map—Minto, New Brunswick, located in the predominantly anglophone Queens County, is not, in my mind, one of those places. So imagine my surprise when a woman named Doris calls me from Minto one day and starts talking to me in Acadian French about her cousins Cliffy Legere and Jerry Robichaud (turns out that Doris’s maiden name is Belliveau, like mine).

It honestly makes me laugh to think that Cliffy and Jerry are a Legere and a Robichaud—both super common Acadian names—because their records credit their original songs to the much more glitzy Cliffy Short and Jerry Banks! Of the three 45s they recorded in Toronto between 1958 and 1959, “Looking For My Baby” is by far my favourite. It’s an upbeat rockabilly bopper that stands out for the fact that the entire vocal melody is harmonized between the two singers—a signature style of the duo. It’s the kind of number that makes you want to throw a nickel in the jukebox and drink root beer floats.

Sophie José, “Robert” (circa late 1962, early 1963)

Series ABC, catalogue No. A-4509, Montreal

What do Sophie José, Tony Roman, Normand Fréchette and a host of other ’60s Montreal performers all have in common? None of them are Acadian, and all of them recorded with The Gallant Sisters. Originally from Campbellton, New Brunswick, the sisters, known more commonly as Les Soeurs Gallant, moved to Montreal at the turn of the ’60s in order to make it in the music business (which they did). Although they released three 45s as a group (I particularly like “Viens chez-moi,” produced with Les Disques Fontaine), the sisters made their biggest mark working as session vocalists, a title that was left uncredited on what is believed by some to be hundreds of recordings. Fortunately, their voices have a distinctive tone that can be identified by an accustomed ear, but the haphazard lottery of actually coming across one of these 45s makes the task of compiling a discography nearly impossible.

Sophie José’s “Robert” isn’t the most rocking song that I could have picked for the sisters (Tony Roman’s “Crier, Crier, Crier,” circa 1965, being one of note), but of the handful of uncredited recordings that I’ve been able to track down so far, it remains one of my favourites because it’s such a good example of made-in-Quebec female vocal pop from that era.

Jean Dularge, “D’après une chanson de Bob Dylan” (1967)

Les Disques Acadisco, catalogue No. A-100, Moncton

If you’ve never heard of Jean Dularge or of his music, it’s likely because of this (utterly fantastic) B-side from his one and only 45. Recorded in 1967, this proto-psychedelic marching-band poem should have been the first political Acadian pop song to use Chiac as a poetic device, but it was pulled at the very last minute due to a licensing issue. Only a handful of radio stations got their advance copies before the rest were destroyed a few days later, making this the rarest 45 by an Acadian artist. I got my copy directly from his former manager, a retired priest, who told me the very little that I know about this elusive singer.

Jean Dularge is (or was) originally from Cocagne, New Brunswick. He moved to Montreal in the mid-’60s hoping to become the first Acadian singer-songwriter, but when his big debut flopped, he returned home and became a lobster fisherman like his father. The irony in this conclusion is that his lyrics actually criticize Acadian clichés (like the lobster fisherman)!

Had he been able to release this record, the course of rock history may have been altered—maybe I wouldn’t even be writing this right now?

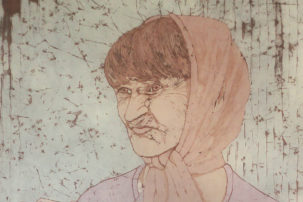

Members of the Acadian rock group Zylan, New Brunswick, ca. 1972.

Members of the Acadian rock group Zylan, New Brunswick, ca. 1972.

Zylan, “Ma Promesse,” from the album La Différence (1973)

Columbia Records, catalogue No. FS 90244, Montreal

Why don’t we close the night off with a slow jam? Well, okay, a hard-rock ballad by a nine-piece psychedelic funk band.

I actually get emotional when I listen to this song. I don’t know why. Maybe because it comes from such a miraculous moment in history, when three Acadian acts from New Brunswick—Patsy Gallant, Édith Butler and Zylan—all released debut albums in French on one of the most well-regarded labels in the world, Columbia Records. Based solely on that fact, Zylan’s music should be as beloved today as Patsy’s and Édith’s, but it’s not.

In many ways, Zylan simply fell victim to poor management. Just before the release of their debut album, Rainbows, Dreams and Fantasies, the group broke up following a contract dispute. Columbia then cut a deal with lead signers Hélène Bolduc (of Saint John) and Réal Pelletier (of Edmundston), the only francophone members of the group, saying (or so I imagine), “Give us a French version of Rainbows, Dreams and Fantasies, and we’ll release both versions.” This became La Différence, and when all was said and done, a smaller lineup of musicians was sent to Montreal with the express goal of supporting the album(s). Unfortunately, only months later, the group was schemed into a long-term gig in a bar and subsequently called it quits.

(As Zylan plays the last note, lights come on over the dance floor.)

In retrospect, it almost seems as though Columbia Records, aiming for Canadian-market domination, tried to simultaneously play up the Quebecness and Angloness of Zylan without realizing that it might weaken the very fabric of the group. This is probably what makes me sad when I listen to “Ma Promesse,” the heartbreak of capitalist expectations. But if I close my eyes and allow myself to get carried away by my own “rainbows, dreams and fantasies,” just for a moment, I can imagine a world where Columbia Records would have played up the Acadianness of La Différence and sold that to everyone, Acadians included.

Thankfully I don’t have to fantasize that much anymore because in the last 10 or so years, record labels have finally started realizing that Acadianness actually sells. Just look at Radio Radio, Lisa LeBlanc, Les Hay Babies and Les Hôtesses d’Hilaire: they’re all signed with record companies, they all write songs in their regional dialects and they all make a living playing to both French and English audiences all over North America and Europe.

So now that the dance has transitioned to the after party, let’s all celebrate together knowing that Acadian music, past and present, is alive and well. Oh, and help yourself to some Alpine in the fridge; I don’t drink it personally, but they printed the Acadian flag on the can during the last Acadian World Congress, and I got myself a case thinking that sometimes it’s just nice to have something to call your own.

This article originally appeared in print with the title “Acadian Rock ‘n’ Roll.”