Daphne Odjig has died.

The news came via social media on Saturday while I was at Awenda Provincial Park on Lake Huron, painting with a group of OCAD University students. The aspiring young artists had just held an informal exhibition of their day’s work when the word came through. The students’ paintings were displayed on picnic tables under a visitors shelter in an unabashed blaze of colour that Odjig would have heartily enjoyed and encouraged.

Odjig was a bold, risk-taking artist herself, always experimenting with media, technique and themes. And she was devoted to young artists, especially young Indigenous artists. She loved to hear about their emerging work, their successes, and their aspirations. It seemed fitting to learn of Odjig’s death under the trees near the shores of Lake Huron, for she was born near the lake on Manitoulin Island and spent her formative years near its waters. Fall leaves came tumbling down around us as the Internet filled up with messages from across the country. Hundreds of grateful Indigenous people now working in various capacities in the visual arts—in curatorial positions, in galleries, universities and cultural centres—were posting their memories of her generosity and bravery, and the influence she had had on their careers. An inspiration. That’s what Daphne was.

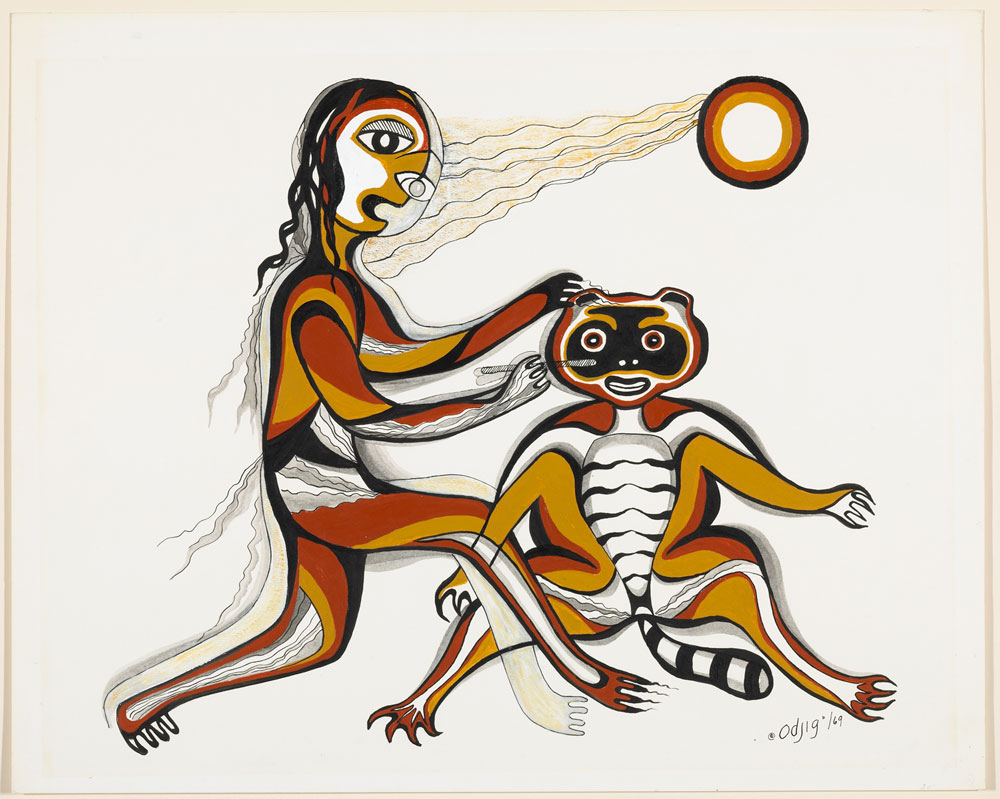

Daphne Odjig, Nanabush Giving the Racoon its Colours, 1969. Acrylic and graphite on ivory wove paper, 61.4 x 76.4 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Daphne Odjig, Nanabush Giving the Racoon its Colours, 1969. Acrylic and graphite on ivory wove paper, 61.4 x 76.4 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

I first met her in 2005 when I was working on Native Earth Performing Art’s production of Alanis King’s The Art Show, a musical play based on her life. Jani Lauzon was to play Daphne and I was to create the set and costumes. In preparation for her role and my production design, Jani and I travelled to BC to meet the great lady herself. How nervous we were as we walked down the corridor toward her apartment door. She was a legend to us.

Odjig was not only a painter. Her activism on behalf of Indigenous artists and their cultural production had been a formative influence during the 1960s and 70s, when Aboriginal communities were struggling to emerge from economic and social adversity. In 1971 she founded Odjig Indian Prints of Canada, a craft shop and small press in Winnipeg from which she distributed prints of her drawings and works by other Indigenous artists who were struggling to participate in the local art market.

Daphne Odjig, Roots, 1979. Acrylic on canvas (triptych), 1.52 x 1.21 m (each panel). Government of Ontario Art Collection, Archives of Ontario.

Daphne Odjig, Roots, 1979. Acrylic on canvas (triptych), 1.52 x 1.21 m (each panel). Government of Ontario Art Collection, Archives of Ontario.

By 1974 the craft shop had expanded and was renamed the New Warehouse Gallery. It was the first Aboriginal-owned art gallery in Canada and the birth place of a boisterous artists’ collective called Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. Comprised of Daphne Odjig, Alex Janvier, Jackson Beardy, Eddy Cobiness, Norval Morrisseau, Carl Ray and Joseph Sanchez, the collective was determined to challenge the barriers Indigenous artists faced in the Canadian art world establishment. In those days galleries and curators often saw Indigenous artwork as either exotic handicraft or cultural artefact more properly housed in a museum than in a public gallery as fine art. The audacious group organized innovative exhibitions in various venues across Canada and were soon popularly known as “The Indian Group of Seven.” Their ideas and influence were critical to the early development of contemporary Indigenous art and curatorial practice in Canada.

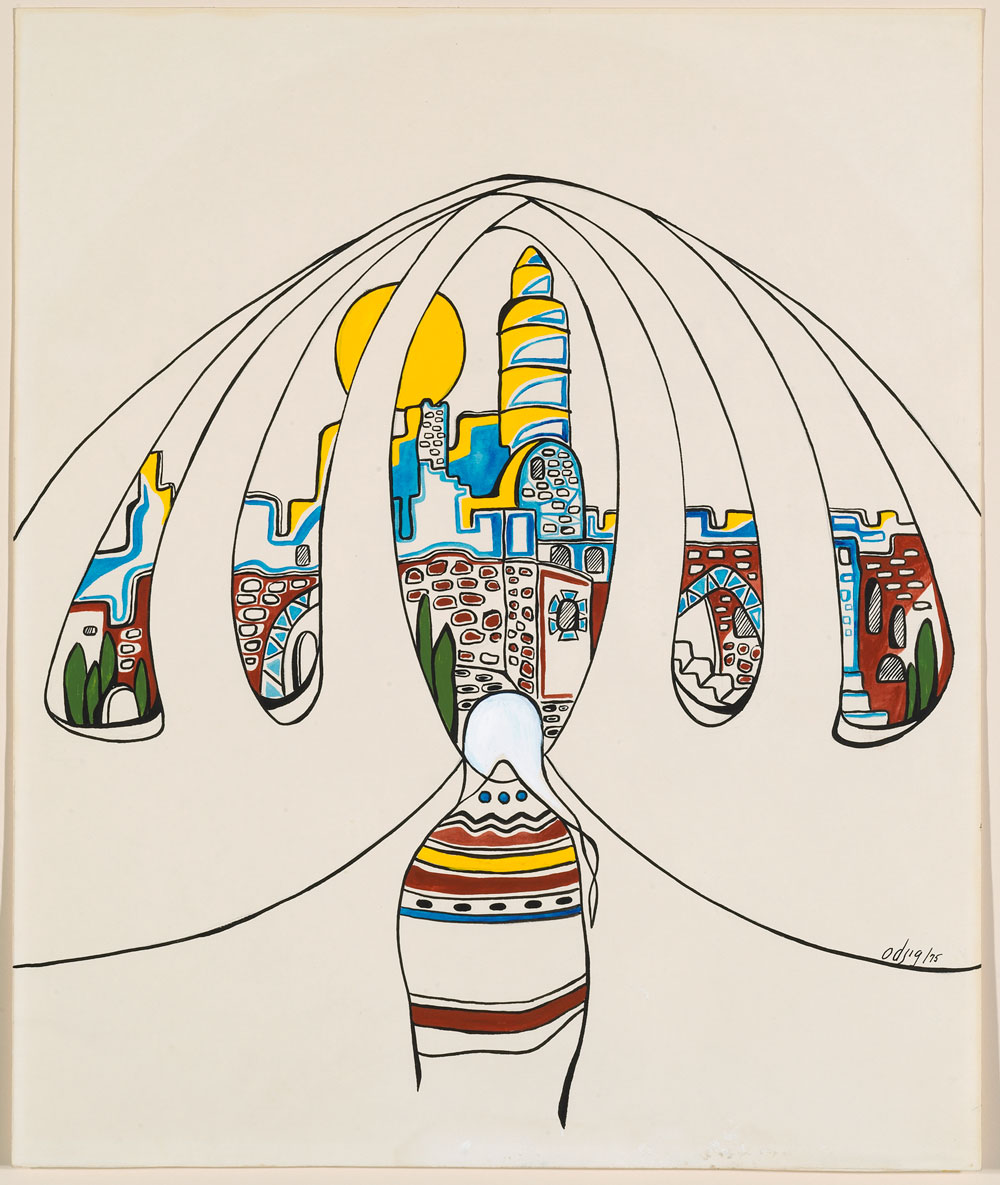

Daphne Odjig, Vision, 1975. Acrylic and graphite on ivory wove paper, 61 x 51 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Daphne Odjig, Vision, 1975. Acrylic and graphite on ivory wove paper, 61 x 51 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

At the same time, Odjig was making a name for herself as a painter of murals, history and legend paintings and narrative works that explored personal and collective memory and challenged national stereotypes of “Indian” life. A dynamic experimental painter, Odjig developed several distinct visual languages and graphic styles that she deployed across a number of thematic interests and concerns. In her seven-decade career she painted about family life and colonial history, produced complex abstractions derived from Anishinaabe legends and metaphysics, and created elegies in colour and form in response to the ecological urgencies of the forests of British Columbia, where she had lived since 1978.

In recognition of her contribution to the cultural life of this country, Odjig was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1986 and received a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2007. She held numerous honorary degrees from universities across Canada and exhibited her work in dozens of national and international solo and group exhibitions. She was a legend. Yet when Jani and I timidly knocked on her door in 2005 she opened it with a wide impish grin and a delighted chuckle and we quickly learned that her warmth and kindness were as generously bestowed and as powerfully expressed as her artistic gifts.

Daphne Odjig, Genocide No. 1, 1971. Acrylic on board, 61 x 76 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Daphne Odjig, Genocide No. 1, 1971. Acrylic on board, 61 x 76 cm. Collection National Gallery of Canada.

Daphne Odjig has died. She was an inspiration and role model for generations of Indigenous artists past, and for generations of Indigenous artists to come; an exemplar of tenacity, guts and grace for those of us who continue the work of defining and securing the place of Indigenous visual culture in the art world of Canada.

Baa ma pii miinwa Daphne, rest in peace.

Bonnie Devine is an Ojibway artist, curator and writer. She is currently Associate Professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences and Interdisciplinary Studies, and the Founding Chair of the Indigenous Visual Culture Program at OCAD University.

Daphne Odjig, From Mother Earth Flows the River of Life, 1973. Acrylic on canvas, 1.53 x 2.15 m. Collection Canadian Museum of History.

Daphne Odjig, From Mother Earth Flows the River of Life, 1973. Acrylic on canvas, 1.53 x 2.15 m. Collection Canadian Museum of History.