This week, Toronto will host a significant showing of Arab art at the Aga Khan Museum. Bringing together 24 works by 12 artists, “Home Ground” marks the first major exhibition of work from the Barjeel Art Foundation, one of the most significant art collections in the Middle East based in the United Arab Emirates. The foundation routinely lends work to exhibitions, and is now beginning to focus on creating institutional shows abroad. “We would love to share culture from the Middle East as much as possible,” said Suheyla Takesh, the foundation’s curator. “We always try to lend our works to institutions abroad, both in the Arab world and in the West and East.” With “Home Ground,” the Aga Khan Museum pips London’s Whitechapel Gallery to the post; a major exhibition of work from the Barjeel Art Foundation will be opening there later this fall.

While “Home Ground” offers a first for North American audiences, it represents only a small subsection of the collection’s holdings, which include some 1,200 pieces ranging from the early 20th century to present day. Yet even this sliver of the larger collection offers a diverse range: from internationally renowned artists, such as Mona Hatoum, to relative newcomers, like Charbel-joseph H. Boutros.

Boutros’s work reveals how the legacies of Conceptual art are influencing contemporary Arab work. His From Water to Water (2013) contains a series of typed instructions for the treatment of ice (a cycle of collecting, freezing and melting), while his installation Mixed Water, Lebanon, Israel presents a single glass of water on a shelf, flanked by two minimalist maps with pinpoints. The pinpoints mark the locations where the water was drawn—combined from two sources, Sohat and Eden. It’s a subtle, but poetic, gesture.

“Home Ground” also includes already established, but rarely shown artists—Asim Abu Shaqra, for one, is only occasionally exhibited in the Middle East. “He was born in Israel, studied in Tel Aviv and worked there. There are mobility issues with Israel and the surrounding countries,” said Takesh. “It’s difficult to get his work out of Israel, so he has almost never been shown in Arab countries. This is the first time we’re showing him in a group exhibition.”

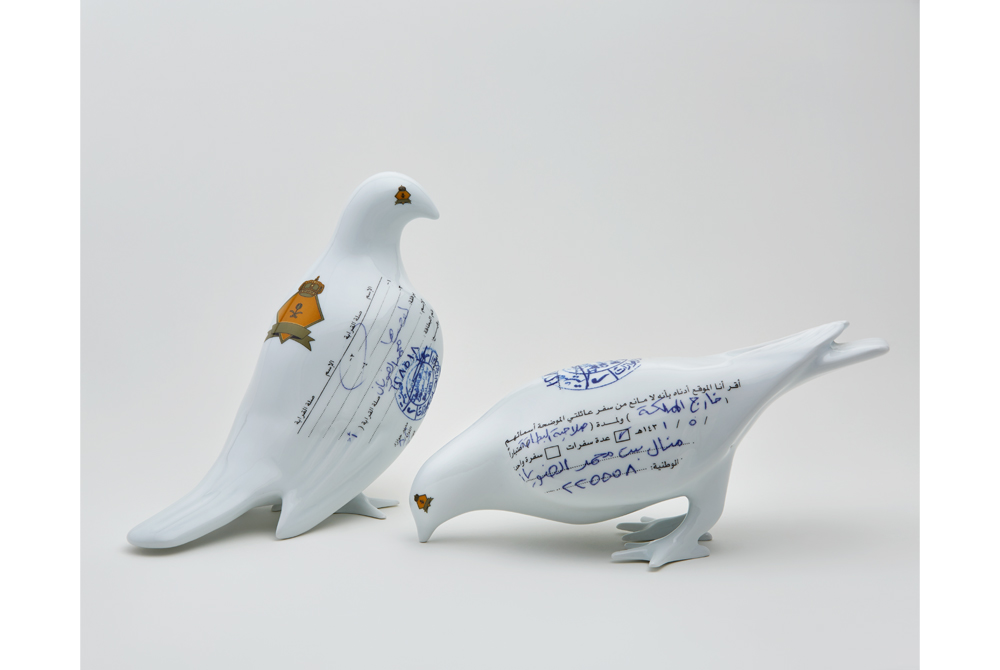

Strictures on movement, and its inverse—forced migration—form the general basis of the show. “It’s about defining homes and the idea of home, whether that’s linked to a physical, geographic location, or simply engineered,” said Takesh. “There’s a struggle inherent in these experiences—moving to a different place, crossing geopolitical barriers, gaining a sense of belonging.”

Perhaps no work in the show illustrates this more literally than Raafat Ishak’s Responses to an Immigration Request from One Hundred and Ninety-Four Governments (2006–09). A series of pastel, slightly abstract paintings on board, the work details Ishak’s rigorous process of inquiring with every recognized government in the world about citizenship. It’s bureaucratic minutia laid bare, made beautiful.

The peripatetic focus of the exhibition was part of the reasoning behind bringing “Home Ground” to Toronto, said Takesh. “Toronto is a very multicultural, multinational place. Our exhibition deals with themes of immigration and migration, looking at how artists reestablish and rebuild homes in completely new places. It’s something that the audience in Toronto, and in North America at large, will connect to.”

Canadians aren’t the only ones seeing new work in “Home Ground.” The opportunity to move the pieces into a different space, and context, has unveiled new registers of meaning to staff of the Barjeel Art Foundation, as well. “I was walking around the show with a colleague from the Aga Khan Musuem, who said that Boutros’s Mixed Water, Lebanon, Israel, for her, symbolized that we all drink from the same glass. It’s so exciting to hear these interpretations; I can’t wait to see how the general public reacts.”

“Home Ground” opens July 25, 2015, and runs until January 3, 2016.