With 1,500-plus photographers showing at more than 124 venues, there’s lots of options for viewing at the Contact Festival, the month-long celebration of photography that officially begins today in Toronto. Yesterday, our editor Richard Rhodes weighed in on the event; now, the rest of our editorial staffers offer their must-sees.

1) The Archive of Modern Conflict at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art

With offices and archives in London, England, Toronto and Beijing, and a collection of some four million photographs, cameras and related ephemera—including the recent record-breaking, $15-million-dollar acquisition of the Matthew R. Isenburg Collection of early photography—the Archive of Modern Conflict may well be the best little-known photography resource in the world.

“Collected Shadows” marks one of the first curatorial forays for the organization (a similar exhibition appeared at the Paris Photo art fair in 2012), which has been gathering, archiving and publishing photo materials from wide-ranging sources both amateur and professional for more than two decades.

The result—which I got a preview of—is awe-inspiring. For the exhibition, nearly 200 images drawn from the depths of the AMC collection are hung salon-style throughout the gallery. Assembled into thematic clusters designed to coax out associative links between the natural and the supernatural, it is at once an object lesson in the history of image-making and a poetic flight of fancy through the subjective curiosities and outright oddities of the camera eye.

In one set of images, the colour-saturated violence of a 1970 atomic-bomb detonation presides over pocket-sized black-and-white prints of flame-engulfed or burnt-out houses, vehicles and bodies. In another, composite images of urban streetscapes show alongside an early 20th-century photo of US warships docked at Guantanamo Bay and a panoramic view of the lunar surface. And in another set, pages from a German album of aerial views of the bombing of Rotterdam show with vintage black-and-white photos of Mexican pueblos, Navajo portraits and an 1899 telescopic print of Mars.

In an online interview, exhibition curator Timothy Prus calls the AMC a “collection of stories.” If anything, the historical parallels and visual coincidences brought together in “Collected Shadows” takes this one step further, calling into question the tenuous connections between fact and fiction that are often taken for granted. “If anything,” Prus says in the interview, “it makes everybody more skeptical about what they think history is when they see the primary source material and then realize you can’t trust primary source material because it’s all skewed.”—Bryne McLaughlin, managing editor

2) Erik Kessels at the Contact Gallery

In 2011, Eric Kessels downloaded all of the free and accessible images uploaded to the Internet in a single 24-hour period—maybe even a few of your own Flickr or Facebook images. Then he printed them all and installed them in the halls of the Foam photography museum in Amsterdam to create the 24 Hours in Photography, which blanketed doorways and floors like so many snowbanks or stacks of autumn leaves. Now, a portion of that one-million-photo project is coming to North America with a display of 350,000 images at the Contact Gallery. Though I’m sad we’re not getting the full effect, I look forward to visiting some friends at the Contact offices (adjacent to the gallery) and walking through at least a few mountains of memories.—Leah Sandals, online editor

3) “Light My Fire: Some Propositions about Portraits and Photography” at the Art Gallery of Ontario

The Art Gallery of Ontario’s assistant curator of photography, Sophie Hackett, opens the lid on the institution’s photography collection, which was initiated in the 1970s (that heyday for the appraisal of photography as an art form) with the acquisition of Arnold Newman’s portrait of Henry Moore. Since then, portraiture has become a defining aspect of the collection. This exhibition occurs in two parts: the first portion, “Light My Fire,” contains works of a more lyrical bent, by Robert Flaherty, Paul Graham and others, as well as works on “the idea of portraits as monuments in all senses” and “manifestations of the group portrait.” The second part opens this fall.—David Balzer, associate editor

4) Maryanne Casasanta at Toronto Image Works Gallery

Toronto-based artist Maryanne Casasanta’s playful photographs have a unique observational quality that stems from her sly interspersing of art with everyday life. Much of her work begins with creating small-scale interventions and in the production of fleeting sculpture–actions that she fixes through the act of photography. In this translation, Casasanta reflects on photography’s ability to imbue commonplace subjects with immediacy and importance.—Sam Cotter, editorial intern

5) Arthur S. Goss at the Ryerson Image Centre

The longer I live in Toronto, the more interested I am in seeing images of the city during an earlier era. My navel-gazing fix (or part of it) for this month will be secured at this exhibition featuring the work of Arthur S. Goss, Toronto’s official photographer from 1911 to 1940. Much of the pleasure I take in these kinds of photographs has to do with mentally comparing how similar or different these intersections were from the way they are now—and taking comfort, perhaps, that streetcar-track construction might have seemed as annoyingly slow 100 years ago as it does to me today.–LS

6) David Hlynsky at De Luca Fine Art Gallery

Hlynsky, a Canadian-American photographer with ties to Toronto, took his Hasselblad to Communist Europe during its twilight years, 1986 to 1990. In the series on view at De Luca, it might seem as if he purposely avoided any dramatic or newsworthy activity—and indeed, people altogether. Instead, shop windows, signs and other inanimate banalities are his subjects here. Bringing to mind Andrei Ujica’s epic documentary The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu and the paper-recreation photos of Thomas Demand, Hlynsky’s work is mesmerizing proof that ideology can often be found in the humblest, kitschiest things.—DB

7) Jackson Klie and Michelle O’Byrne at Beaver Hall Gallery

Jackson Klie and Michelle O’Byrne’s recent works seem a natural pairing; both artists investigate expanded ideas of photography, employing collage, video and sculptural installation to address medium-specific concerns and issues of representation. Much of the work in this exhibition is based on instructional materials for aspiring photographers in 1950s, 60s and 70s, and the artists work to expose pervasive ideologies that seem pedagogically engrained in the medium. Klie and O’Byrne will be giving artist talks on May 11. (I also will be speaking on the exhibition’s “New Modes of Image-Making” panel on May 18.)—SC

8) Robyn Cumming at Erin Stump Projects

I’ve been a fan of Cumming’s since seeing her Lady Things series of 2008, which for me was a compelling mix of feminine nightmare and feminist slapstick. (Talk about a genre mashup!) This new show promises to look at faces and physiques in general while retaining her knack for the ridiculous and the object-based.The exhibition is called “Bad Teeth,” which bodes well again for a few nightmares—hopefully, enjoyable ones.—LS

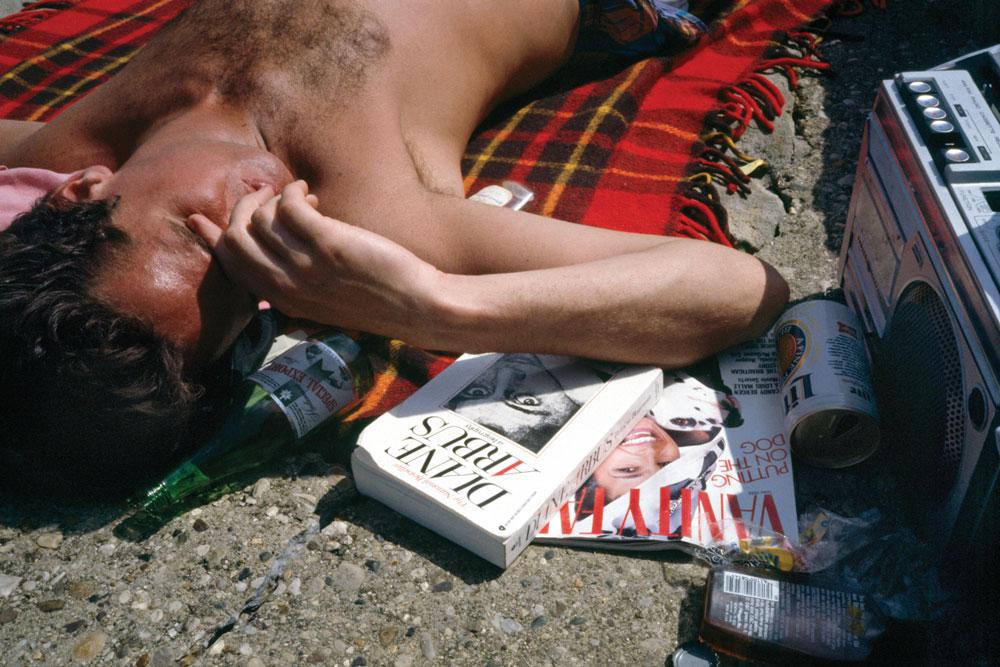

9) Doug Ischar at Gallery 44 and Vtape

The luscious, sexy photographs that comprise Doug Ischar’s 1985 series Marginal Waters—portraits of young gay men sunning themselves in various states of undress at Chicago’s Belmont Rocks—will now, inevitably, be seen through a glass darkly (in the words of the Contact program guide, through “AIDS and reaction”—presumably, homophobic violence). But the images themselves, on view at Gallery 44, remain a joy to behold. (Contrast their rough-and-ready rocks-and-grass environs with the chic beaches of Tom Bianchi’s Fire Island Polaroids of around the same period, recently published as a book.) Ischar’s newer installation and film work will also be on view at Vtape.—DB

10) Dan Epstein at IMA Gallery

Law & Order, real-world style, promises to be on view in young Toronto photographer Dan Epstein’s exhibition “Defenders.” The show features portraits of Canadian and American defense lawyers in Detroit, New York and Toronto. And the depictions aren’t just photographic—they also include interviews about the criminal justice system and its failures. An intriguing proposition for documentary study, and a chance to glimpse a set of oft-unexamined (and genuinely, rather than merely theatrically, haggard) personalities.—LS

11) Mark Peckmezian at Harbourfront Centre

This Toronto-based portrait photographer is turning heads. His commercial work was recently featured in the New Yorker and Toronto Life. And locals may in fact recognize him for an unturned head: Peckmezian was production photographer for Kazik Radwanski’s much-discussed indie film Tower, and his Derek—a clean, muted shot from behind actor Derek Bogart, his bald spot on beautiful display—was used evocatively in the film’s posters and ad campaign.—DB

12) Jason Evans at the Art Gallery of Ontario

Though UK artist and 2012 Grange Prize runner-up Jason Evans is perhaps best known, via his blog The Daily Nice, for images that capture a millennial version of visual pleasure, his artist-in-residence project at the AGO obliquely takes on issues of institutional critique. For it, Evans has photographed staff in the AGO’s conservation, curatorial, design, development, education, facilities, finance, kitchen, media education, protection services, and visitor services departments. Pleasure still enters in the fact that Evans asked each employee to pose in a manner that reflects a favourite leisure activity. Though I’m unsure about the posing strategy, I’m excited to see some behind-the-scenes players put front and centre.—LS

This article was corrected on May 2, 2013. The original copy suggested that the fall-opening portion of “Light My Fire” was not part of Contact and that it would include a section on portraits as monuments. It also suggested that David Hlynsky was American, not Canadian-American, and that his photography in Eastern Europe and the surrounding region focused exclusively on non-figurative work; and it suggested that Doug Ischar’s work was solely on view at Gallery 44. Canadian Art apologizes for these errors.

Doug Ischar MW 1 1985/2009 (Image 1/20)

Doug Ischar MW 1 1985/2009 (Image 1/20)