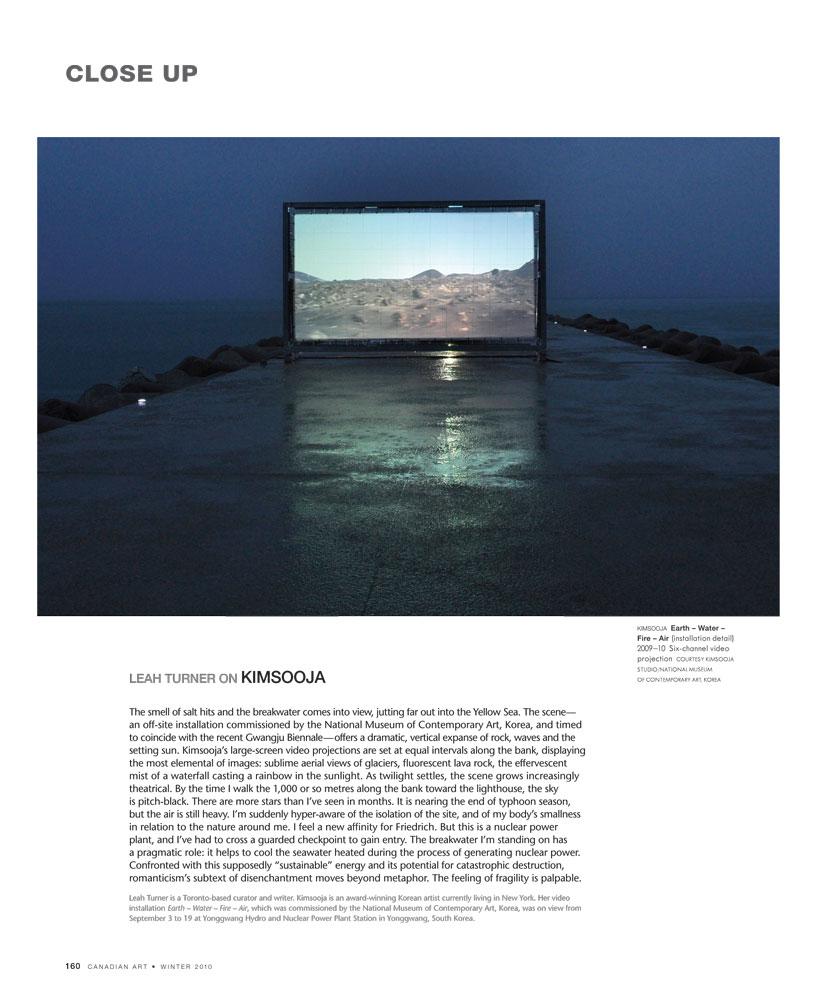

The smell of salt hits and the breakwater comes into view, jutting far out into the Yellow Sea. The scene—an off-site installation commissioned by the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea, and timed to coincide with the recent Gwangju Biennale—offers a dramatic, vertical expanse of rock, waves and the etting sun. Kimsooja’s large-screen video projections are set at equal intervals along the bank, displaying the most elemental of images: sublime aerial views of glaciers, fluorescent lava rock, the effervescent mist of a waterfall casting a rainbow in the sunlight. As twilight settles, the scene grows increasingly theatrical. By the time I walk the 1,000 or so metres along the bank toward the lighthouse, the sky is pitch-black. There are more stars than I’ve seen in months. It is nearing the end of typhoon season, but the air is still heavy. I’m suddenly hyper-aware of the isolation of the site, and of my body’s smallness in relation to the nature around me. I feel a new affinity for Friedrich. But this is a nuclear power plant, and I’ve had to cross a guarded checkpoint to gain entry. The breakwater I’m standing on has a pragmatic role: it helps to cool the seawater heated during the process of generating nuclear power. Confronted with this supposedly “sustainable” energy and its potential for catastrophic destruction, romanticism’s subtext of disenchantment moves beyond metaphor. The feeling of fragility is palpable.

Leah Turner is a Toronto-based curator and writer. Kimsooja is an award-winning Korean artist currently living in New York. Her video installation Earth – Water – Fire – Air, which was commissioned by the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea, was on view from September 3 to 19 at Yonggwang Hydro and Nuclear Power Plant Station in Yonggwang, South Korea.

This is an article from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Winter 2010/11 issue of Canadian Art