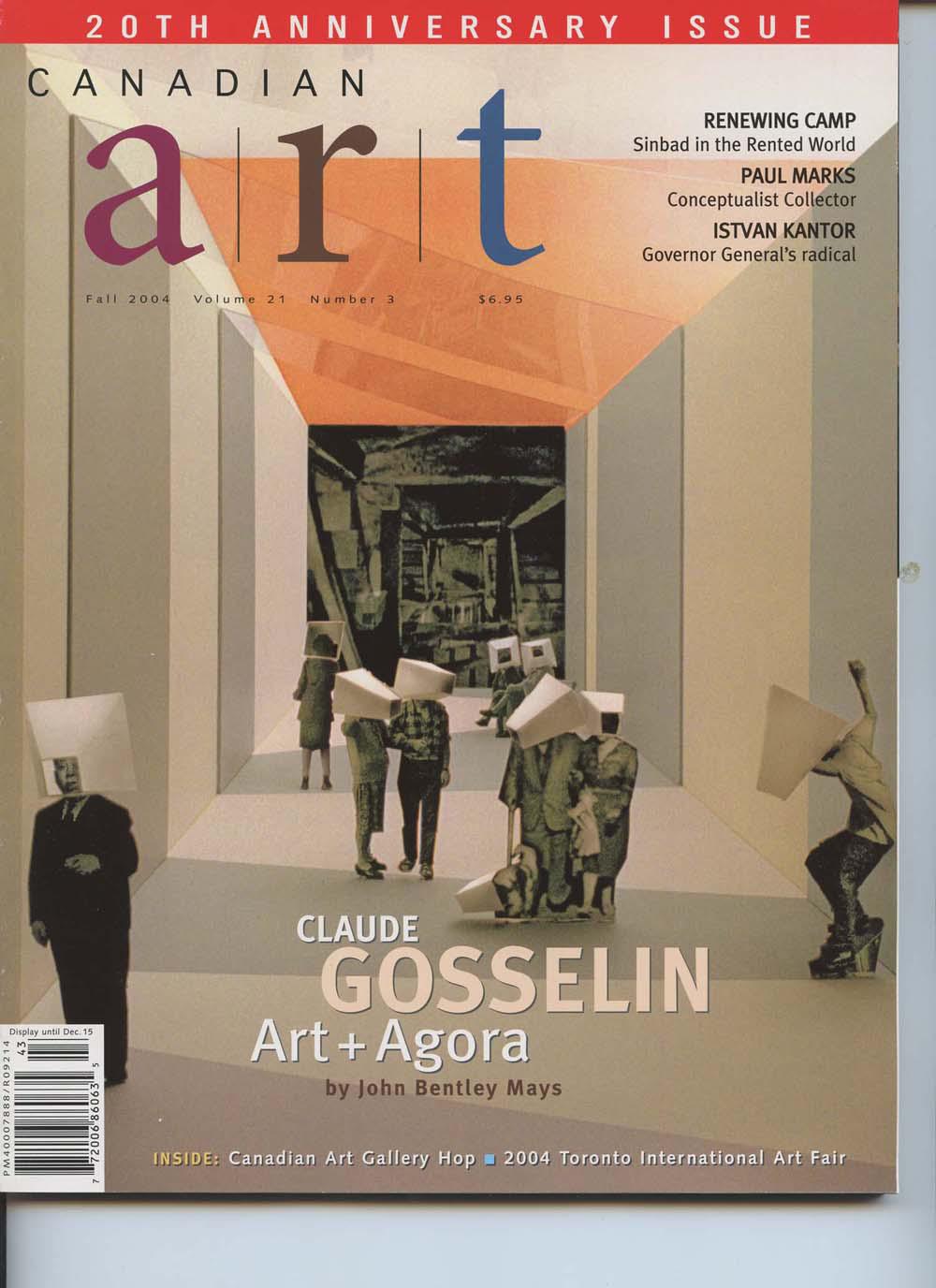

Claude Gosselin is Quebec’s top curator of international contemporary art, and one of the most extravagantly energetic, talented independents at work in the Canadian art world. With the September opening of the fourth Biennale de Montréal, Gosselin’s Centre international d’art contemporain de Montréal (CIAC) celebrates 20 years in the business of bringing intelligent, provocative international and Canadian art to Quebec. Over those two decades, Gosselin has raised and spent millions of dollars on his single-minded pursuit of contemporary art that matters, and on his project of finding and showing Montreal what’s engaging in visual culture today.

I caught up with him at CIAC’s quietly humming office in downtown Montreal in late June. Gosselin was openly smarting about being passed over for the position of director of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, a job he deeply wanted and actively pursued. (The appointment of former Power Plant director Marc Mayer had just been announced.) “Our generation is not allowed to get the only job in Montreal for us. And now we are too old, so it’s finished for us,” said Gosselin (who is 60, but looks 20 years younger). “They’ve hired someone from outside the family.”

But, if understandably miffed by this institutional snub, Gosselin was hardly in the mood to sulk—especially with so much work yet to be done on the biennale. The day we met, he was, as usual, both all over the administrative map—tidying up schedules and programs, issuing press releases, doing the bureaucratic heavy lifting that comes with every large, complex show—and remorselessly focused on the cultural theme of this autumn’s biennale. The $1.2-million exhibition, scheduled to be on show from September 24 through October 31, is unlike anything CIAC has done before. For one thing, it’s not going to be about art, at least not as most museums show it and many people know it.

“For each biennale, I gave myself a new challenge,” Gosselin told me. “The last one was about drawing—small works, and much intimacy. This biennale will be completely different, a mix of art, architecture and design as a way to talk about the public domain.” While reluctant to give away surprises, the artistic director made it clear that the show will address large issues in contemporary urbanism, leading the imagination of visitors beyond neighbourhood fix-ups to a sense of the city as performative space. “It’s about the airport, the underground, public squares, large commercial shopping malls, because this is where people are, where you create culture. What’s important in the biennale is the feeling of a whole, not segments. It’s a big program. We won’t offer a lot of solutions.”

On offer, however, will be a small panoply of public projects designed to raise questions about our uses and abuses of urban space. On the loading dock of the former Gazette building on rue Saint-Antoine, British architect Will Alsop is creating an impromptu gallery of canvas equipped with paste tables and paint pots. In the place where newspapers were once dispatched to the Montreal public, visitors are asked to leave their mark as another intervention of the social into an otherwise marginal, transitional zone. (According to Gosselin, downtown Montreal’s quite satisfactory laneways are under attack from urban planners inclined to do some unnecessary tidying up.) Multidisciplinary artist Didier Fiuza Faustino, who lives in Lisbon and Paris, is putting a puzzling little structure in the midst of a yet-to-be-named public space, while an installation by Dutch urbanist Adriaan Geuze at Place des Arts will contest the cultural centre’s commercialization and architectural stodginess.

Though Gosselin has never been a political activist or ideologue, this biennale’s concern with public space and social architecture has recognizable roots in his personal history.

His long march to this fourth Biennale de Montréal began with studies in art history at the Université de Montréal and the newly-founded Université du Québec à Montréal beginning in the late 1960s. It was during this era of seething cultural and intellectual ferment in Quebec—and everywhere else in the world—that Gosselin found himself among intelligent, intensely curious friends who shared his interest in contemporary culture and his get-busy entrepreneurial flair. In the 30-odd years since the days of passionate talk and discovery that launched Gosselin on his creative path, he and the other members of his circle—Parachute editor Chantal Pontbriand, curators and art dealers France Morin and René Blouin, journalist Normand Thériault and others—have made indelible contributions to current knowledge and appreciation of contemporary culture.

“We were very grounded in the history of art,” Gosselin recalls, “and we were wondering: are we going to provide one more scholar of the Renaissance, or are we going to work on what’s going on here? There was something here we should be proud of, and we were aware of what was going on elsewhere. But we were always more entrepreneurs than thinkers. We were committed to doing things. Every day, even now, we are thinking. We have to grab what’s going on for a magazine or an exhibition.”

While Gosselin very much likes being his own boss, he has, like most other impresarios of contemporary art, done time inside Canadian cultural institutions. For three years in the early 1980s, he was head of exhibitions at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, where he organized shows of works by Robert Filliou, Dick Higgins, Michael Morris and other advanced artists and art movements (such as Fluxus) of the time.

“There was an excess of exhibitions, an opening every three weeks. You never had time to make a show significant to the city.” Fed up, Gosselin left the Musée and took on the organization of a large display of art, film, video and photography for “Québec 84,” a summer-long nautical and cultural fête celebrating the arrival of Jacques Cartier on these shores 450 years earlier. Gosselin founded his non-profit Centre international d’art contemporain de Montréal as the organizational tool for bringing off this show of art.

“I was put in charge of a big event, much larger than what you find in museums. I had to hire 60 people in a month for a show on the theme of water and wind, because that’s what brought Cartier here. In Montreal, people are still dreaming about Expo 67 and the Olympics in 1976. For me, it was ‘Québec 84’! The event was so big, and involved so many people and so much money. It was an experience you won’t get in everyday life.”

Then “Québec 84” was over, and he was back in Montreal. “I thought: mon Dieu! What am I going to do now? But these were the first years of the festivals—jazz, theatre, dance. So I wondered: how come we don’t have a festival for visual art in Montreal? We had artists, space for shows. So I hired René Blouin and Normand Thériault as curators and, in 1985, we did the first ‘Les Cent jours d’art contemporain de Montréal’—a deliberate recollection of the 100 days of Documenta. We picked 30 top Canadian artists and framed the show around the idea of installation art in Canada.” The highly praised and praiseworthy 1985 show, titled “Aurora Borealis,” featured works by Jocelyne Alloucherie, Noel Harding, Vera Frenkel, General Idea, Tom Dean, Raymond Gervais, Betty Goodwin and Irene Whittome, among others.

The annual “Cent jours” event ran for the next 11 years, except for 1988. In 1998, CIAC’s main project was reborn as a biennial affair. “Biennales were popping up everywhere. The biennale brings you to a network of cities, and there’s a certain aura attached. Also, having a biennale gave me a year between each event to think about the programs, to put Montreal on the network and to think about government funding, which was becoming more and more specific. You could get money to attract tourism, to hire people, to develop new publics, to do special programs and outreach. But it’s a funny thing—I could get money for promotion, but not more money for the artistic component of the project. Why have money for publicity with nothing to publicize? It has to go together.”

After more than 20 years of pulling together money and dealing with artists, Gosselin believes he has done a good job at both. Hundreds of thousands of people have seen his shows, according to his own quite reasonable estimates. CIAC’s HTML site is racking up 20,000 hits a month. “People know about ‘100 Days of Contemporary Art.’ We gave the artists the quality of respect they should expect. We gave the public high-quality activities. A certain public that never goes to museums discovered contemporary art through ‘100 Days’ and the biennales. That was quite something to do, without a permanent venue or staff.”

The public is never far from Gosselin’s conversation, whether the topic is marketing or aesthetics. “Public art was the beginning of my thinking. What is public art today? It is no longer the kind of sculpture that you drop in a corner of the city. Public art has to be in its surroundings, taking care of what’s going on in that place, in that corner, with those people at that square. It has to be part of the pavement, part of the walls—something other than a trophy. From public art in the city, you go very quickly to the ideas of urbanism, public design, places and architecture.”

Inspiration also came from what Gosselin feels is a takeover of Montreal’s famous festival culture by commercial interests. “How can you maintain places for the public without turning them over to the use of private enterprise? You bring people to those squares for festivals, and what do they look at? Publicity for burgers. And the Gap. Large public billboards. The architecture turns into a frame for the billboards.”

The flip side of this intensive use of public places in Montreal is the desolation that follows special events—a factor, Gosselin believes, not being given proper acknowledgement in Montreal’s current rush to build yet more places des spectacles. “What happens to those huge open squares when there’s no festival? They are wind corridors, with no trees because trees would hide the screen for the film festival, with no light poles because light distracts attention from the stage. You bring together 250,000 people three nights a year. Then what?”

It’s a question that may lie outside somebody’s strict definition of art’s proper province. But for Gosselin, the problem of keeping our cities humane, safe and alive is something that the performative, narrative, urbane and urban art of the present day can fruitfully address. “I see the biennale as something different from what a museum aims to do, and these works are different from what has been proposed as public art. The public is needed to animate these works, which are not only decorative objects in the city, but objects that live with people in the city, that can be transformed. We’re not focusing on a segment of the population on the edge. We want to open the eyes of the public.”

From the Fall 2004 issue of Canadian Art.