That Newfoundland painter Christopher Pratt is a Canadian artist of genuine importance and real distinction is scarcely ever, I think, disputed. What has not been examined closely enough, however, is the true source of that importance, his actual meaning as a painter. Despite the considerable amount of critical attention paid to him over the years (most of it respectful to a degree just short of idolatry), Pratt’s work continues to be regarded—rather muzzily—as the work of a painterly Platonist, a visionary with X-ray eyes for the reality that somehow lies beneath the sham of particularity.

For a quarter of a century now, Pratt’s spare pellucid meditations on the messages suspended within evacuated rooms, the translucent precision of the painted light defining his clapboard walls, the mute eloquence of his serene seas, have come together to form what most viewers and critics see as a world of idealized forms. The force of these images lies in their apparent ability to lift us from the banalities of the everyday into the grandeur of generality.

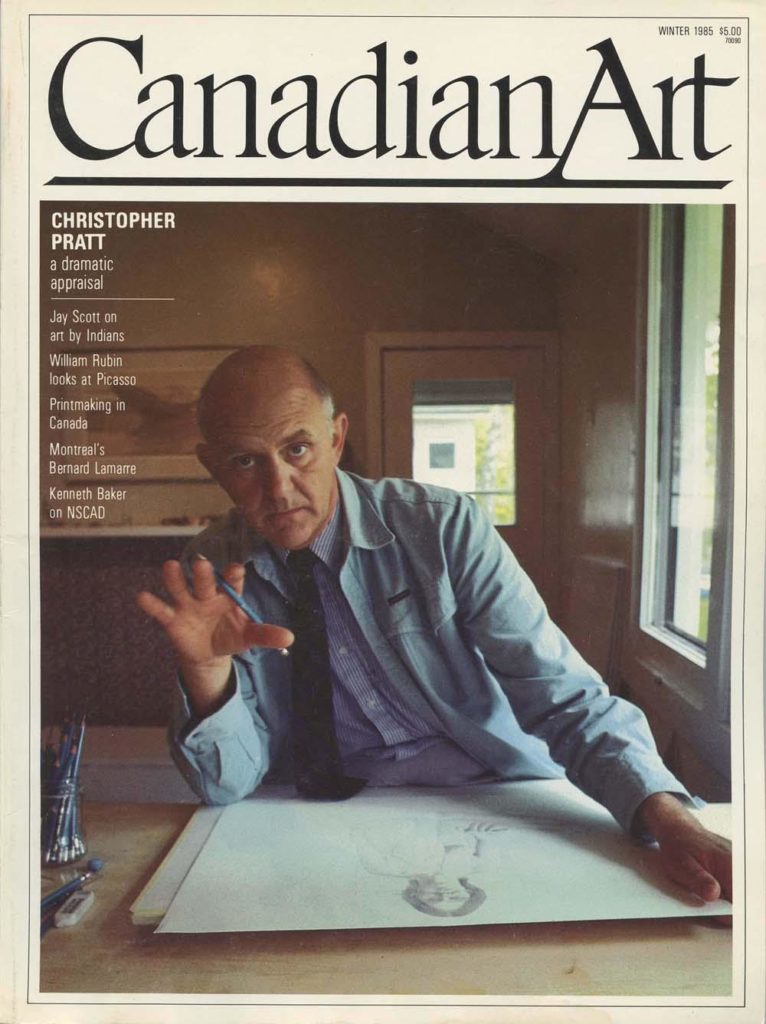

So begins the Winter 1985 cover story of Canadian Art. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.