Canadian-art artifacts can turn up in the most interesting and unexpected of ways.

During his photo research for Peter Goddard’s story on the 1960s Spadina Avenue scene in Toronto—forthcoming in the Summer 2014 issue of Canadian Art—managing editor Bryne McLaughlin got in touch with painter Gordon Rayner’s widow, writer Katharyn Rayner. Katharyn lives on Toronto’s Dupont Avenue, in the house she and Gordon shared before his death in 2010. His studio remains in the back, where a Polish-newspaper printing press used to be. It is a jumble of work and ephemera—a treasure trove of little-seen Rayners and of various photos and documents from throughout his life and career.

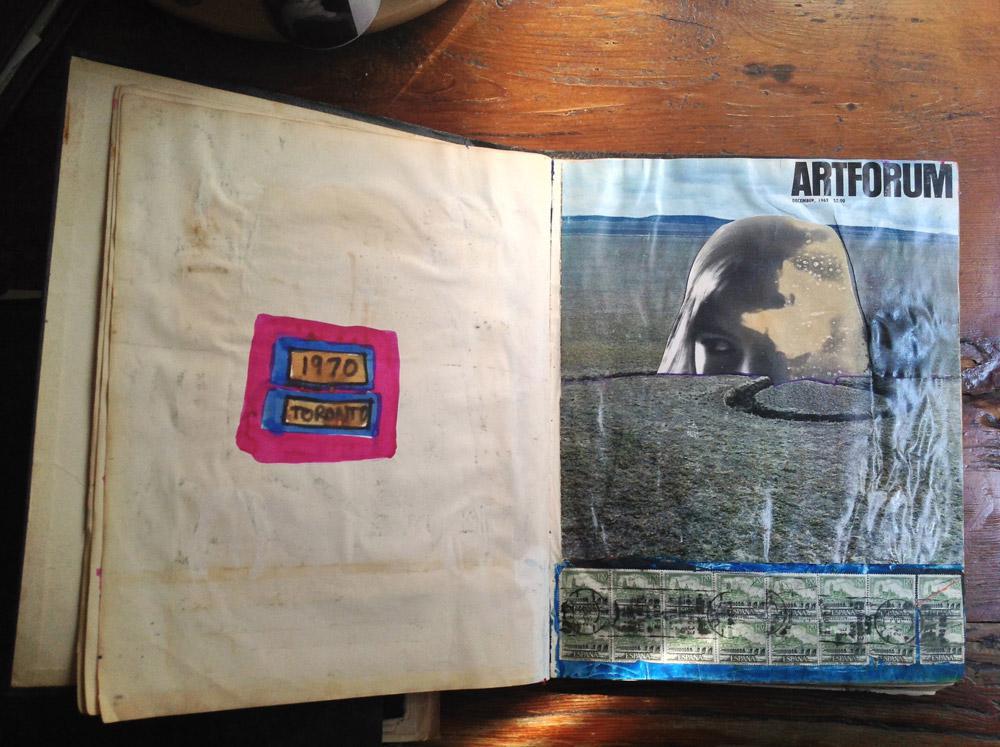

Katharyn told McLaughlin about Charlie’s Books, a series of collaborative scrapbooks Gordon made with friends and colleagues—mainly Robert Markle and Graham Coughtry—at a cabin in Magnetawan township in Ontario. Gordon nicknamed the books after the cabin’s owner, ex–Navy Seabee Charlie Clifton, who had known Gordon since he was a boy, and invited him to use the cabin whenever he wanted—which he did, to hunt, drink, eat and make art with an eclectic assortment of friends and lovers.

McLaughlin then viewed the 1972 NFB documentary Cowboy and Indian, directed by Don Owen, which contains a sequence in Gordon’s then-studio on Spadina of him flipping through one of Charlie’s Books. Intrigued, and with encouragement from Katharyn, McLaughlin visited Gordon’s studio in May 2014 with associate editor David Balzer to document one of the books.

The editors chose the earliest book Katharyn has. “I have about 10 books,” she says. “I’m saying ‘I think’ because there’s other stuff piled up in the studio that pertains to Gordon, but some of it is just clippings and magazines. Because of their fragility, I haven’t gone through all of [Charlie’s Books]. I want to do it with an archivist.

“When he moved from his studio on Spadina, Gordon left a bunch of boxes in the basement that I don’t think he ever went through. Now I’ve gone through almost all of them. He would fret occasionally: ‘Where are Charlie’s Books? They must be somewhere in the basement. I’d really like to see them again.’ So I was aware of them and that’s why I was so overjoyed when I found them. They were very important to him, not just for the memories and the fellowship, but because he thought the work in there was important and should be saved.”

Fifteen images from the book, which has only been seen by a handful of people—and has never been exhibited—are viewable by clicking on the Photos icon above.

For a complete view of this Charlie’s Book, including an extended introduction by Katharyn Rayner, please download our Summer 2014 tablet edition, available June 16 at appstore.com/canadianart.

A spread from one of the Charlie's Books created by Gordon Rayner and fellow Toronto artists, including Robert Markle and Graham Coughtry, beginning in 1969. (Image 1/15)

A spread from one of the Charlie's Books created by Gordon Rayner and fellow Toronto artists, including Robert Markle and Graham Coughtry, beginning in 1969. (Image 1/15)