For the past 18 years, Vancouver artist Carol Sawyer has been leading a double life. Namely, she’s been researching, documenting and otherwise channelling the work and life of the early 20th-century Canadian artist Natalie Brettschneider—in large part, she says, to combat the shortage of information about interdisciplinary women artists of the early 20th century. The latest iteration of Sawyer’s multimedia performance project Some Documents from the Life of Natalie Brettschneider opens this week at Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa. Here, Sawyer details some rare finds from the Brettschneider archive, and explains that while the real person that she has based her alter ego on may belong to a time long since passed, the issues and persona that drive the project couldn’t be more current.

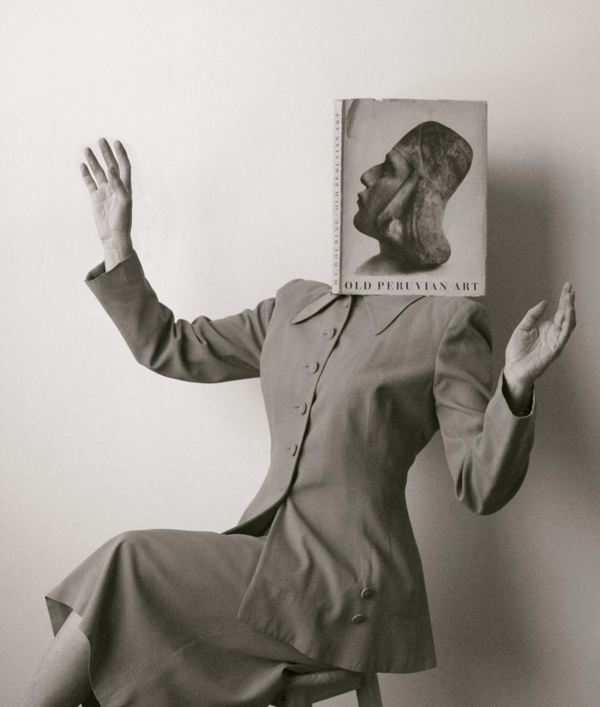

Natalie Brettschnedier performs “Moche Warrior,” 1949. Digital ink jet print on archival paper.

Natalie Brettschnedier performs “Moche Warrior,” 1949. Digital ink jet print on archival paper.

Rediscovering Dada’s Women

In the course of researching precedents for my own interdisciplinary art practice, which encompasses music, photography and performance, I have been frustrated by a shortage of information about women artists making interdisciplinary work in the early 20th century. Despite tantalizing mentions of singers and other performers involved in Dada and Surrealism, the narrative conventions of art history tend to emphasize key male “geniuses” and downplay or omit altogether the contributions of women. In general, painters and sculptors leave more tangible evidence of their practices than performance artists, and are therefore easier for art historians to talk about. Nonetheless, it seemed odd to me that pivotal figures like Emmy Hemmings, who co-founded the Cabaret Voltaire with Hugo Ball, were mentioned only in passing in the histories that I was able to access when I began this project in 1998. In the ensuing years, feminist art historians have worked to redress this imbalance. Publications such as Ruth Hemus’s book Dada’s Women explore the mechanisms by which women have been excluded from past histories, and work to correct the omissions, but there is still much left to discover.

The Natalie Brettschneider archive is constantly expanding and evolving as more of her activities come to light. The texts, photographs and objects contained in it provoke questions about the ways in which historical narratives are subjective portraits, shaped by the priorities and ideologies of individual authors. I am curious about the criteria scholars use for deciding what to leave out and what to preserve, what is the centre and what is the periphery, what is high art and what is low, and what is important and what is not. The following examples from the Brettschneider archive illuminate the work of less well-known women artists and musicians, who I encountered in the course of my research, whose groundbreaking interdisciplinary works deserve wider attention.

Nellie Duke’s house quake, Kelowna, 1939. Digital ink-jet print from original negative. 4.5 x 5 inches.

Nellie Duke’s house quake, Kelowna, 1939. Digital ink-jet print from original negative. 4.5 x 5 inches.

Shaking Off Status Quo Expectations

In 2008, Kelowna Art Gallery curator Liz Wylie invited me to research Brettschneider’s activities in the Okanagan region of British Columbia. I spoke with a number of longtime residents there about local women artists of Brettschneider’s generation, and several of my interview subjects mentioned Nellie Duke, a British expatriate opera singer, voice teacher and amateur painter. She had followed a Canadian soldier back from England after the First World War, only to discover that he was already married. She continued west, and used her dowry money to buy a piece of land near Kelowna. Over the course of many years she singlehandedly built a little house there—making up the design herself as she went, scrounging wood from nearby building sites and talking people into helping her transport materials or assist with the construction in some way.

Learning about Nellie Duke, I was reminded that many women of her and Brettschneider’s generation did not marry. Women outnumbered men in their age bracket, because so many of their male contemporaries had been killed in the First World War. They were forced to find their own ways and figure out how to support themselves, which constrained many financially, but also allowed them a certain amount of independence. The photograph of Duke’s house found in the Brettschneider archive, and the accompanying text, honour Ms. Duke’s resourcefulness and creativity in building her own house, an impressive durational, site-specific performance. It is exciting to imagine Brettschneider and Duke making the house shake with their powerful operatic voices.

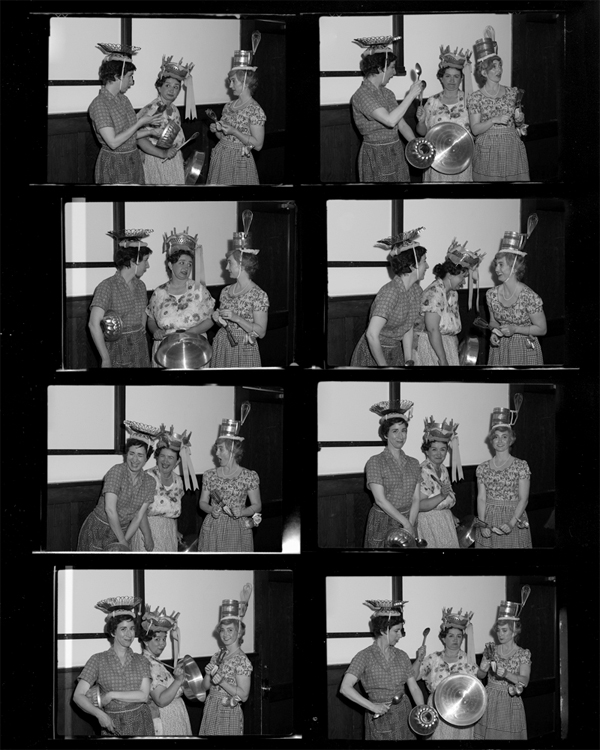

Natalie Brettschneider with friends Lori Weidenhammer and Soressa Gardner, 1951. Ink-jet print from original vintage contact sheet, 8 x 10 inches.

Natalie Brettschneider with friends Lori Weidenhammer and Soressa Gardner, 1951. Ink-jet print from original vintage contact sheet, 8 x 10 inches.

Ensemble Trois Femmes Mécaniques (ETFM), promotional photograph, ca. 1958. Digital ink-jet print from original vintage print, 12 x 14 inches.

Ensemble Trois Femmes Mécaniques (ETFM), promotional photograph, ca. 1958. Digital ink-jet print from original vintage print, 12 x 14 inches.

Striking Up the Avant-Garde Band

In 2012, I visited the Surrey, BC, archives to discover more about Brettschneider’s activities in that region, for the exhibition “Scenes of Selves, Occasions for Ruses,” curated by Jordan Strom at the Surrey Art Gallery. I found some interesting press photographs that documented activities of the Surrey Junior Chamber of Congress, including fancy-dress balls, parades and, in one sequence of images, an all-female pot-and-pan band. Brettschneider, recently returned to Canada from Paris, saw the potential this kind of vernacular performance held for avant-garde music making. The Surrey archives photograph led to a whole sequence of Brettschneider images documenting various noise-based musical ensembles employing household objects, including this trio that appears to be backstage at a concert, and the later promotional photograph of the Ensemble Trois Femmes Mécaniques (ETFM), both of which show Brettschneider with her frequent collaborators Lori Weidenhammer and Soressa Gardner. A recently discovered and restored photograph captures Brettschneider performing with a small ensemble at the Booth House in Ottawa who are playing, among other more conventional instruments, a large trophy bowl, a cardboard box and a pot lid.

Natalie Brettschneider and unknown ensemble, Booth House, ca. 1947 Digital ink-jet print from original negative, 16 x 20 inches.

Natalie Brettschneider and unknown ensemble, Booth House, ca. 1947 Digital ink-jet print from original negative, 16 x 20 inches.

Natalie Brettschneider performs Triangles, ca. 1933. Digital ink-jet print from original negative, 5 x 7 inches.

Natalie Brettschneider performs Triangles, ca. 1933. Digital ink-jet print from original negative, 5 x 7 inches.

Making Connections

Since 2014, I have been researching Canadian pianist and harpsichordist Frances Barwick, who, like Brettschneider, lived in Paris in the interwar years. Barwick’s substantial gift led to the founding of the Carleton University Art Gallery, where the Brettschneider archive is currently on exhibit. I spent a week in Ottawa at CUAG and the Library and Archives Canada, sifting through their Barwick archive, which includes correspondence, photographs and other documents. With the help of curator Heather Anderson and research assistant Leanne Gaudet, I was also able to study correspondence and photographs at the archives of the National Gallery of Canada from the fonds of Barwick and her brother Douglas Duncan, who ran Toronto’s Picture Loan Society gallery.

It is unclear whether Barwick and Brettschneider ever met, but some of the items in the Barwick papers nonetheless shed new light on Brettschneider’s activities. For instance, a small photograph in the Brettschneider archive with the cryptic notation on the reverse, “M. M-S. Triangles, 1934,” could be connected to material in the Barwick archive related to an exhibition at the prestigious MM. Bernheim-Jeune Galleries by the sculptress M. Molyneux-Seel. This file contains a press clipping, invitation card and list of works—including a sculpture titled Triangles. The photograph could be a study for the artwork, but it would be difficult to verify this. The accomplished Molyneux-Seel, whose subjects include many famous figures from Parisian artistic circles, including composer Virgil Thompson, photographer Ilse Bing and dancer Doryta Brown, seems to have nevertheless vanished from the annals of art history without leaving a trace. The gallery, although still in operation, only has the exhibition invitation on file, and was unable to supply us with any further information about the artist. An extensive Internet search yielded only one mention—the Molyneux-Seel portrait of Thompson resides with his papers at the Yale University Music Library.

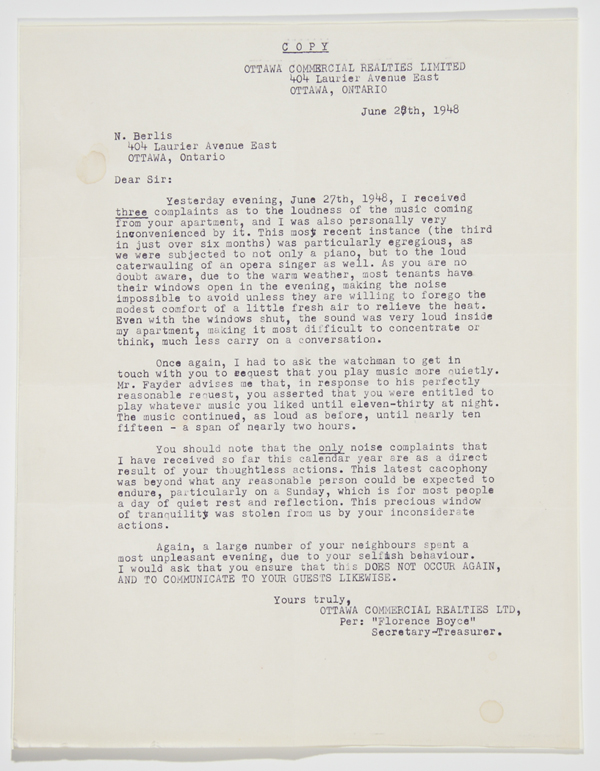

Berlis Noise complaint letter, June 28, 1948. Typewritten document on laid paper, 8.5 x 11 inches.

Berlis Noise complaint letter, June 28, 1948. Typewritten document on laid paper, 8.5 x 11 inches.

Erupting Radical Noises

Another serendipitous discovery in the Barwick archive sheds new light on another peculiar document in the Brettschneider archive—both collections contain very similar letters addressed to a Mr. Norman Berlis at 404 Laurier Avenue in Ottawa (the still-standing Stratchona Apartments). Each of the letters complains of unreasonable noise coming from Berlis’s apartment. The Barwick archive document is written in response to some loud piano playing, noted in Francis Barwick’s handwriting as “F.B. playing a Bach partita about 9:30 pm!” The Brettschneider archive letter, dated a few months later, complains of a pianist and loud singer. Although it is likely that the loud singer in question was Brettschneider, and tempting to think that the pianist accompanying her was Barwick, the exact details are not known. At the CUAG vernissage, some musical collaborators and I will perform some of Brettschneider’s repertoire, accompanied by one of the harpsichords that she donated to Carleton’s Music Department.

Researching the activities of Brettschneider has provided me with a fascinating window into the nature of archives and the pleasures of researching within them. It can seem quite random what kinds of documents get preserved—often, they contain a jumble of fragments and ephemera that remain enigmatic and opaque until a researcher is able to piece them together to form a coherent whole. I hope that by bringing the activities of Brettschneider and her contemporaries to the public, I will inspire the viewer’s curiosity and interest in the work of women artists, and encourage them to contemplate the ways in which history is a kind of construction that reflects the narrative conventions, critical framework and assumptions of the cultural context in which it is written.

“Carol Sawyer: The Natalie Brettschneider Archive” runs from January 18 to April 19 at the Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa.

Natalie Brettschneider, Rapunzel and Medusa sit down to chat about war, c. 1947, digital ink jet print on archival paper'

Natalie Brettschneider, Rapunzel and Medusa sit down to chat about war, c. 1947, digital ink jet print on archival paper'