Walking into the photographic storage facility at the Ryerson Image Centre, the $71 million, Diamond Schmitt Architects–designed expansion of Ryerson University’s School of Image Arts in the heart of downtown Toronto, is a little like entering a top-secret vault: key cards are involved, and heavy air-locked steel doors, and inside everyone is wearing nitrite gloves and speaking in hushed tones, barely audible over the hum of the climate-control system that keeps the air cool and dry. Stored in archival boxes filed in tall, moveable metal shelves are the 292,000 black-and-white images that compose the Black Star Collection, an archive of prints from the legendary Black Star Agency in New York donated to Ryerson in 2005 along with an additional $7 million to house and maintain the collection.

In an era in which most photographs are viewed on the screens of laptops and smartphones, it cannot be emphasized enough that the Black Star Collection is an assemblage of physical objects (only about 30,000 of the images have been scanned thus far), most of them prints of images taken by photojournalists out on assignment. The prints are stored in Black Star’s subject order, and since the collection has yet to be properly archived (at the current pace, it won’t be fully digitized for another eight years), no one has full knowledge of what is in it. Which means that sifting through the prints in any given box pulled off the shelves is a lot of fun. One could encounter a photograph of Chairman Mao consulting with his general during the Long March, or a portrait of the Duke and Duchess of York, or an image of Hasidic Jews kibitzing on the streets of Brooklyn. There are familiar, iconic photographs as well: a grizzled GI swigging from a canteen on Saipan during the Second World War; Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller sauntering across an airport tarmac; John. F. Kennedy, his children and his dog walking along the beach in Martha’s Vineyard. The attributions and context for the photographs, when there are any, are scribbled on the back of the prints.

In 1935, Ernest Mayer, the owner of the Mauritius picture agency in Berlin, fled the Nazis for New York, bringing with him some 5,000 prints, many of them dating back to the First World War. Once settled, Mayer connected with two other German Jewish refugees from Hitler’s rise to power, Kurt Kornfeld and Kurt Safranski, and together they founded the Black Star Agency. The mid-1930s was a prescient time to start a photojournalism agency—Newsweek was founded in 1933, Life in 1936, and both were major clients of Black Star early on—and Mayer, Kornfeld and Safranski were able to bring sophisticated European visual sensibilities to the nascent North American magazine industry, with revolutionary results. The 6,000 photographers who worked with Black Star over the more than half a century during which the agency focused on black-and-white photography, some of whom, like Bill Brandt, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andreas Feininger, W. Eugene Smith and Roman Vishniac, are now regarded as important artists in their own right, effectively invented the magazine photo essay and created an unparalleled visual history of the 20th century.

At the dawn of the 21st century, however, Black Star’s archive was taking up valuable real estate in the agency’s Manhattan offices; the prints were of diminishing commercial value for the agency, which had moved on from both black-and-white photography and photojournalism. In the meantime, art and cultural historians, and the universities and museums that support them, had become increasingly interested in the history of photojournalism: not only do collections like Black Star’s provide a window into the way history is represented, but even the humblest Black Star hacks were on an aesthetic continuum with great street photographers like Weegee, Harry Callahan and Robert Frank. In 2003, an anonymous donor went looking for a Canadian institution capable of housing and managing the collection. Ryerson University was on the list.

That Ryerson should have been the principal candidate for what turned out to be the largest donation of cultural property made to a Canadian university should come as no surprise. Not only does Ryerson have one of the most respected photography programs in North America, it also already had a substantial collection of fine-art photography, and had recently launched, in conjunction with the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York, an MA program in photographic preservation and collections management. And the university had been planning a major expansion of its School of Image Arts for 18 years, held back only by its inability to raise the necessary funds. The Black Star Collection was offered to Ryerson in 2004, made public in 2005, and by 2006 the university was looking for an architect to design the Ryerson Image Centre. The result is a world-class facility that includes the Ryerson Gallery, whose inaugural exhibition, “Archival Dialogues: Reading the Black Star Collection,” curated by Ryerson Image Centre director Doina Popescu and writer and curator Peggy Gale, opened at the end of September.

Set on the western side of the Ryerson Image Centre and surrounded by a rambling student lounge, the Ryerson Gallery is itself an impressive addition to Toronto’s cultural landscape: with high ceilings and white-oak floors, the gallery is equipped with museum-quality climate control and lighting, which means it will be able to exhibit both contemporary art and sensitive historical works. “Our logo says, ‘Gallery, Research, Collections,’” Popescu tells me. “The gallery has a triple mandate: to interact in a multidisciplinary way across the campus, to engage students and also to be a public gallery that offers a new voice and one that reaches out internationally.” The gallery’s exhibitions curator, the photographic historian Gaëlle Morel, adds, “we’re going to try to juxtapose different perspectives and try to show how the art field and the media field are closely interconnected, and how the boundaries are not all that clear.” “Archival Dialogues,” which included a roster of eight well-known Canadian artists (Stephen Andrews, Christina Battle, Marie-Hèlène Cousineau, Stan Douglas, Vera Frenkel, Vid Ingelevics, David Rokeby and Michael Snow), was an initial foray into exploring the centre’s multifaceted mandate.

One of the innovative features of the Ryerson Image Centre is the Salah J. Bachir New Media Wall, located in the glassed-in colonnade at the entrance to the gallery, which, not surprisingly, was commandeered by new-media artist Rokeby for his contribution to “Archival Dialogues.” “I went to the Black Star Collection and found myself in a strange state,” Rokeby says. “I found myself picking through random photographs, and I was interested in the way my eye handled detail—a lot of my work since the 1990s has been about how the eye digests detail. I decided to do a piece about how the eye digests detail in famous images, and there are many in Black Star. I’m blurring the detail that makes the image famous, then creating a scripted revelation.”

Rokeby’s work concerns the way we process visual information; Douglas’s Midcentury Studio (2010–11), by contrast, explores the history of photography and photojournalism. “As research for Midcentury Studio, I looked at thousands of photographs in the Black Star Collection,” Douglas tells me. “I was seeking out ‘incompetent’ images—in the 1940s and 1950s, a lot of photojournalists were learning their craft on the job. So, for my piece, I adopted the persona of a person who is learning his craft as he plies his trade—I’m fascinated by the information that comes through as a result of the fact that the apparatus essentially took over for them and did things they would not know how to do. I think that accounts for a lot of the surrealism of these images.” Ingelevics’s Conditional Report (2012), on the other hand, examines the physical reality of the archive—he even built a simulation of the vault in which the Black Star Collection was housed at an off-site storage facility before it was moved early last summer to its permanent home in the Ryerson Image Centre and set just outside the entrance to the gallery. On either side of the structure are rear-projection videos: in one, a lone woman is plodding away at the staggering task of scanning the collection, one photograph at a time; in another, huge printouts of iconic images from the collection are being shredded after an exhibition; and in still another, workers are wheeling the collection into the not-quite-finished building.

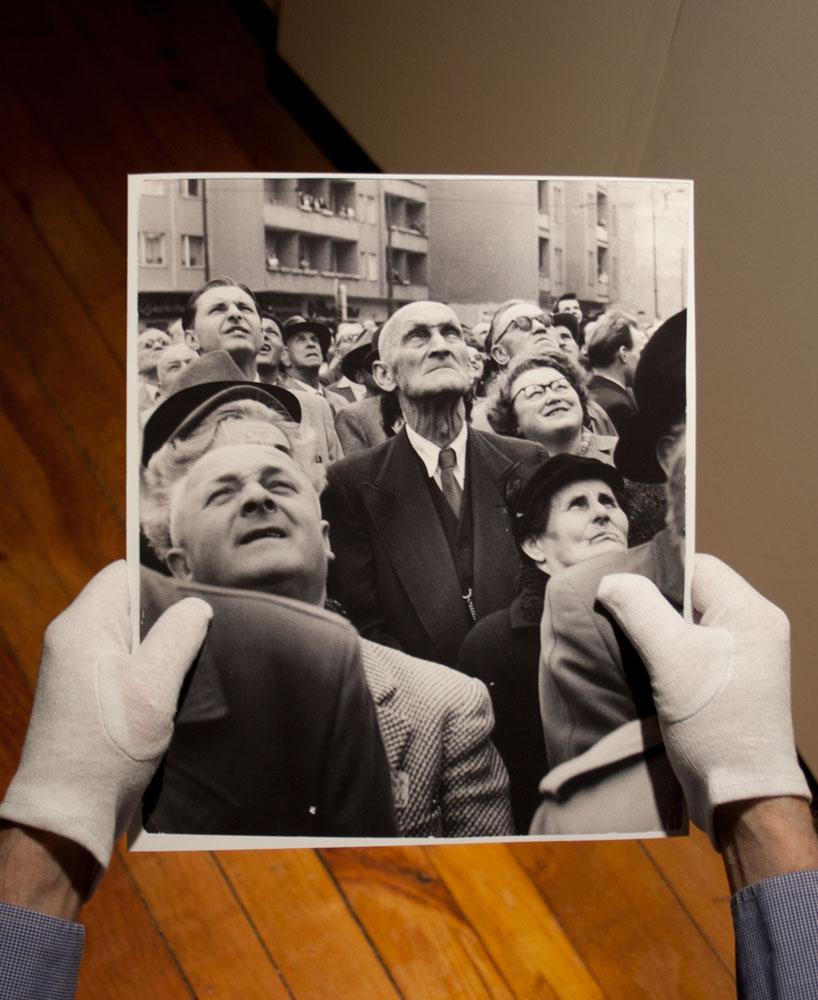

The Black Star Collection provided rich material for the artists in “Archival Dialogues,” and one can almost feel how much fun they had riffling through the endless prints: Battle looks at images of disaster; Cousineau investigates the depiction of the North and the Inuit; Frenkel ruminates on images of exile and migration; Snow finds photographs of crowds; and Stephens gathers Lee Harvey Oswald images. The problem is that while the Black Star Collection is a fascinating random sampling of 70 or so years of looking at the world through the lens of a camera (and what isn’t in it is almost as interesting as what is), the photographs themselves are of mostly historical interest—the cutting edge of “lens-based” art has long since left discussion of the indeterminate boundaries between art and media that Morel sees as part of the Ryerson Gallery’s core mission far behind. Indeed, it’s not obvious that the supposed boundaries between art and media were ever all that determinate: when Peter Higdon, Ryerson’s collections curator, shows me a print that W. Eugene Smith had made of his staggering Minamata pietà, Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath, Minamata, 1972 (1972), a version of which originally appeared in Life and which has been in Ryerson’s collection for years, the issue seems about as relevant as whether Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War prints (1810–20) are art or documentation.

The gallery’s programming over the next year is worthy: “Human Rights, Human Wrongs,” which will feature some of Black Star’s images of the civil rights movement; “Alfredo Jaar: We Wish to Inform You That We Didn’t Know”; “Clive Holden, Un-American (Un-famous),” a work for the New Media Wall that draws on the Black Star Collection; and “Gabor Szilasi: The Eloquence of the Everyday.” But is it visionary? If the Ryerson Gallery is going to be something more than an academic institution with spectacular facilities, if it going to be a “new voice,” as Popescu insists, it will have to do more than revisit issues about the relationship between art and documentation and the veracity of photographic representation. It will have to widen its mandate and explore the expanding reality of images beyond conventional photography and media.

Fortunately, there is plenty of time.

This is a feature from the Winter 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Michael Snow TAUT 2012 Production still Courtesy the artist

Michael Snow TAUT 2012 Production still Courtesy the artist