1. Richard Mosse’s The Enclave at the DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art

How does one make the invisible visible? That question preoccupies the documentary work of Irish artist Richard Mosse. Early this year I saw his most recent series, The Enclave, in its Canadian debut at DHC/ART and it was everything I had expected it to be: beautiful, troubling and powerful. The Enclave is a multi-channel film installation shot in the Democratic Republic of the Congo that has stirred controversy since its Venice debut in 2013 for its deeply aesthetic representation of an ongoing humanitarian disaster, which has left 5.4 million people dead from war-related causes since 1998. In reaction to a news media that have long since lost interest, Mosse’s work looks to bring attention in a radically different way.

Aside from this disenchantment with traditional photojournalism, The Enclave operates as a window through which to view the difficult and the ugly. Yet the aestheticization of human suffering in photography is an ethically problematic area that critical thinkers have repeatedly attempted to reconcile. And The Enclave’s beauty is undeniable. It fuses documentary and cinema—sweeping vistas, slow pans through villages, shots of jungle warfare, houses moved by hand and gory caesarian birth—and has a haunting electronic soundscape by Ben Frost.

“You know. It’s Africa—but pink!” I find myself saying when trying to see if others are familiar with the work. But instead of playing into the stereotype of a bright and colourful Africa, the pink of the Kodak Aerochrome film stock that Mosse uses suggests a sickly, psychedelic, alien world of poverty and cyclical violence. Granted, Africa is exoticized by such a depiction, which confirms the Western conception of the continent as always dying, always poor and always violent. Having visited Kivu while I was living in East Africa, I have the DRC’s narrative of war firmly implanted in my mind. Perhaps I am so drawn to The Enclave because it is exactly the opposite of what the reality looks and feels like, such a clear exaggeration and disconcertion. Part of the power of Mosse’s work is now the debate that now surrounds it. Whatever else it is, it is an incredibly visceral and memorable experience.

2. Doris Salcedo at the Guggenheim

Cement-filled wardrobes, clothes made from burnt needles, hair sewn into furniture, grass sprouting from tables: the domestic, and all its comforts, goes awry in the deeply poetic work of Colombian artist Doris Salcedo, on view in her retrospective at the Guggenheim this past summer. Her work focuses on the everyday death that has become Colombia’s reality and the disappeared that are markedly a part of South America’s story.

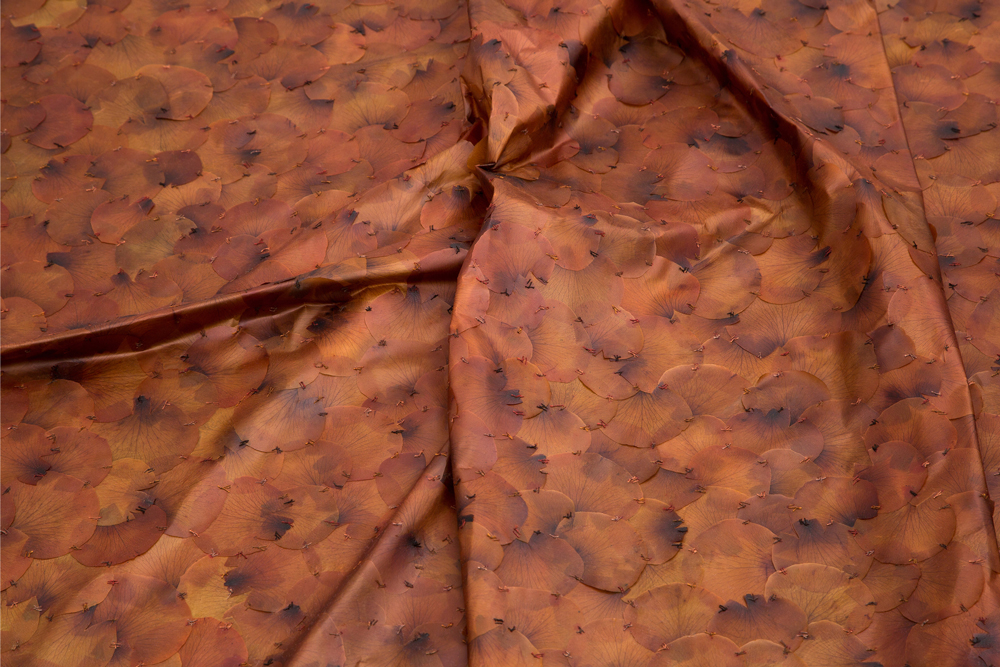

Each floor of the Guggenheim gave way to large white rooms filled with Salcedo’s work in a show that resonated with sadness. Among the many floors I was drawn to the maze of upended tables in Plegaria Muda that reminded me of coffins protruding from the earth. In Untitled, stacks of crisply laundered white shirts are each impaled by a single metal rod. A Flor de Piel features a huge wrinkled quilt made from preserved rose petals sewn together with thread, which is ominously reminiscent of a vast sheet of human skin. The piece was clearly labour-intensive, made in memory of the torture and death of a nurse, though it spoke about the wider impact one life can have, covering the floor of an entire room, unfurling and folding into its corners.

Salcedo’s work is both elegiac and active, letting singular stories represent broader issues of violence in an attempt to visualize the enormity of the issue and protest its political origins. I thought about other Latin America artists who have made work that is both political and mournful: Mexican artist Teresa Margolles using water she reconstituted from morgues, or Alfredo Jaar remembering the genocide in Rwanda through the eyes of Gutete Emerita.

Poetics and death appear appropriate to public art in Colombia, as a short film at the Guggenheim about Salcedo’s site-specific installations made apparent. I couldn’t help but compare the work she made in Istanbul—1,550 chairs stacked into the void between two homes—to the mass ritualization in Europe and North America of the “Great War,” with wreaths and marching bands and minutes of silence that speak to the huge difficulty a public has with processing great loss. Salcedo reflects a similar sentiment, while treating much more recent violent occurrences with a delicacy and care that those being remembered did not receive in life. But memorials assist the living, carrying forward the spirit of the individual and, perhaps, creating enough impact to enact change.

3. “The pen moves across the earth: it no longer knows what will happen, and the hand that holds it has disappeared” at the Blackwood Gallery

In 2015, public consciousness on climate change and environmental degradation took full form. What was the hottest year on record also saw California’s worst drought in a millennium, heat waves in the Indian subcontinent that killed thousands and man-made, self-sustaining forest fires in Indonesia described by the Guardian as the “greatest environmental disaster of the 21st century.” As world leaders met in Paris last week to decide whether this might get in the way of making money, artists in Mississauga showed work for a group exhibition curated by Christine Shaw depicting an earth that has already reached the point of no return.

“The pen moves across the earth” visualised the characteristics of the Anthropocene, the current geological epoch in which the human being has become the most important and effective actor on the earth’s geological processes. The pain the earth feels is apparent in Pascal Grandmaison’s Nostalgie #1 in which a large boulder grates and clanks along the ground in an ode to the Grecian myth of Sisyphus. Kara Uzelman’s Magnetic Stalactitewobbles and hangs ominously from the gallery ceiling. Made entirely from scrap metal found near the gallery and held together only by magnets, it is a pleasing interpretation of the trepidatious state of play as well as the socioeconomics of its construction from ores to metal to junk. In the centre of the space is Robert Wysocki’s Post Metal, the attention-grabbing 30,000-pound sand dune being slowly sculpted by a wall of fans. The nest of wires visible behind the fans acts as an accidental reminder of the technological apparatuses now centre stage in our lives.

Just below the surface of the exhibition’s environmentalism is the ideology of deep ecology that posits the earth as a singular organism, a Mother Earth if you will, whose own aesthetics may be an aid in the fight to save it. I left Shaw’s exhibition feeling uplifted and more aware of the simple gestures that have become so part of daily life they appear mundane. Rather than the violence of resource-extraction, we need to reposition our thinking away from the anthropocentric and towards ecocentrism. “The Pen moves across the earth” carefully anticipates this hopeful return.

Doris Salcedo, A Flor de Piel (detail), 2014. Installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Photo: Patrizia Tocci.

Doris Salcedo, A Flor de Piel (detail), 2014. Installation view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Photo: Patrizia Tocci.