“I like stuff,” Barbara Astman said recently, remembering her early days in Toronto. She had moved from her hometown of Rochester, New York, in 1970 to attend the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University), where she still teaches today. Wanting to get to know her new city, she spent a lot of time wandering through the “jobbers” of Kensington Market, Spadina Avenue and Queen Street West. She found inspiration in the colours, patterns and textures, as well as the self-referential order and colour coordination of the fabric and hardware stores, scrap bins and the Goodwill on Richmond Street.

“I would stand in the middle of the store,” she recalled, “and be flooded. I knew it was informing me, but didn’t know how until I was making something.”

Through advances in digital imaging, Astman eventually created her own store, stocked with black-and-white souvenir merchandise, in Dancing with Che: Enter Through the Gift Shop (2011–13). It travelled to several art museums across Canada, most recently to the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in the summer of 2013. A blurry image of Che Guevara, animated through Astman’s dancing body, appears on mugs, T-shirts, tote bags, plates and more. Painfully, none of the stuff is for sale.

In the fall of 2013, Astman worked on a project facilitated by Canadian designer Jeremy Laing to produce a line of limited-edition silk scarves for Toronto fashion boutique Jonathan and Olivia that are based on her Newspaper Series (2006–08).

Astman’s play with fabrics and props harks back to the room she was renting in the early 1970s in a house at 56 Beverley Street, which was also her studio. Her small space resembled one of those “jobbers,” as it was filled with fabrics, masks, beads and other stuff she picked up because she was intuitively attracted to it. It was also in this room that Astman discovered, quite by accident, the camera. She had borrowed one to document the large aluminum sculptures she was making at the time, and there was some film left. She brought it home, pinned up fabric on the wall and began acting out private performances with her masks and veils. When she developed the contact sheet she realized that she had found her tool. “There was something happening in these self-portraits that spoke about things I was really interested in, in a much more direct way,” she said. Astman was 22.

It is a common story among artists of her generation, often women artists, who stumble upon photography while enrolled in traditional painting or sculpture courses and realize that the camera is their “weapon of choice,” as it’s called by US artist Laurie Simmons, known for her photographs of dolls in miniature domestic vignettes. “I was not getting there with the drawings or ceramics,” Astman acknowledges. “The ideas were not gelling with the medium, until [I used] the camera.”

Acting out in private in front of the camera is the germinal process at the core of Astman’s most iconic and celebrated large-format photo-based series: Untitled, i was thinking about you…Series (1979–80), Red Series (1980–81), Scenes from a movie for one (1997) and dancing with che (2002). She uses her image to evoke an emotive narrative—rooted within her psyche and based on her own lived experience, completed in the viewer’s imagination—through carefully orchestrated compositions of poses, gestures, colour, textures and a full range of everyday-life objects. Typically, her solitary figure is framed in a square, cropped from just below the eyes to her knees, yet the effect is quite the opposite of the classical nude torso. Even in Scenes from a movie for one, where serial images of her distorted face and naked upper body are individually ghostly yet cumulatively assertive, Astman’s figure is self-determined and self-aware.

How do we make sense of these images, which feature the artist’s image at the core of the production of meaning, as revolutionary in our current age of “selfies,” Instagram, Tumblr and Snapchat?

Instant photography has been Astman’s full partner in art and imagemaking since the mid-1970s. She was born in 1950 and raised in Rochester—then the world’s headquarters of image- and lens-technology heavyweights Eastman Kodak, Xerox and Bausch and Lomb. The bigger world flowed into her consciousness, expanding it beyond her family and middle-class suburb through images in the newspapers, on television and in travelogue movie nights organized by Eastman Kodak. As a child, Astman remembers watching her father George take apart their brand-new television, lay out all the parts on the living room floor and then put it back together to figure out how it worked. He had a compulsion and a curiosity that Astman recognizes in her own practice. “I was always aware that technology can change your life. I was curious about how it worked,” Astman said. She sought a technology that could respond as quickly as her thoughts formed and one that she could handle “to get the image the way I want it.”

Her indispensable tool has been the Polaroid camera, which she purchased as soon as it became available and affordable. “I bought a Polaroid SX-70 camera in January and it changed my life,” Astman said in a Saturday Night interview in 1978. “I like modern technology. I like to get my ideas across fast,” she continued.

Technology allowed Astman to mine and access her inner world, from which she imagines and creates. She explored the notion of travel, both real and imagined, in several series over the years, most resourcefully in the Color Xerox Murals (1976)—early collaged xerographs of herself or her friends in exotic locales—and in her recent digitally stitched murals of postcards, Wonderland (2008), based on a shoebox filled with post–Second World War postcards of US cities she bought at a Rochester garage sale in the 1980s.

She is surprisingly and deliberately low-tech, despite both her technical proficiency and her reputation as an important innovator in the use of photography as art. “I’m interested in process and in materials,” she declares.

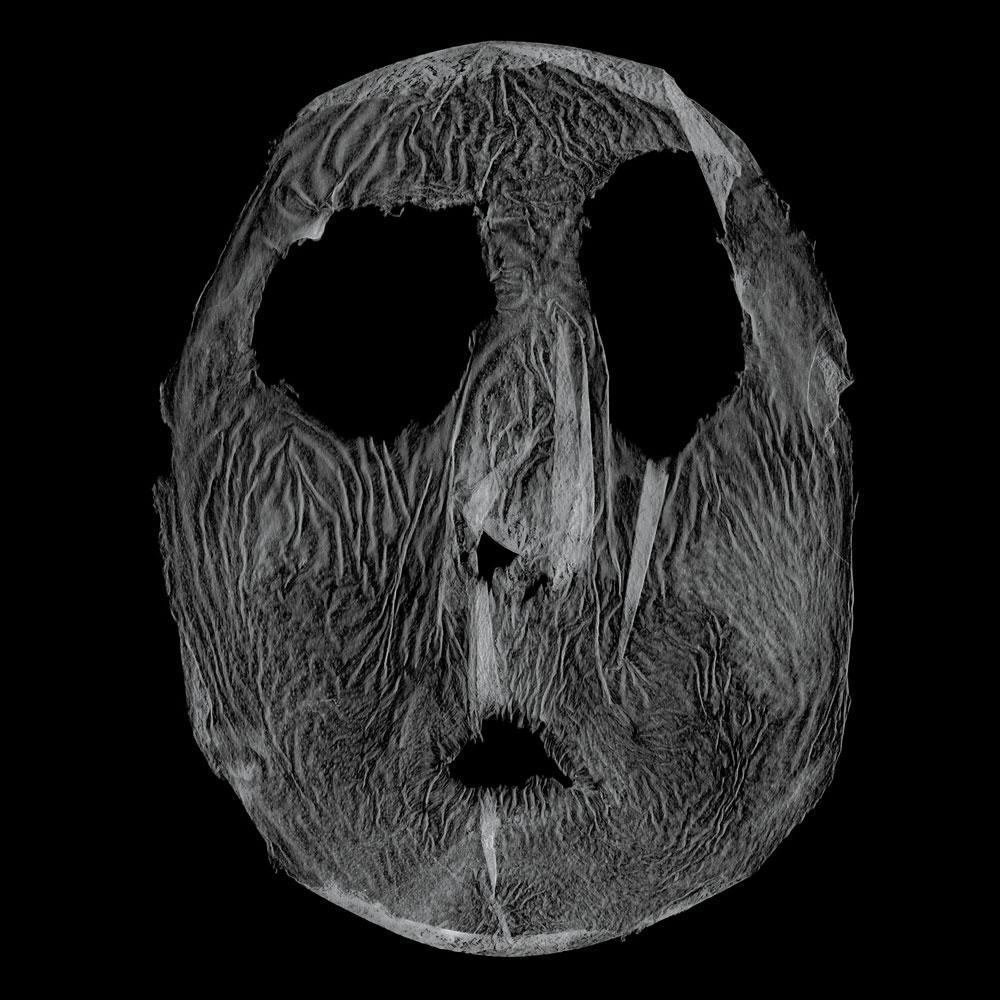

The shift to digital technology has been a process of exploring how to interact physically and intuitively with the immaterial image on the screen. She began to print digitally in 1994, in Untitled (Seeing and Being Seen), but it took her over a decade to fully embrace digital photography. “All my digital stuff starts with something handmade…and the printing is very important to me.” She has flipped through and photographed stacks of her daily newspapers in the Newspaper Series, made Daily Collages (2009–11) and scanned her peel-off masks in I as artifact (2013).

Early on, Astman experimented with photo-booth strips and appliqués, heat-transfers and photo-linens combined with fabrics, quilting, handwritten texts and painting, creating full sensory pieces such as Carol performing lilac tricks (1975). (Perhaps not unrelated, Astman emotionally recalled how her mother Bert, a homemaker, added love notes made from saved bits of paper and other such things, repurposed and collaged, in their lunch boxes every day.) The work, purchased the year it was made for the AGO collection by curator Alvin Balkind, is a black-and-white image of her ebullient younger sister Carol with a mouthful of lilacs in her parents’ backyard. Hand-tinted, the image is framed by purple satin, black lace and a fabric garland of lilac blossoms. At once mournful and exuberant, Carol is performing lilac tricks of both innocence and decadence.

As the easy-to-use, do-it-yourself technology developed and proliferated, Astman found new ways to co-opt it into her working practice. Initially, she had access to a colour photocopier when commuting home, as her older sister Judy worked for the vice-president of Xerox. A machine was then made available to local artists in Toronto—in Michael Hayden’s studio building on Shuter Street.

Drawing affinities with Robert Rauschenberg and Richard Hamilton, Astman embraced this new technology to transport herself or friends into imaginary worlds: her friend Myra Craven on the Grand Tour of Europe, herself to Florida, or painter David Craven through the history of Western and Canadian art. She has employed a related strategy in her most recent work, The Fossil Book (2013), commissioned for the Koffler Gallery’s inaugural show in their new space. Pages from an old text on fossils hang in a grid; its own diagrams of prehistoric creatures, enlarged and vibrantly coloured, journey across them, visiting each other’s textual habitats.

Astman’s early strategies of combining the latest image technology with a lovingly handmade look can be viewed in the current context of young females “still figuring it out,” as Tavi Gevinson, teen blogger and founder of the online publication Rookie, puts it. Gevinson plays with the digital cosmos like Astman played with the Xerox colour photocopier. They share an ability to usurp and repurpose the tools of new technologies into handmaidens for a homemade vision of the world and our individual selves in it. It is even more remarkable that Gevinson’s press portrait, by OCAD University student Petra Collins, is an unconscious homage to Astman’s xerographic collage Patriotic Portrait (1975), employing the US flag as a serial backdrop to frame a young woman’s three-quarter portrait: staring solidly into the camera, head slightly turned, long hair comfortably worn.

Astman’s work in Karyn Allen’s groundbreaking “Colour Xerography” exhibition in 1976 at the AGO attracted the attention of her first dealer, Jared Sable. For the next 14 years, she was able to develop and mature through a series of key exhibitions at the Sable-Castelli Gallery, one of Toronto’s premier commercial galleries. She was one of only three women artists represented, along with Mia Westerlund Roosen and Suzy Lake.

It was the Polaroid, above all other technologies at hand, that presented Astman with everything she was looking for in a collaborator. Like her contemporaries Lake and Joan Lyons, she was interested in both the material and conceptual properties of photography, not in its documentary or snapshot usage. The Polaroid offered an immediate, unique image, no grain, saturated colour and two-and-a-half minutes of malleable emulsion.

“Everything made sense through that camera,” she said. “If I didn’t have the Polaroid camera in my hands I would not have thought of how to do the typed Untitled, I was thinking about you…Series. It was the directness of doing it on the Polaroid: first thought, best thought. I would take a picture of myself, attach it on the graph paper already prepared with pencil marks, roll it through the typewriter and start typing stream of consciousness. There was no editing, no corrections.” Each typebar letter carved its own shape in the drying emulsion as it struck. The force of her thoughts became permanently incised into her own image. It was Astman’s own version of the Rosetta Stone, in her case carrying a tender and raw message of how memory becomes truth.

Astman also knew that these new single images, unlike the preceding Untitled (Visual Narrative Series) (1978–79), which is comprised of six enlarged, serialized Polaroid images and caption texts, had to be big; they had to be her size. It was a bold assertion. She worked with the technician who enlarged and printed her Ektacolor murals using the size of her wrist as the measuring device. The letters as well as her image became blurred through this process, further distorting the real from the remembered.

Making this work, she has remarked, was her membership card into the feminist art movement. What followed are Astman’s signature works, large black-and-red murals in which she demonstrates the use and function of common objects she has spray-painted red.

With the Red Series, Astman rejected the rules and made her own. The series had an immediate and resounding impact, marking a watershed moment in the history of visual production, along with that of Lisa Steele’s Birthday Suit with scars and defects (1974), Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1977–80), Suzy Lake’s Are You Talking to Me? (1979) and Barbara Kruger’s ongoing Untitled series of red-framed text-and-image billboards.

How can we understand how radical and audacious these images are, decades later, in the deluge of apparently daring self-expression? This acting out seems so familiar and common today that we might miss the original revolutionary gesture. There is an argument to be made, as Alicia Eler does in her ongoing “Theory of the Selfie” series on the art blog Hyperallergic, that “selfies shape our social networked identities.” This act is indeed one of courageous freedom of expression rather than mere Internet narcissism. When we sign in, sign up, join in, post and share, we are constructing for distribution our digital versions of ourselves—our avatars. Selfies would not be possible without the effrontery of Astman and her generation’s innate disregard of received values and perceived knowledge.

Yet there is a difference. Through selfies, we are acting out in public. Astman’s work is private alchemy.

Astman acts out alone in her psychic and physical space so that she can present to the rest of the world a growing, deeply personal understanding, rather than a daily report. She conjures up experiences from a depth within herself that is embedded in her own unknowable selfhood. Astman engages in a sharing to psychically connect; to become aware of the distance between and within us. Yet she makes us aware of the impossibility of truly knowing and sharing as the unsettling condition at the core of human existence.

This is an article from the Spring 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, visit its table of contents. To read the entire issue, pick up a copy on newsstands or the App Store until June 14.