James Nizam is a photographer who makes sculptures and a sculptor who takes photographs.

This reflexive descriptor can be ascribed to a particular modus operandi developed by the Vancouver-based artist over the past decade and, while hardly encompassing the entirety of his practice, it can be said to bind its central queries together.

The process goes something like this: Nizam first gains access to abandoned domestic structures, which, emptied of their former inhabitants, quietly await demolition. Within these bare, cloistered spaces, he stages a variety of both “soft” and “hard” interventions.

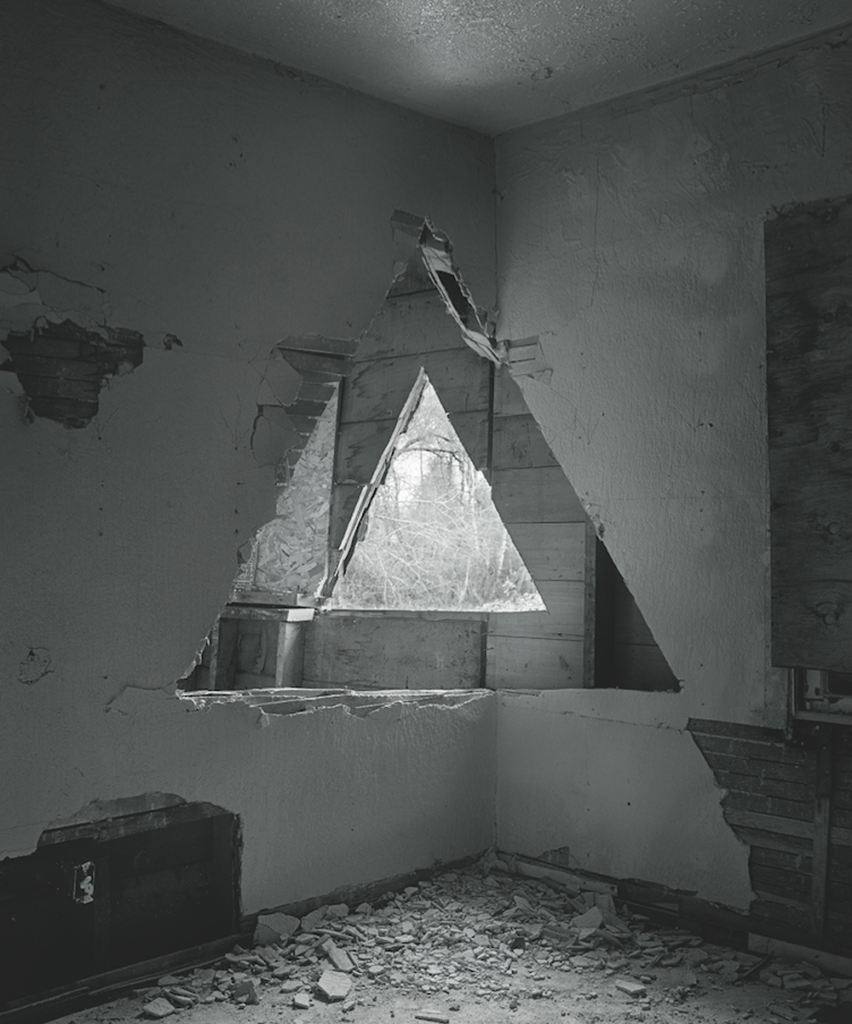

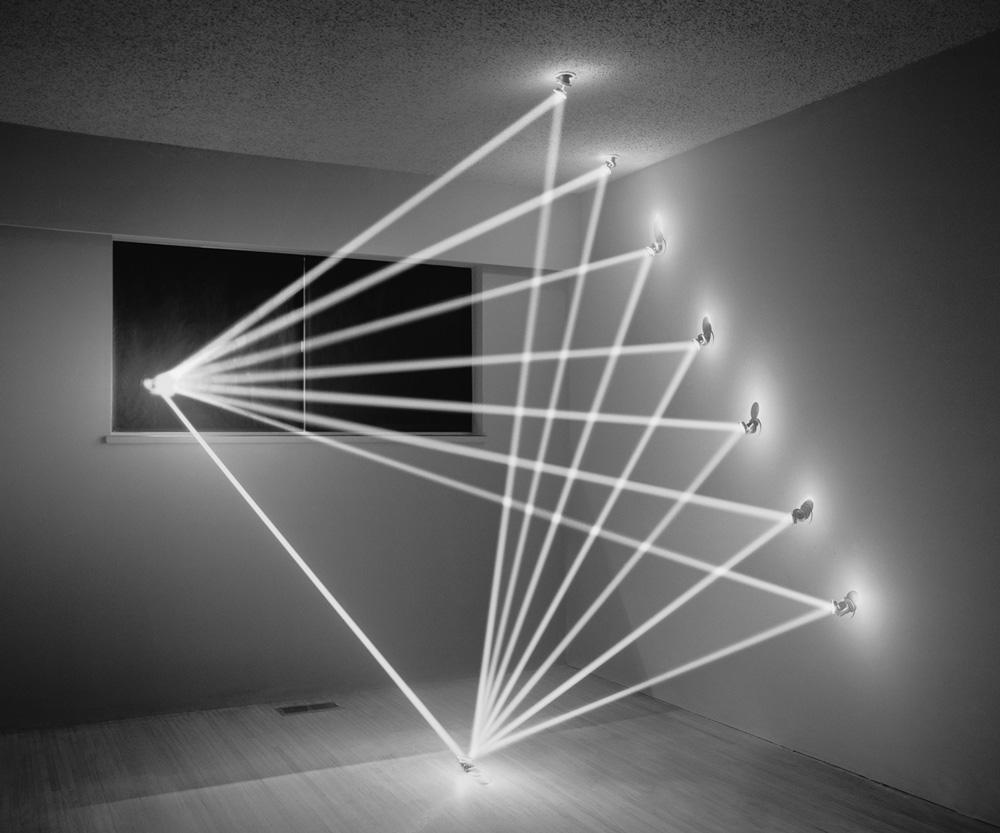

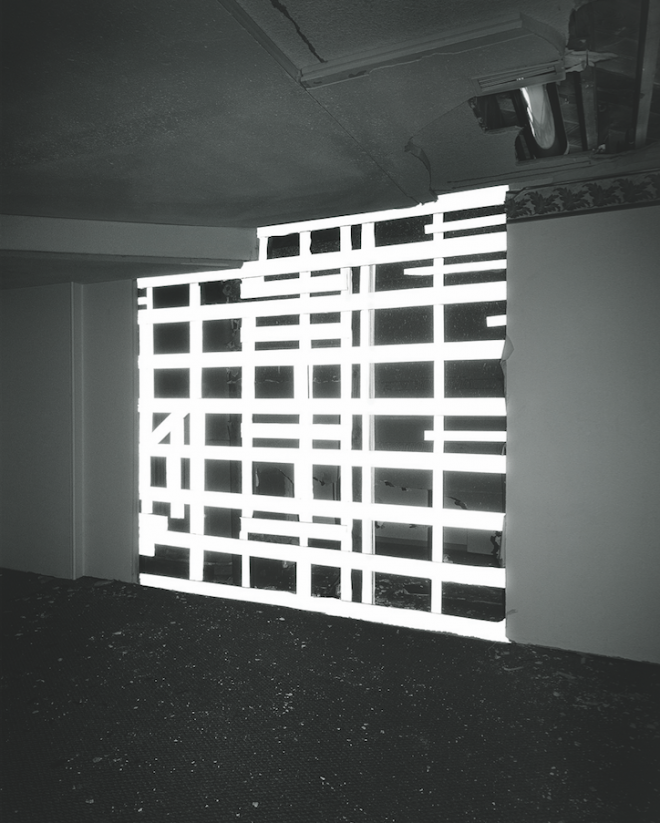

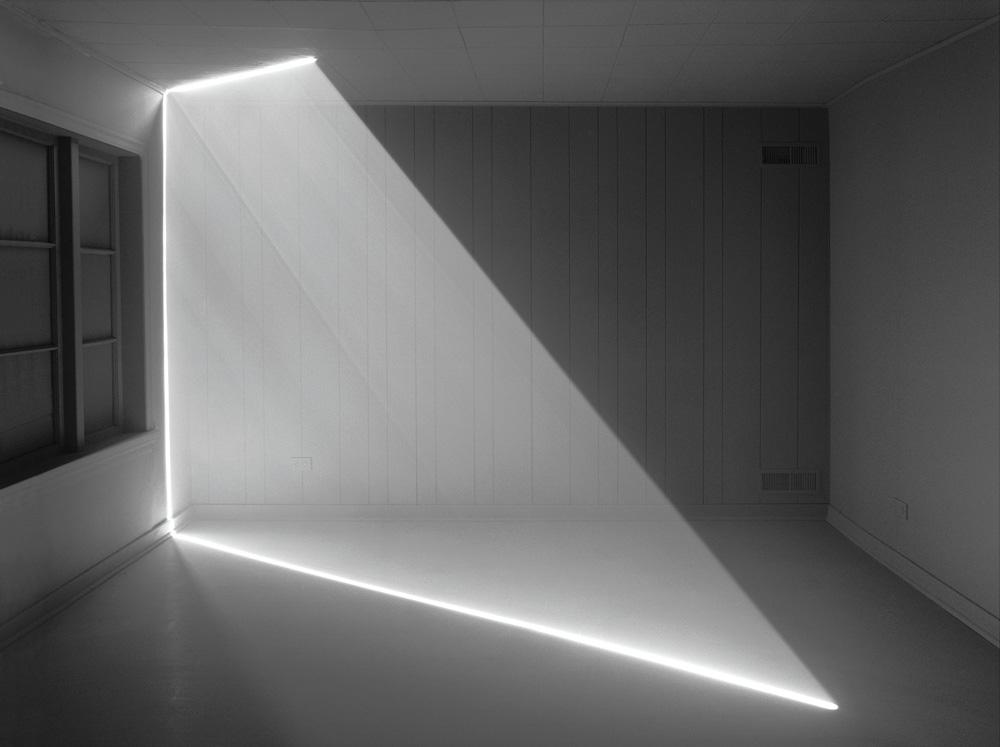

His Thought Form series (2011), for example, saw him limit the daylight entering a room to a tiny aperture, which he then directed, through a number of strategically positioned mirrors, into complex and ethereal geometric forms. In Shard of Light (2011), he made long, narrow incisions through walls and ceiling so that the sunlight cut a brilliant and curtain-like swath through the space. With Two Triangles (2013), the cuts—more muscular this time, and tunnelled through the walls of consecutive rooms to the outside world—took on a geometry through anamorphosis.

Nizam then photographs the results of these activities, sometimes using multiple exposures taken over the course of many hours. He works alone, making deliberate, calculated actions in the space, most of which are not available to viewers. Save for the odd exception, there is only the exquisite luminosity of the final, large-scale photographs.

Nizam’s most recent work, Illuminations Series (2015), was exhibited this past summer in Vancouver and Leipzig. It saw him once again visit empty domestic properties slated for redevelopment. As in his past work, Nizam’s choice of structure is recognizable as a particular type: modest, middle-class bungalows, built around midcentury. They are houses that in Vancouver’s current real-estate climate are rapidly disappearing from the landscape (and with little audible opposition).

In most works in the series, Nizam’s actions crossed the threshold from inside to outside. Working at night, the artist trained his focus on the exterior, non-structural details of the houses—their iron banisters and railings, awning frames, ornamental cinder block garden walls and screen doors. He wound these elements with reflective tape or covered them with reflective paint, then photographed.

Illuminated by flash, the isolated fixtures stand out in stark relief as dramatic and abstracted forms of light set apart from the shadowy contours of the houses. In the finished photographic prints, they seem to hover—like afterimages—on another spatial plane altogether, as though the forms are lifted from the realm of the mundane to now linger (beatified?) in some transcendental space.

Transcendental or otherwise, space is significant for Nizam. It is fundamental to the way he understands the possibilities of the camera: not as an image-taking device but a space-making one.

To explain by way of a comparison, at first viewing, Illuminations Series might be said to recall the work of another Vancouver-based photographer, Chris Gergley. In Gergley’s 1998 series Vancouver Apartments (a nod to Ed Ruscha), the artist captured the fading faux-glamour of 80 different (but essentially the same) lobbies of middle-class apartment buildings built mostly between 1950 and 1970.

Like Nizam, Gergley’s images are not nostalgic but nonetheless speak to loss: a collective loss in the ability to believe the promises that seemed, for a time at least, to be lodged within that domesticated modernism.

Dated and threadbare, as in Gergley’s sites, or emptied and awaiting destruction, as in Nizam’s, we might view such venues as places akin to Walter Benjamin’s “monuments of the bourgeoisie,” which the German critic once described to be recognizable “as ruins even before they have crumbled.”

However, while Gergley collapses these spaces into a flattened image emphasized by the relentlessly frontal viewpoint through the buildings’ glass-doored entrances—variants of a typology—Nizam’s interventions, while only discernible through the camera, open up the two-dimensional picture into a resounding (and confounding) sculptural space.

He achieves this with a high awareness of the way many of us, following the influence of writers like Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag, have come to understand how photographs operate.

As Barthes offered in one famous passage, a photograph is “in no way a presence…Its reality is that of the having-been-there.” For him, the analog photograph is always a memorial, “an umbilical cord connecting us to what we have loved and lost, to what is gone because we failed to save it, or to what might have been, but now will never be.”

In this way, Nizam’s abandoned domiciles already recede into the past. (We can rest assured that by our time of viewing, the depicted structures are no longer standing.) But this elegiac retreat is halted by, and caught in tension with, the opening of another, purely ahistorical, geometric space: the one described by his light forms.

Nizam articulates this as the moment when “a work unhinges itself from the site” to expand outward, I would argue, both optically and metaphorically. Milan-based photographer Luisa Lambri, speaking of her practice, expresses a similar notion. She tells interviewer Shino Kuraishi, “What actually interests me most is the idea of loss. I’m not thinking of a sense of nostalgia, nor of a fascination for the past which is trapped in ruins or architecture. To me, loss is that specific moment in which a place turns into space. Places we feel attached to can turn into pure abstract and geometrical grids, whereas the most immaculate and aseptic space changes into ‘place’ as soon as it is invested by desire.”

Perhaps we need to feel that these sites, as “places,” are already lost to us before they can be opened out into the possibility of abstract space. In this way, rather than falling into a lamentation of dereliction (manifest in the category of contemporary photography cliché unfortunately termed “ruin porn”), Nizam’s images are a quiet refusal of it.

The connection between the apparatus of photography and architectural space is obvious for Nizam: “When window boardings are placed over an abandoned structure its fate is sealed and it becomes entombed,” he has noted. “It becomes like an object of death, a negative space, or a dark room…Perforations that puncture through the structure let light inside in a way that becomes image-forming.”

Nizam’s current work with light evolved largely from his 2012 investigations of apertures, which led the artist to drill holes into the walls of his studio to transform the room into a camera obscura. An empty room is, of course, like the inside of a camera. Often, as Nizam has told me, his process would involve removing sections of drywall in order to place the drill hole, or aperture, more precisely. The debris produced through this process would stir drywall dust into a suspended haze. Under these conditions, Nizam observed the way that light entering through the aperture materialized into an illuminated beam, which led him to consider that an aperture might not only focus an image into visibility but could also focus light into a form.

The next step posed a logical question for Nizam: how could he manipulate an aperture further so that it shaped light into something deliberately sculptural? It was a question that led to the above-mentioned Shard of Light, where Nizam expanded the aperture from a drill hole to a structural cut, “transforming the readymade container of the empty house into a helioscopic device staged to capture and shape light.”

Nizam’s puncture holes and incisions have drawn comparison to those of Gordon Matta-Clark, whose “anarchitecture” of the 1970s—performative works created by cutting and sawing sections out of derelict buildings—were, like Nizam’s, ephemeral and unrepeatable. Indeed, the gigantic ovoid cut from the facade of an abandoned industrial depot on the Hudson River in one of Matta-Clark’s later and most spectacular works, Day’s End(1975), was once described by urban-studies professor Tom McDonough as a massive aperture, “a surrogate projector lens, a vastly enlarged duplicate of the camera the artist himself held while filming the space.”

However, a more compelling comparison might be the work of one of Matta-Clark’s contemporaries in New York, experimental filmmaker Anthony McCall. In the most renowned of McCall’s works, Line Describing a Cone (1973), the projector beam forms a cone of light from the particulate matter and smoke suspended in the air. Without a projected image on which to focus, the audience’s gaze is instead directed toward the beam of light itself. The film thus carved, literally, a volume in space.

As in McCall’s works, Nizam’s light takes on a material presence, manifesting a sculptural space that presents the observer with a captivating spectacle and an analytical experience of form made visible only through the camera. But these sculptural spaces are aloof. They cannot be occupied; they remain in the realm of the imaginary, the theoretical: untethered to and unconcerned by the sentient bodies that regard them.

Nizam’s most recent work troubles the hermeticism of this impossible space. He forays into actual sculpture that occupies the same physical realm as its audience and relies upon the audience’s contingent, embodied regard.

In Vanishing Point (2015), for example, Nizam takes a series of aged door frames gleaned from emptied buildings of a previous project and paints them a flat theatrical black. The frames are reassembled so as to fit, staggered backwards, one inside the other. They diminish in dimensions until the vertical casings are close enough together to allow only the narrowest band of light to funnel through the form—an aperture of sorts. Tapestry (2015) presents an unassuming section of found chain-link fencing cut from its supports and exhibited horizontally upon the floor. Unexceptional from most vantage points, the metal mesh suddenly flashes up as an undulating sea of iridescence when approached from a particular angle, or when set alight with the flash of a camera phone (it has been coated with the same reflective material as the elements in his pictures). With these works Nizam has begun to consider the body, one might argue, as another photographic apparatus.

I ask the artist where his work might go next. Nizam answers by pulling out his iPhone. He shows me a rough video shot in an urban alley with a curtain of steam venting from a building’s ductwork. For a brief moment, the steam materializes the glowing, raking sunlight into nearly graspable matter. It is a found light sculpture—an entirely serendipitous “solid light film” that we have all no doubt witnessed at one point or another. It is Nizam’s way of telling me that the photo/graphe is all around us and that the world gathers itself into form through it.

Kimberly Phillips is a writer, curator and educator, as well as director/curator of Access Gallery, an artist-run centre in Vancouver.

This is an article from the Spring 2016 print issue of Canadian Art, available on newsstands until June 14.