There are those of us who will be drawn to fun fur no matter what its shape or form. It is snuggly and affordable, and it makes a bold, satiric fashion statement when worn with flair. It’s the perfect medium to explore vulnerability and power, and Allyson Mitchell uses it well.

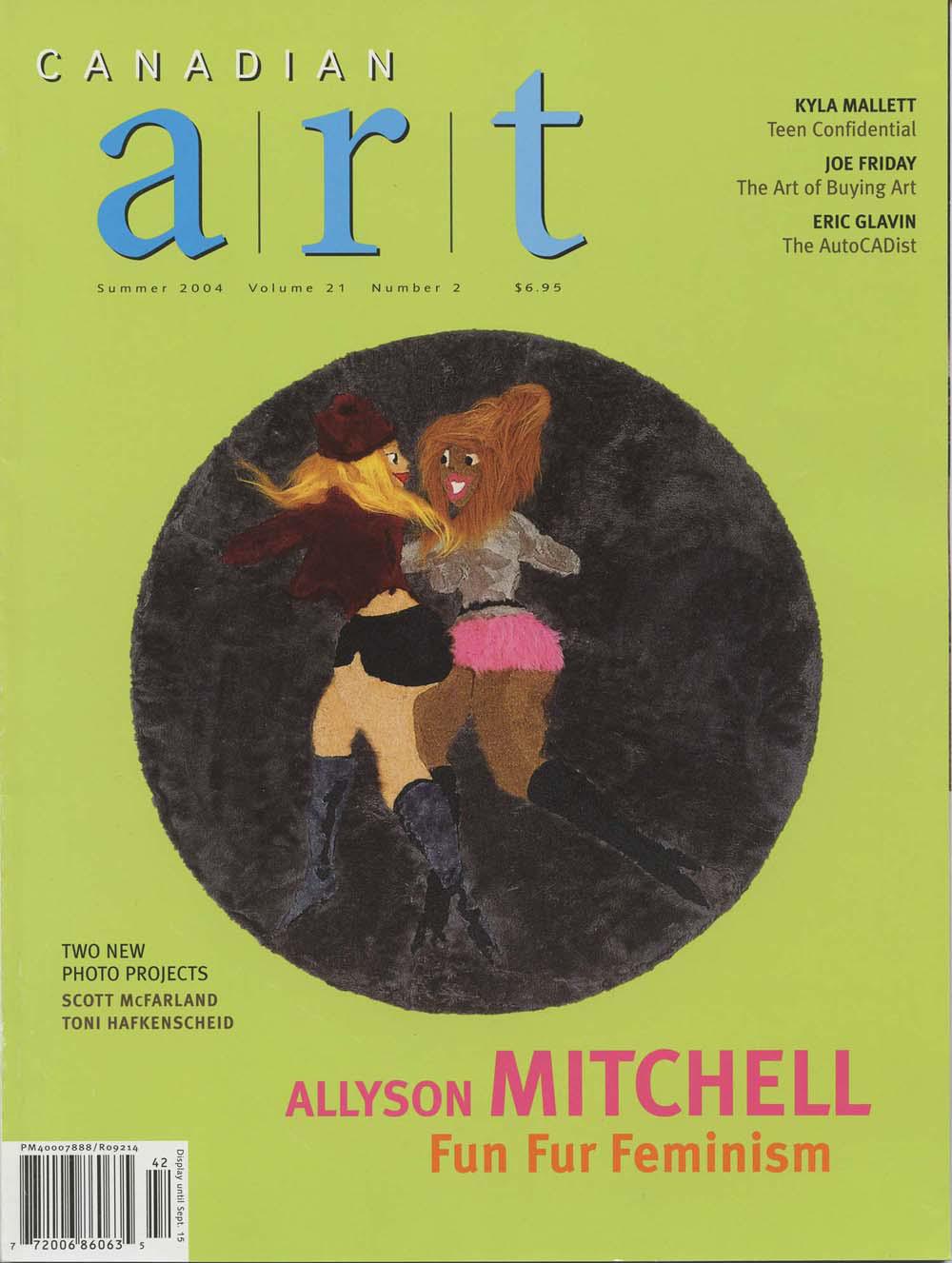

In her recent exhibition “The Fluff Stands Alone,” Mitchell presented an impressive collection of nudes in a series of wall hangings and bedspreads that reinvent the women of Playboy cartoons as fuzzy, happy, flocked and fun-furred beasts. Fluffer Nutter depicts an almost maniacally happy-looking woman prancing on a bed with a twinkle in her eye and bosoms to make your eyes pop out—boi-oi-oing! Crush is the crowd-pleaser, a gigantic orange crushed-velvet bedspread with a lovely orange lady embedded in the nap, her hair a 3-D sprig of tawny fur that begs to be stroked. The more sedate Neapolitan Sunset, depicting a curvaceous figure under a vibrant sky, is another favourite. I resisted the temptation to rub my face on the art, but it was a struggle.

There is tension in the work. Its sensuality is extreme, and it is always challenging when sex rears its head in public places. Nudes are nothing new, of course, but Mitchell’s oddly familiar furry ones provoke a Freudian stirring that feels just a bit dirty, as though any minute your mother might pop up and slap your hand away from down there.

Mitchell first laid eyes on her source material in the Twentieth Anniversary Playboy Cartoon Album while babysitting as a teenager. The sometimes luscious and chunky female forms made more of an impression than the creepy lines of text underneath. She says, “Somehow a microchip in my brain got coded with the information that this can be hot.”

Connecting with these old cartoons again within her ongoing collection of images of large women, Mitchell decided to reclaim this experience. The women in “The Fluff Stands Alone” have bigger waists and a more commanding presence than their Playboy predecessors. Some of them are brown-skinned. There is joy on their bright-eyed faces. These happy, rounded female forms come close to being a tired trope of the iconography of goddess worship, but the work is saved from simple-minded celebration of femininity by Mitchell’s unique and challenging nod to the dark side. The work carries undertones of oppression, both in its source material and in the labour-intensive extremity of its detailed colour and design. It doesn’t deny an uncomfortable intertwining of human sexuality with human emotional pain.

Mitchell is an expert in the politics of body shape. She is currently writing her Ph.D. thesis on a feminist theory of body geography, studying the ways in which our body image shifts in different contexts. Someone who is “under home surveillance about dieting,” as Allyson puts it, might feel too large in her living room, yet may feel sexy in the relative anonymity of public space. Someone else who is celebrated at home may flourish in that intimate setting, but feel self-conscious on the streetcar. Pretty Porky and Pissed Off is a fat-activist performance troupe of which Mitchell is a founding member. Their pink, sugary HTML site includes the following statement:

By coming out as fat we acknowledge our bodies as normal, acceptable, even worth celebrating. Ultimately, fat acceptance is for everyBODY. Fat hatred is a power system in which we are all losers by various degrees. Where fat is feared everyBODY will live in fear of becoming fat, experiencing body hatred and insecurity. Fat acceptance is a deep and lasting acceptance of our bodies whatever our size.

However, self-acceptance does not come, or last, without personal struggle. Mitchell’s art is balanced in a precarious place between fun and pain. For five years, with Lex Vaughan, she was part of the duo Bucky and Fluff. Together, they hosted craft parties, attended zine fairs, adopted a quantity-over-quality approach and mounted friendly shows full of small, affordable art objects made from sequins, macramé, glitter glue, paint-by-numbers and plastic toys. Now that the team has disbanded, Mitchell continues the craft/kitsch aesthetic on her own.

This blurring of boundaries between art and craft is intentional. Knocking high art off its pedestal, Mitchell favours accessibility over authority. Recently she opened her studio to public view in the alternative design show “Come Up To My Room” at the Gladstone Hotel in Toronto. The space is an overstimulating jumble of toys, collectibles, plastic flowers, tiny artworks that look like knick-knacks, tiny knick-knacks that look like art, books, zines, cushions and personal belongings.

“Inviting people into my studio is like letting them walk through my diary,” she says. Some works, at first glance friendly geegaws, are painfully emotional‘little paintings of sad, big-eyed children bordered with ambiguous, sometimes frightening phrases such as “Dad, you’re crazy” and “Mom, that’s mean.”

“Sometimes I feel like I am playing a dangerous game,” Mitchell says. “The emotional content in my work can be quite heavy. People come to it with different levels of understanding in their own politics, and my work will trigger them. You can’t put parameters on emotional connections to artworks, but sometimes I feel like saying, âI’m not saved myself, I can’t save you!’…Why do I do it? Because it feels authentic; the real deal. This is me, unmediated. If people get that, then I feel less crazy.”

The list of art influences she confesses to is revealing: girl-power do-it-yourself filmmaker Sadie Benning; kick-ass zine-style illustrator Fiona Smyth; macramé-making, resin-casting duo Fastwürms; Margaret Keane, who made the infamous, saccharine “Big Eye” paintings of children and animals, to name a few. The most interesting is Henry Darger, the outsider artist who worked as a janitor in Chicago and lived in a boarding house until his death in 1972, when his secret, terrifying, epic body of work was discovered. The Story of the Vivian Girls, in what is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion is Darger’s massive collection of images and writing. In it, oddly Victorian little girls are rendered in pastoral environments where complex scenes of violent sexuality, dismemberment and death occur. It is both disturbing and fitting that Mitchell would cite Darger as an influence, and it indicates her determination to face head-on the horrors that the psyche has to offer.

In some circles, Mitchell is best known for her film work. She is currently collaborating with friend and fellow artist Christina Zeidler under the collective name Freeshow Seymour. Of all her work, Mitchell’s films may best show the dichotomy between kittenish play and wrenching introspection. My Life in 5 Minutes tells the story of Allyson Mitchell through a montage of family snapshots and sad little paintings of big-eyed girls illustrating woeful sentiments such as “pinchy sister,” “harsh words” and “bulimia.” The snapshots of her as a child are manipulated and crudely animated so that the eyes grow large and cartoonish in a manner that is much more spooky and mask-like than cute. The film jogs along to a plaintive little song, sung in a small, girlish voice, about events such as achieving Brownie badges, playing Little House on the Prairie games, self-loathing, secret eating and abject adolescent misery. By the end, however, Allyson is an out-lesbian adult, posing with her friends and clearly enjoying her body. There is acute pain woven through the entire tale, yet at the same time it is a typical, even wholesome, coming-of-age story.

Mitchell is “just folks.” She opens a door with her low-art, craft aesthetic, her direct manner, her welcoming subjects and fuzzy, yummy imagery. And she invites us to go to painful places, to purge, reclaim and ultimately enjoy ourselves.

From the Summer 2004 issue of Canadian Art.