In 1981, Peter Galassi, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, presented an exhibition entitled “Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography.” In the accompanying publication, Galassi articulated his theory for which the paintings and photographs in the exhibition were intended as supporting evidence and illustration. Rejecting the habitually recycled narrative that characterizes photography’s invention as a predominantly technical or scientific achievement, Galassi argued for an appreciation of photography as a legitimate product and continuation of European pictorial tradition.

Painted and sketched studies by Constable, Valenciennes, Købke and other artists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were presented as examples of a proto-photographic vision. Chiefly landscapes, these works favour the everyday over the grand themes and subjects of history painting. With this new Realism and naturalism the model of vision evolved away from the synthetic toward the analytic. Galassi contrasts paintings by Uccello and Degas to illustrate the move from a predetermined Cartesian perspectival field in which the artist constructs a scene or drama to the notion of a pre-existent material, real world from which the artist might select a particular view. This transition produces pictorial effects that have long since been characterized as “photographic.” This new “syntax of immediate and synoptic perceptions and discontinuous forms,” as Galassi termed it, has been popularly recognized as photography’s influence upon Impressionism. However he also provides generous evidence that Impressionism’s abrupt cropping and other photographic effects appear in handmade pictures well before Impressionism and the invention of photography.

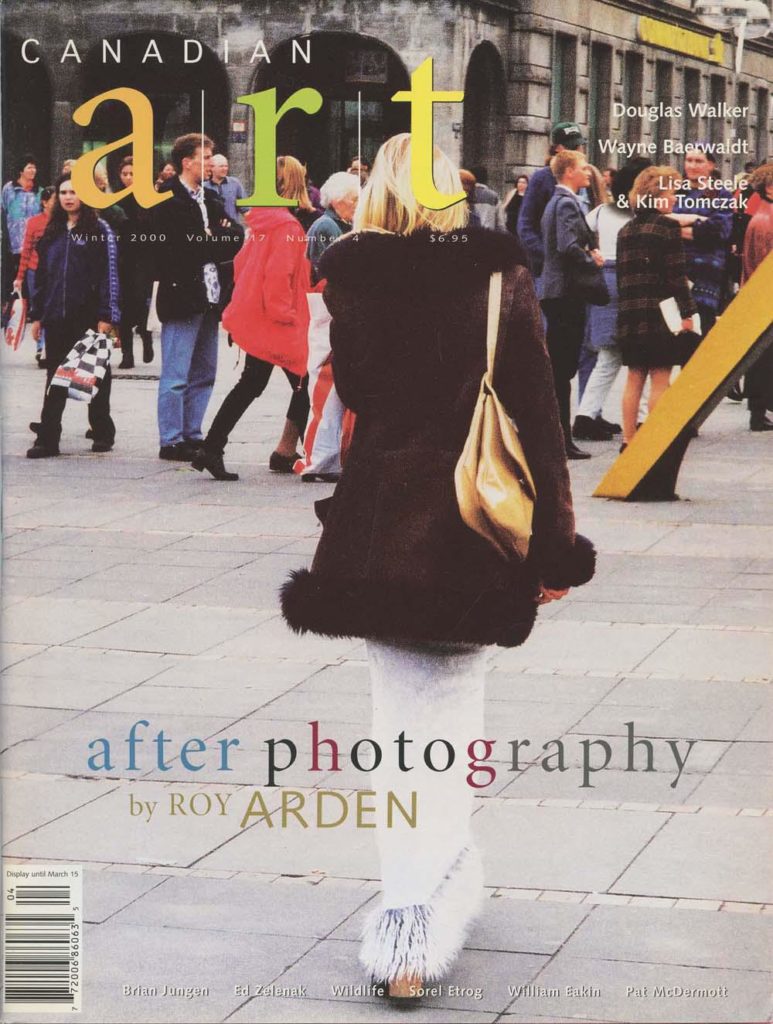

So begins our Winter 2000 cover story. To keep reading, view a PDF of the entire article.