I could recite Christopher Pratt’s order perfectly: 12-grain bagel, double-toasted, plain cream cheese and strawberry jam on the side, a medium dark-roast coffee with a splash of milk. Not only did he order the same thing every time, but I had also been reading those words in his travel journals for years. I ordered the same. We unwrapped our meal hours later, parked at his usual stop along the isolated Burgeo Highway. I turned my sound recorder off. “Christopher,” I said, “I hated you before I met you.”

We were on the third day of a week-long road trip across Newfoundland, visiting the places he has painted. I had known him for five years at that point, introduced to him when I was assigned as the curator for his retrospective at the Rooms. “I was angry at you for hurting Mary,” I told him.

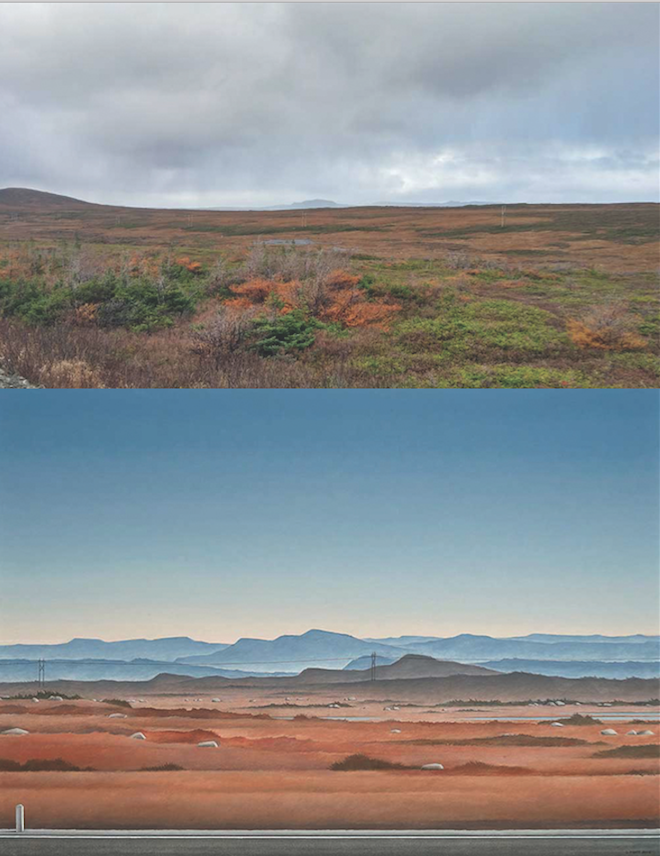

Top: Christopher Pratt re-enacting Sunset at Squid Cove near where he imagined the site would be, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Sunset at Squid Cove, 2004. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

Top: Christopher Pratt re-enacting Sunset at Squid Cove near where he imagined the site would be, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Sunset at Squid Cove, 2004. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

I was speaking, of course, about Mary Pratt, his former wife, a renowned artist in her own right, and a woman who didn’t need me to speak on her behalf. When I was assigned to his show, I was already co-curating her nationally touring retrospective and, later, her exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada. I shifted almost daily from one house to the other, working with each artist on their exhibitions, making it clear from the start that I would always maintain professional distance from their personal relationship. Five years later, to reveal my true feelings to one of Canada’s most respected painters was to admit a failure—an initial bias. It was also a gesture of trust.

“So you turned that thing off for your confession?” He laughed, and sipped from his now-cold coffee (he prefers it cold). “I’ve made mistakes. I have been selfish, and sometimes nasty. I know this and I regret it. But I do not regret the experiences that my choices have brought me.”

In truth, that’s not exactly what he said. I will never accurately remember the conversation, and I regret that. (“That’s the nature of regret; it happens in retrospect,” Pratt told me when he reviewed this article prior to publication. “Seems to me that you’ve captured the truth of what was said. I only have one correction—you have written ‘cruel.’ It should be ‘nasty.’”)

The conversation lasted for an hour that day, an 81-year-old man and a 34-year-old woman talking like old friends about the complexity of relationships. As we spoke, we looked out to the Blue Hills of Couteau. I could see that the hills, as he had painted them, did not exist.

Top: Looking out to the Blue Hills of Couteau, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Burgeo Road: The Blue Hills of Couteau, 2014. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

Top: Looking out to the Blue Hills of Couteau, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Burgeo Road: The Blue Hills of Couteau, 2014. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

And yet, by turning off that microphone, I invoked an inherent question: when should something be on the record? The relationship between a curator and an artist is privileged. It invites access to an artist that few enjoy, and therefore means being aware of one’s role within that process. A good curator will be a supportive presence in the public exhibition space, providing intelligent insight about an artist’s practice. A good curator will gently navigate a respect for an artist’s privacy with the visitor’s desire for personal stories.

A good curatorial text, for example, would not be the place to share the moment with Pratt that affected me the most. We were sitting in a hunting lodge on the fourth day of the trip, watching bad television. At one point, I looked over and saw a man—tired, comfortable, completely himself. The honour and the sadness of it jolted me. Rarely, I realized, had I experienced that with anyone, and never before with an artist. “Have you seen this show?” he asked me, highlighting a program in the channel guide as he scrolled through. “No,” I replied. “Good,” he said, “Don’t.”

Pratt’s 2015 retrospective at the Rooms focused on his extensive travels of his home, Newfoundland. Over the past 15 years in particular, he has continually returned to sites that hold personal importance for him. He documents these journeys in what he calls “car books”—lined notebooks where he describes weather conditions, the feeling of sunlight on his hand, what he has eaten (the same thing every day), moose sightings, conversations with travel companions and memories of family trips as a young man. These journals were included in the show, along with some of the mementos that he collects—stones, sand, strangely shaped twigs―all identified with their place of origin. A visit to his studio will undoubtedly involve a tour of the objects’ stories, pulled from the same places he paints. I wanted to share that experience with others.

Top: Along Route 430, on the way to St. Anthony, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Solstice Drive to St. Anthony, 2008. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

Top: Along Route 430, on the way to St. Anthony, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Solstice Drive to St. Anthony, 2008. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

Ultimately, my intention was to reveal how his paintings are a highly personal autobiography. They combine a respect for the language of painting with an embodiment of the privacy of memory. I wanted to show how, in each work, Pratt is the observer. He positions the viewer where he stands, as he looks at places that hold personal significance, remembering.

A road trip with Pratt will reveal that Benoit’s Cove should be seen at night. If you travel with him, he will point out the one window of the Deer Lake power station that is smaller than the others. He will remark upon Venus’s arrival in the sky, and how the headlights open the road ahead as darkness slaps shut behind. He will tell you, again and again, that Newfoundland does not exist exactly as he portrays it. “I make paintings about, not of, a place,” he will say. And yet, when a familiar structure is missing, he will search for it. When a favourite tree appears to be on the verge of death, he will mourn it.

We drove approximately 3,400 kilometres: St. John’s to Grand Falls–Windsor, to Buchans, to Corner Brook, to Benoit’s Cove, down the Burgeo Road, up the Great Northern Peninsula, into Gros Morne National Park, through Stephenville, around the Port au Port Peninsula. Moving through a beautiful and varied landscape, philosophical discussions transitioned to puns. I learned about the history of this province—its dying industries, its politics, its infrastructure, its changing wildlife. I learned about his first love, his family, his studies with Alex Colville, his business relationship with Mira Godard. I listened to him recite the name of each place we passed while predicting the next. Each had a story.

Top: Original site for Trout River: Little Otto, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Trout River: Little Otto, 2013. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

Top: Original site for Trout River: Little Otto, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Trout River: Little Otto, 2013. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

I held the microphone between us the whole time. I would turn it off during rare moments of silence, to restart halfway through a particularly poignant statement. “Christopher,” I told him, “you need to tell me when you’re about to say something meaningful!” I began to scrawl quotes on Tim Hortons napkins, storing them between the pages of the catalogues piled on my lap whenever my notebook was out of reach.

When we arrived at a place he had painted, I would exit the car with a catalogue and a camera, comparing the original site with the result. To my annoyance, he would turn his camera on me. Pratt has photographed me trudging through snowy seaweed to get the right angle, circling a lighthouse while soaked with October rain, and struggling through a deep ditch with my hair blown upward. “Ha! That’s a great one,” he said of a particularly terrible photo of me getting into the car, “You look happy.”

We would then discuss the difference between the reality in front of us and the painting he had created. In some cases, his adjustment was as small as a window removed for the sake of balance. In others, he would alter entire colour schemes. Sometimes, a building never existed in the first place.

“But why do you choose such ugly buildings, Christopher?” I asked him once.

“It’s not about beauty,” he replied, “It’s about presence.”

Top: Original site for Ingornachoix Bay: Long Shed, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Ingornachoix Bay: Long Shed, 2007. Oil on paper on board. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

Top: Original site for Ingornachoix Bay: Long Shed, October 2016. Bottom: Christopher Pratt, Ingornachoix Bay: Long Shed, 2007. Oil on paper on board. Courtesy Mira Godard Gallery.

At dinner on the first night, he told me of a dream he had when he was seven years old. In it, he walked down a road knowing that it led to the end of the world. The road dropped off abruptly, and he stood looking out to a vast emptiness.

I remember thinking of that dream on our sixth day, as we travelled a long, straight needle of land on the Port au Port Peninsula. I had asked him to take us to a place neither of us had been before, out of personal curiosity. For 20 minutes, the recorder documents the sound of the vehicle jostling through potholes and puddles. About five minutes in, you hear Pratt: “This is, by far, the worst road I’ve been on.” Some 10 minutes in, you hear my tentative question: “Maybe we should turn back?” He keeps driving.

We land at Blue Beach—a series of small houses, a government wharf, a rocky shore and soft grass. You hear us leaving the car, giddy with success. We ascend a small hill to a field with an encompassing view of the land, sharpening to a pinpoint in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. You can hear how happy we are to be there. “As the old saying goes,” Pratt tells me, “‘It may not be the end of the earth, but you can see it from here!’” And, with that, I turn off the recorder.

I recall that, soon after, I found a beautiful, fossilized cluster of small shells to bring home. He picked up a brick: “To remember this place,” he said.

Addendum

My road trip with Pratt followed that of Josée Drouin-Brisebois, senior curator of contemporary art at the National Gallery of Canada, and the curator of his national tour in 2005. Josée recognized the importance of travel for Pratt’s artistic practice, and proposed their trip soon after his separation from Jeanette, his second wife and longtime travel companion. It was an act that would inspire a series of trips with family, colleagues and friends.

Artist at breakfast, Corner Brook, October 2016.

Artist at breakfast, Corner Brook, October 2016.

When Drouin-Brisebois and I compared stories in a coffee shop months after my trip, I realized that our experiences were fundamentally different—despite a similar itinerary and the same, unplanned purchase of an orange hat emblazoned with the words “HUNTING EXPERT” before we each went up the Great Northern Peninsula. They would have breakfast at 7 a.m., for example, arriving and departing with military precision. He and I would meet at 8-ish. I was always late, but he was always later. He would take his handful of vitamins, listing them off to amuse me as I quietly drank my coffee. When we felt like it, we went to the car. These differences seem inconsequential, but they surprised me. There are very few people who are more religious about their routine than Pratt, and I thought I knew it well.

Drouin-Brisebois and I then broached the topic of his art. “I believe his work is political,” she said, “It describes Newfoundland changing over time.”

“I disagree,” I replied, “His work is consciously apolitical. It embodies the personal, autobiographical experience of a series of places he knows well.”

“You have one piece of fabric, from which you make a pair of pants and a shirt,” Pratt told me when I described the conversation to him later. “They are two different items of clothing, each cut from the same cloth. Similarly, the form of my answers depended on the form of the particular questions you each asked me. Both answers are true.”

Mireille Eagan is curator of contemporary art at the Rooms in St. John’s.

Christopher Pratt driving by the Deer Lake power station, October 2016.

Christopher Pratt driving by the Deer Lake power station, October 2016.