So what do you do on a rainy Sunday night in a wet tent in Algonquin Park when the fire wont start and the sleeping bags are damp and the red squirrel wont eat out of your hand? You talk about ping-pong and Tom Thomson and how art is a conversation not a thesis and how scenery means submission and why, when it comes right down to it, Rosedale (Torontos Rosedale, pretty little Rosedale, rich little Rosedale, all birthday cakes and water ice) is enough is enough is enough.

Canisbay Lake, Algonquin Park, Camp Site 59 (one of many designed for sissy drive-by campers like us), Sunday, June 16, 2002. We have selected this spot because it is guaranteed by the Parks reservations office to be both a radio-free zone and a pet-free zone. Site 59 is now temporary home to me and fledgling artist Peter and fledgling interior designer Michael and a brand new rental car we imagine is called a Seabreeze, as if it had been named by the people who name aftershaves. We are here because I have just seen the Tom Thomson show at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa (it will travel, over the next year and a half, to Vancouver, Quebec City, Toronto and Winnipeg) and I have conceived this little homage whereby we will sleep in tents and have our fill of jack pines and feel the west wind on our faces and linger meditatively at Canoe Lake, in whose quiet summer waters Tom Thomson drowned on Sunday, July 8, 1917. Some say accident. Some say suicide. Some say murder. All we know for sure is that when they found his decomposing body eight days later, there was a bruise on his temple and a length of fishing line wrapped around one ankle, and his watch had stopped at 12:14. He would have celebrated his 40th birthday just a few weeks later. He had been a serious painter for no more than four years. And he would become a legend in less time than that.

He became Natures child, the untutored innocent whose only school was Nature, practically an Indian in his command of canoe and camp and fishing line, at one in his death with the boys who were laying down their lives in the killing fields of Europethey for deliverance from the Hun, he for the freeing of Canadian art from the strictures and patterns and obsessions of our European betters.

Every time there is a Thomson show, every time there is a Thomson book, these myths are laid to rest one more time. Harold Town and David Silcox did so in their book Tom Thomson: The Silence and the Storm, first published in 1977. The organizers of the current show do a splendid and definitive job, acknowledging an apprenticeship in drawing and calligraphy in Seattle, tracing Thomsons developing career as an accomplished graphic designer in bustling early-20th-century Toronto, showing how he learned from his friendships with the more artistically mature, travelled and knowledgeable painters who would, two years after Thomsons death, join together as the Group of Seven and, as every schoolboy knows, raise high the banner of a distinctive style of Canadian painting.

Yet here we are, tenting in the rain in the very heart of the myth, trying it on for size like naive schoolboys acting out the exploits of their favourite action hero, somehow wilfully forgetting that one of the crueller kindnesses of any art is to give us a past without a historyin this case a past we read in Thomsons art that is all forest primeval and pristine lakes and campfires and roughing it and red squirrels who have not been so tamed by the kindnesses of generations that they will almost eat from your hand. We seem to crave that past, my young friends even more than I, though even a glancing acquaintance with its history will tell us that the Algonquin Park we are in tonight is arguably wilder and more pristine than the freshly logged, much advertised and much touristed Algonquin Park of Thomsons day. We might call our need for that imaginary past our need for the flight from Rosedale, from an excess of cultivation and refinement, from what men in particular see as civilization carried to an almost feminine degree of delicacy. We sense Tom Thomsons aversion in the only interesting words he ever set to paper (his surviving letters deal almost exclusively with practical matters like banking problems and camping difficulties). The truly luscious irony is not only that one can never escape Rosedale, that it is always latent within us, but that Thomson, in the jewelled and controlled savagery of his greatest works, made of Algonquin Park what we might call his own private Rosedale.

In a letter postmarked July 8, 1914, Thomson writes to his friend and fellow painter Fred Varley from the comforts of the Georgian Bay home of his friend and patron, Dr. James MacCallum. I am leaving here about the end of the week and back to the woods for summer. Am sorry I did not take your advice and stick to camping. This place is getting too much like north Rosedale to suit meall birthday cakes and water ice etc.

The moment I read that, I knew what Tom Thomson was like. I grew up with men like that, in a remote pulp-mill town north of Superior. They were quiet men, of unfailing courtesy, almost chivalrous in their attitudes to women. They were never rowdy. They did not talk much. Strong, silent types would be the cliché, though that phrase does not acknowledge their unobtrusive talents and sometimes unlikely accomplishments. Boys loved them for it, and stood in awe of them and often learned from them for they did not hoard what they knew. Many were, like Thomson, accomplished fishermen, though Im guessing few were, like Thomson, devotees of The Compleat Angler, Izaak Waltons 17th-century meditation on the contemplative nature of that sport. None were painters.

But then Thomson was the citified version. Most of his adult life had been spent in urban centres. He had gone to business school in Chatham, Ontario. He was an accomplished illustrator working at a prestigious firm in downtown Toronto. He made his first trip to Algonquin Park in 1912, only five years before he died. He went as frequently as he could after that, and knew the place in all seasons of the year. Of those trips he created an art which is a conversation about silence, and the impossibility of nature.

But here, tonight, inside a wet tent at pet-free, radio-free Site 59, I am having a conversation with Peter Kingstone, 28, fledgling artist from Toronto, about Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven and why he didnt bother seeing the show that hed driven me all the way to Ottawa to see and his answer is very much been there, done that, bought the mouse pad. In his lifetime those images have been background on everything from greeting cards to calendars to coffee mugs. I dont see why its such a big Canadian deal, he says, and the rain goes drum drum drum on the tent, and I dont feel that wilderness is any large part of my life, and then he jokes that youd never get a sense from a Tom Thomson painting that Algonquin Park is full of mosquitoes but if the rain ever stops for a minute you discover it surely is. And then he concedes that a lot of art he does like has no direct bearing on his life. But this? Its another generations art. I feel it should be hanging in my parents den. I like art that asks political questions but this stuff feels devoid of political questions. I like intelligent work that refers backwards and forwards, that speaks of things outside itself, and the rain is still going drum drum drum on the tent and then theres momentary guiltmaybe Im trying to fight it because Im supposed to like itbut that doesnt last. Ive never stood in front of a landscape painting and said, Wow, thats beautiful. But Im willing to go on top of a hill and say wow. I love looking at scenery. Much more than at painting. Then finally, and this last is the verbal equivalent of drawing the moustache on the Mona Lisa, I want art to bring questions. Tom Thomson has become the answer.

I know the question that Tom Thomson brings for me. He is asking whether nature is possible.

When I was a child growing up in the bush in northern Ontario, one of my primary-school teachers would devote a few hours a week to something like an art class. She would move from desk to desk, laying face down before each child a wallet-sized card. When every child had one, she would give us permission to turn them over (and woe betide the over-eager youngster who couldnt wait). We would see a full-colour reproduction of some famous work of art. Many would be by Thomson or members of the Group of Seven. Others would be by European artists. The former made sense to me. In a town without television, in a house without books or magazines, I had no reason to think that the world was anything but an endless unravelling of the woods and lakes and rocky hills I saw around me. I believed this for a very long time. I did not think the world much peopled. I could not have so expressed it then, but I found the teeming bustle of what I saw of European art as almost offensive. Even their landscapes seemed crowded. Tom Thomson was nature as I knew it then. Tom Thomson was silence as I knew it then.

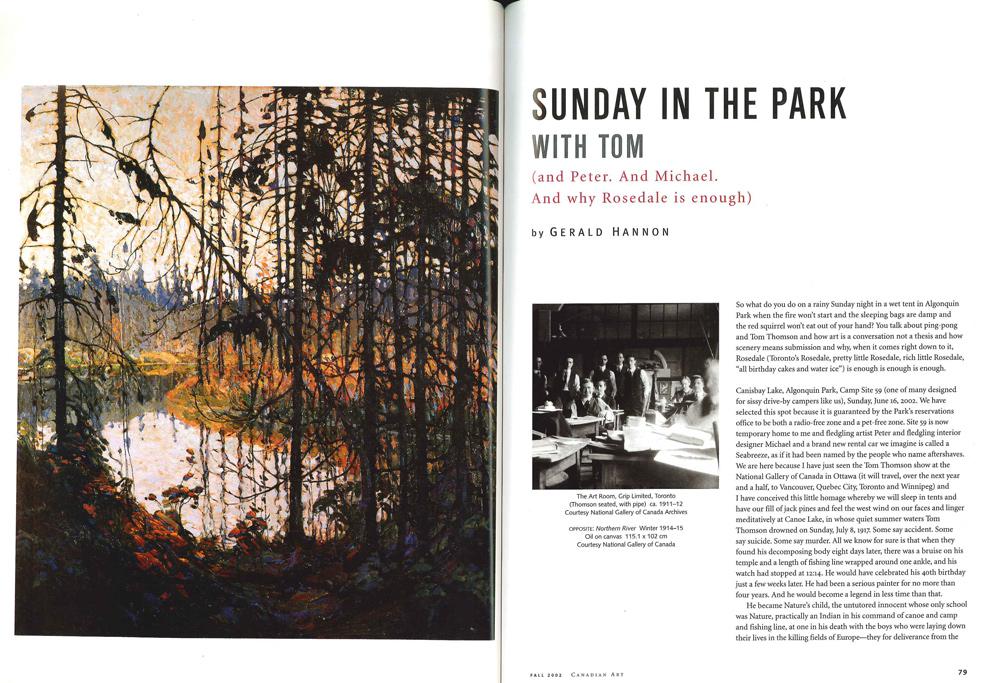

So many of his paintings capture the awful silence of the northern bush. He could make silence visible. In a painting like Northern River, there is no room for soundthe works very flatness and the sobriety of its colours are inimical to anything as impertinent as voice or sigh or birdsong. Even on those rare occasions when there is a human figure present, as in In the Sugar Bush (Shannon Fraser), that figure is so one with the trees and soil and shadows that it is quite as mute. And yet. And yet I have talked of Thomsons work as a kind of conversation about silencea realization I have come to only with this show. The endless tracery of branches in Northern River; the repeating, slithering shadows of In the Sugar Bush linger with us as a kind of whispering, as a hush that is at least pregnant, and when we reach a work like The Tent, painted in the fall of 1915, the startling whiteness of that canvas shelter (surely no bush tent was ever that white), figured and enlivened with the blue and brown shadows of the trees that surround and support it, almost reaches the status of voice. It is impossible for me now to believe that that tent is empty. It hums.

By this time, too, Thomson had freed himself from the prison that is scenery. The pleasures of scenery are drowsy and passivethey lie in your being helpless before it. The pleasures of landscape lie in its being helpless before you. Every successful landscape is a critique of nature, not a celebration of it, an understanding that began to flower in Thomson in 1914, the year in which he began to give evidence of his future talents, according to the shows curator, Charles Hill. Fellow painter A. Y. Jackson described him at work in that pivotal year: No longer handicapped by literal representation, he was transposing, eliminating, designing, experimenting, finding happy colour motives amid tangle and confusion and revelling in paint. By the end of 1915, according to Hill, …he was experimenting in a new way, and the contact with the source motif was not always a prerequisite. A number of sketches dating from this time may have been painted from memory in his Toronto studio rather than in the region of the park.

In Thomson there is the tension between the impulse to paint what he sees and the artists certain knowledge, which became secure in him only in the final years of his life, that nothing he can actually see is worth painting. Out of that tension he made a conversation about the very possibility of nature, a dialogue that crackles in the space between what we know he sees, what we see in his work that no human eye is capable of seeing and what that work will finally teach our frail and human eyes to see. Can one ever come upon a solitary jack pine now without the certain knowledge that it is one step away from dance? Or that the sky behind it sings?

Which brings us back to Rosedale with its dancing and its singing, its birthday cakes and water icea culture in which Thomson may have been temperamentally disinclined to participate but which is increasingly visible in his work as his genius matures. I do not mean that his paintings became merely pretty, or decorative, or calculated not to offend the sensibilities of people who have money. They became stronger, and they became so precisely because they have the backbone that is artifice, the artifice that finds its social expression in the metaphor that is Rosedale. Only the civilized recognize nature. Only the civilized need it. And the only way we have of reaching it truly is through artifice.

Sunday in the Park with Tom. Sunday in the Park in seemingly endless rain, grabbing a moment in the afternoon when rain has turned to mist, walking the edges of a Canoe Lake lined with dozens of overturned rental canoes waiting for visitors waiting for better weather. We cant visit the lakes memorial cairn to Tom Thomsonit is reachable only by water and that we are not about to risk. We see moose later, along the highway, and they are looking contemplative. We follow a carefully marked woodland trail that eventually leads us to a high point of land from which yet another Algonquin lake is visible. It is wearying, finally, all that scenery. We are so powerless before it.

Then back, in gathering dusk and rain, to Site 59. The tents are drenched and water is pooling on the floor inside, but Peter and Michael are determined to spend the night in theirs. Me? I sleep in the car. I have my book of picturesthe beautifully thought-out exhibition catalogue, page after page of Algonquin Park from the eye and hand of Tom Thomson. I can look at them until the light fades on the Algonquin Park outside. I can sit in the front seat in the warm, enveloping dark, caress the metal and plastic trim, smell the new upholstery, hear the rain thunder on the roof. I have my own private Rosedale. I have just what Tom Thomson had.

This is a feature from the Fall 2002 issue of Canadian Art.

Spread from the Fall 2002 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Fall 2002 issue of Canadian Art