Taras Polataiko stops at little in his installations and paintings. In 1992, he immersed himself not only in graphite powder but also in controversy when he imitated an officially commissioned statue of Ramon John Hnatyshyn, Canadas then Governor General, in Saskatoon. The performance, Artist as Politician: In the Shadow of the Monument, set out to ”honour those Ukrainian Canadians who did not become Governor General.” It was Polataiko’s debut as an artistic irritant, an aesthetic agent.

Artist as Politician, however, was simple and safe compared with Cradle (1996). For that project, Polataiko travelled to his native Ukraine ten years after the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown. Being in the area allowed him to pollute himself with contaminated radioactive fallout. The move self-consciously internalized and made literal what the artist Kasimir Malevich once called the “additional element” in art—its infectious, transformative potency. “To me, virus is some hidden element that is always there in any ideology or organized structure,” he explains. “It’s on the margins, it’s like parallel reality. It sleeps and once it awakens, nothing is the same because then the mutation begins… It could be a disease, it could be radioactivity, it could be the painterly space.”

The central element in Cradle, the installation that Polataiko created once he had returned from Ukraine to Saskatoon, was a cast-iron, nickel-plated bathtub into which he drained the equivalent of his full bodily complement of slightly radioactive blood. The radioactivity, Polataiko says, is ”a latent agent and its beyond narration or language. You cant see it, smell it or taste it. But when you become aware of its presence, youre not separated from it any more, so its impossible to be an observer, because you start to change.”

Changing himself and changing us—the observers of his works—is Polataiko’s dangerous and ambitious creed. In ten years as an artist he has produced a body of work that engenders metamorphoses, presenting permeable membranes between life and art, reality and fiction. His installations and paintings demand both a cerebral and a visceral response; they work logically, but are produced through intuition. Where they mirror and challenge social norms, they are also engaged with material formalism. Polataiko wants his art to get into our biological and social systems. He constantly uses his own life in his work, but it is an adopted, mirrored, contaminated “half-life.”

His recent project HIM is a case in point. It began with a meditation on the ancient superstition that the devil’s name could not be spoken for fear of invoking his fearsome presence. For the first installation of the piece, held at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Kiev and at Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Polataiko appropriated the techniques of contemporary forensic profiling. Though the police don’t look for the devil or evil as such, they did allow Polataiko use of a photo-compositor in the gallery for visitors to combine parts of different faces of missing persons. The artist videotaped this process of selection and recombination, then chose the face that received the most attention. This he circulated as a ”wanted” poster for HIM and auditioned would-be look-alikes before selecting a real-life HIM. In the installation, visitors had to go through a maze of large photo-portraits of candidates who believed that they looked like Polataiko’s wanted poster (posted around the city) to arrive at a live video image of the chosen HIM. What they didnt realize was that the incarnation of HIM was behind a wall in a room nearby and could watch them via a surveillance camera. He could respond to their responses and be immediately, menacingly present.

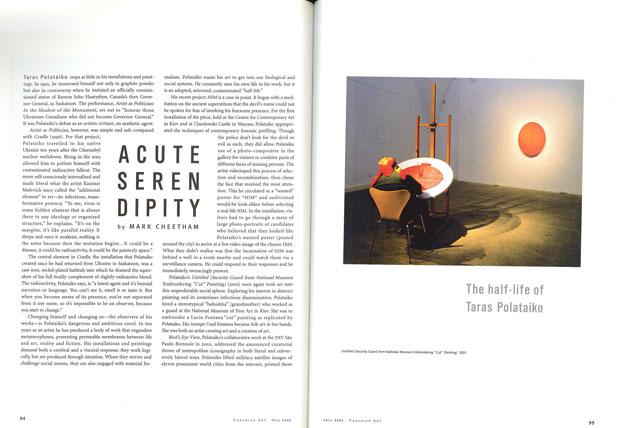

Polataikos Untitled (Security Guard from National Museum Embroidering ”Cut” Painting) (2001) once again took art into this unpredictable social sphere. Exploring his interest in abstract painting and its sometimes infectious dissemination, Polataiko hired a stereotypical ”babushka” (grandmother) who worked as a guard at the National Museum of Fine Art in Kiev. She was to embroider a Lucio Fontana “cut” painting as replicated by Polataiko. His trompe loeil Fontana became folk art in her hands. She was both an artist creating art and a creation of art.

Birds Eye View, Polataiko’s collaborative work at the XXV São Paulo Biennale in 2002, addressed the announced curatorial theme of metropolitan iconography in both literal and subversively lateral ways. Polataiko lifted military satellite images of eleven prominent world cities from the internet, printed them and had them cut into puzzle pieces. He installed eleven large mirrors that would form the supports for the reassembled pictures, then hired two teams of eleven unemployed local residents to ”do” the puzzles. They performed this act of recreation over seven days, accompanied musically by Igor Stravinsky’s Lords Prayer. Although he carefully orchestrated the work, Polataiko nonetheless distanced himself from the process of its authorship. The result broadcast both irony and certainty: people who normally have neither a “birds-eye view” of the world nor a significant role in its development were made the agents of the reconstruction. No one could deny their authorship, but their creative agency (reflected in the mirrors as they worked) seemed less prominent over time, as the “puzzle” of each citys image reasserted itself (covering the mirror).

The artwork also addressed the painterly discourses of abstraction and figuration: detailed satellite photographs of the cities became abstract patterns for a while, much like some of Gerhard Richters paintings and in conscious homage to the German artist’s grisaille, aerial paintings of urban Madrid. The supporting mirrorsanother reference to Richterwere rendered invisible when the puzzles were completed. In the final installation, however, shard-like reflections from the mirrors’ now-submerged surfaces caught the eye. These random ”glares,” as Polataiko calls them, are a reminder once again of the hidden but never absent ”additional element,” of art’s infectious nature.

Two of Polataiko’s recent inventions further this mission to make art that is an infecting, unsettling force on individuals and institutions. They are, however, lighter in approach and implication than most of the earlier work. Dreams, created for an exhibition at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona in early 2003, is, according to Polataiko, a work about boredom. ”How does one make a piece about boredom without being boring?” he asks. ”Art seems to be able to feed easily on provocative things like violence, child eroticism or other well-packaged forms of political incorrectness. One thing art cant tolerate is boredom. Boredom seems to be too radical.”

The Dreams installation is a projection of the repeated inflation and explosion of a balloon, accompanied by a soundtrack of hissing air. Facing the image is a black sofa onto which is projected an image of a cat. Most of the time the cat sleeps, its tail moving slightly. The balloon eventually swells to fill the screen, looking like a red monochrome painting with a shiny glare in the middle. At intervals, the balloon bursts and the startled cat wakes up, looks at the balloon but sees an empty screen and goes back to sleep. Viewers can sit beside the projection and watch the cat, the balloon image and a TV. It shows a loop of associative images: explosions, suspenseful passages from movies, sequences of breastfeeding, breast implant surgery and a remix of domestic TV and video footage. The remix includes Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc and Vampyr, a pornographers’ annual convention, a Learning Channel show about libido with close-ups of strippers’ breasts and male gazes, safety airbags in action during a test car crash, Andrei Tarkovsky’s films and manipulated footage of Alice in Wonderland. Like the filling balloon, these cultural reverberations and dramatic aural interruptions constitute both a tedious rhythm and an unpredictable element of anticipation and surprise. People are affected; the cat—an incarnation of covert surveillance—appears to sleep.

Polataiko’s art avoids stasis, even when it purports to be about boredom. Nothing is allowed to be what it might seem to be. His early Glare paintings, for example, look like Malevich’s Suprematism but are in fact paintings of photographs of Malevichs paintings. Polataiko’s Cuts look to be seductive painted reproductions of Lucio Fontanas famous Attese, but where Fontana slashed his canvases and moved into the “void,” Polataiko gives us only semblance and surface. Polataiko’s Humidity, an installation of variably sized and, from a distance, apparently monochromatic paintings of water drops (shown at Sable-Castelli Gallery in Toronto in the spring of 2003), seems to be nothing more than a decorative series of organically shaped canvases. Polataiko doesnt insist on the water imagery: he sees them as abstract. In either case, the painterly skill involved in making these flat, oddly shaped canvases that declare their three-dimensional, dynamic existence and appear to be wet is manifest. Mounted on the gallery wall, the paintings suggest other implications to the attentive viewer. What is all this humidity doing in a place where too much water would be a disaster? As with the babushka’s labour or the relationship between anonymity and authorship in the makeup of cities, Polataiko again reveals something crucial that is otherwise normally hidden in our existence. In each case he has deployed the ”additional element” to critical effect, redeploying known objects and institutions through an infectious, transformative refraction.

If transformation is a key to Polataiko’s art, the idea applies equally to the artist himself. Beginning with his immigration to Canada, he has constantly put himself in vulnerable places, both physically and emotionally. His paintings require a ridiculous amount of labour: six straight months were spent in his Saskatoon studio creating the Humidity series alone. His installationsespecially those involving human subjectsdemand an impresarios energy and patience. Perhaps his most constant theme is the confusing pseudo-revelation of identity through art. I work from many places, he says disarmingly. On the other hand, Polataiko has also become the quintessential Canadian artist, working locally and regionally to considerable acclaim and with a growing international profile. He has the conviction never to let things remain what they seem to be.

A feature from the Fall 2003 issue of Canadian Art