“Aye Captain, the Indians canna take her.”

Forgive my paraphrasing of the above Star Trek idiom—but that’s where it started for many of us, both Native and non-Native. Those cold snowy winter nights on the reserve with an equally snowy television channel showing us that there was indeed life off the reserve, and quite possibly, in different solar systems.

That iconic show—plus The Six Million Dollar Man, Space: 1999 and a myriad of other sci-fi classic (and not so classic) television series—showed my generation what the future could potentially hold. Add to that Star Wars, Alien, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and the plethora of classic sci-fi movies that played in the local theatre, and I was sold.

Soon, I discovered the written works of authors like H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, John Wyndham and John W. Campbell, devouring books and short stories by the bushels. Then came Heinlein, Asimov, Bradbury, Clarke…and the list continues. The authors got newer as I got older. But I was sold. Since then, I’ve loved science fiction—or speculative fiction, for the more refined.

More years passed, and somehow along the way, I became a writer. I wrote many things, primarily but not limited to plays, and the occasional novel or collection of short stories. But always, hiding in the back of my mind, I longed to write something that basically did not as yet exist. A genre that in itself was considered practically an oxymoron.

When I started writing, Native science fiction was, by definition, a contradiction in terms. By that I mean Native literature was generally believed to consist of three avenues of literary exploration: victim narratives, historical themes, or side effects of what I call Post-Contact Stress Disorder.

It seemed, as a result, that Native people and technology did not go together. Nor did spaceships, or aliens or even science in general stop in at First Nations communities looking for cheap gas and cigarettes. Instead, literarily speaking, we just travelled in canoes, hunted buffalo, had alcohol problems and suffered a number of other social ailments.

In those days, science fiction was considered more of a Caucasian genre. Specifically, male Caucasian. Most of the pioneers of the genre were men of the dominant culture. Occasionally, a woman might slip in, and on occasion, somebody of colour might be found hiding behind a couch, but for the most part, the field was essentially—if you’ll pardon the pun—whitewashed.

So as a struggling, up-and-coming young Ojibway writer, the idea of writing Native science fiction was completely a foreign concept. You see, Native people simply did not write science fiction. Just like we did not write erotica, murder mysteries, vampire novels or fantasy books. No more than a fish could ride a bicycle or trees could tap dance. (Ironically, also in the recent past, Native people weren’t allowed to leave their reserve, hire a lawyer or hold a powwow. So, with all those more pressing problems, we really didn’t notice what we were not allowed to write about.)

I never felt this was right. Within the Native community, our imagination, our sense of what is possible was as wide, as expressive and as detailed as any other people on the face of the Earth. Why couldn’t we write science fiction? Many of our traditional stories could easily be classified as such. Different Indigenous nations have numerous stories about star people coming to Earth, or women falling from the sky, or people travelling up into the stars. Images on pictographs and petroglyphs have been theorized by some to represent possible alien travellers. It was all there; you just had to be aware of what you were looking for.

Luckily, in recent years, the perception of what Native authors are capable of writing has broadened. In your local bookstore are collections of topics as varied as Indigenous erotica (sort of a 50 Shades of Red), a fantasy trilogy with elves, magic and swords written by a Native writer, and even murder mysteries penned by the famous Thomas King. It was only a matter of time.

This new openness to Indigenous sci-fi is also reflected in visual art and film. Earlier this year, the Toronto International Film Festival asked six Indigenous artists—including Kent Monkman and Scott Benesiinaabandan—to use VR to envision Canada’s future 150 years from now. Montreal artist Skawennati, who represented Canada at the 2015 Biennial of the Americas, is known for her work TimeTraveller, which uses science fiction to examine First Nations histories. Calgary-born filmmaker Benjamin Ross Hayden showed his futurist feature The Northlander, set in 2961, at Cannes earlier this year.

But even with this shift in pop-culture awareness, I still felt obstacles to writing sci-fi myself.

Here’s why: the origins of my new sci-fi book have a dark and foreboding origin. For a long time, I have had a reluctance to immerse myself in the world of prose. Yes, through sheer willpower and a need to pay the mortgage, I have managed in the past to pump out two novels and a previous collection of short stories. But prose is not a field I find myself eager to plow.

I have long been more comfortable weaving tales onstage, through live dialogue or personal storytelling. The world of prose is a harsh and difficult taskmaster, one requiring a comfortable knowledge of such creatures as split infinitives and dangling participles. Having been educated in my early years on the reserve, many of these concepts have felt beyond my expertise.

As a result, my first idea for tackling a sci-fi book was to compile and edit a collection of other Native writers’ sci-fi stories. I contacted the cream of the Aboriginal crop of Canadian writers, inquiring if they might be interested in exploring and contributing a science-fiction anthology. Practically to a man (and woman) they all enthusiastically agreed, eager to see to what planets and universes their keyboards took them to.

But alas, this dream was not to be. The field was too new and unexplored, and possibly a little too expensive considering the talent I had wanted to engage in my fantasy. Several publishers failed to bite at the prospect, and the project fell dead. I was very disappointed.

Then I had one of those epiphanies writers get occasionally. I was sitting at home in a deep funk, and I think I literally said, “Ah screw it, I’ll do it myself.”

Nothing generates a book like frustration. I had been so excited and so pumped for this project for so long, I wrote six stories in four months and then four stories in the next six months, and before long, I had a book. It was one of the easiest projects I had ever worked on, and one of the most enjoyable. I almost want to thank those publishers for turning down my original concept.

Technically speaking, I think one of the metaphors most likely to catch on in the Native sci-fi writing community—if and when one develops—will be the exploration of contact. With aliens or multi-dimensional creatures or parallel universes or whatever. I say this because, as the adage goes, write what you know. And we know very much about contact. In fact, for the most part, we are still dealing with it.

Originally from the Curve Lake First Nations in Central Ontario, Drew Hayden Taylor is an award-winning playwright, author, columnist, filmmaker and lecturer. His latest book, released in October, is the sci-fi short story collection Take Us to Your Chief and Other Stories.

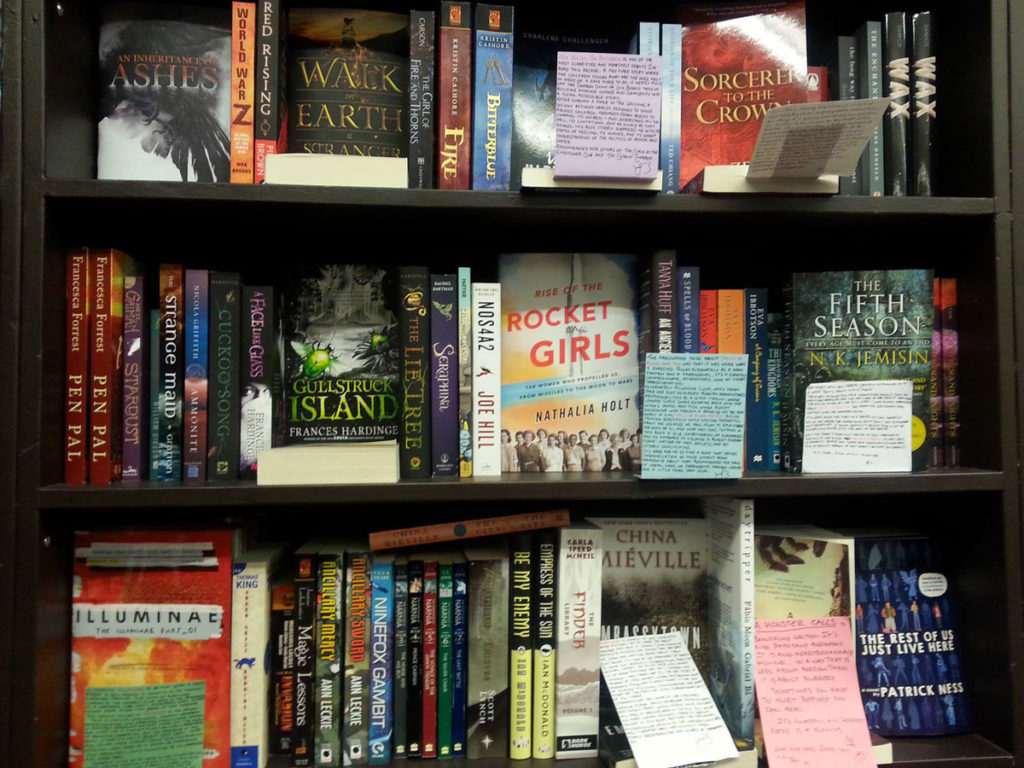

The shelves at Bakka Phoenix Books in Toronto are full of sci-fi—a growing part of it Indigenous, like Drew Hayden Taylor's new book Take Us to Your Chief and Other Stories, which launched there in October. Photo: Bakka Phoenix via Facebook.

The shelves at Bakka Phoenix Books in Toronto are full of sci-fi—a growing part of it Indigenous, like Drew Hayden Taylor's new book Take Us to Your Chief and Other Stories, which launched there in October. Photo: Bakka Phoenix via Facebook.