A right-wing US presidential hopeful threatens the remaining comfort left to the privileged few, as widespread environmental devastation and economic collapse destabilize imperialist countries like Canada and the US. Families huddle in walled neighbourhoods, keeping organized shift-watch during nights. They work outside the home only one day a week to avoid danger.

This is the uncanny vision of late US speculative-fiction writer Octavia E. Butler, as told in her incomplete trilogy Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). Butler’s story begins here, but it is by no means where it ends.

In Parable of the Sower, when neighbourhood walls finally fall, people form a community and, together, try to figure out how to survive. There is a shared and ever-shifting understanding of the nature of change, social justice, disability justice and the experience of marginalization and difference. The leaders of a new, emergent “nation” are disabled and BIPOC (black, Indigenous and people of colour), forming an intergenerational collective. Naturally, they come with very different ideas for moving forward, which both aids and challenges their continued survival. They are motivated by the strong words of Butler’s main character, Lauren Oya Olamina: “All that you touch / you Change. All that you Change / Changes you.”

Butler herself experienced a compromised sense of belonging. She was a disabled, black artist, and a woman writing science fiction—a field that remains largely dominated by men and, as Butler often spoke about, can be outwardly hostile toward women and trans-identified writers. Butler’s compromised citizenship inspired her to create worlds in which those of us on the margins could imagine ourselves surviving. She created worlds in which we might storytell ourselves into thriving existence.

Butler seemed to be on the minds of many on November 8, 2016, as many watched in horror as conservative forces swept through the US electorate, taking the presidency and maintaining control of the House and Senate, with at least one Supreme Court appointment to follow. President-elect Donald Trump’s slogan, borrowed from Ronald Reagan’s 1980 campaign, mirrored that of ultra-conservative presidential hopeful Christopher Charles Morpeth Donner in Parable of the Sower: “Make America Great Again.” There are other similarities. Donner dismantles the “‘wasteful, pointless, unnecessary’ moon and Mars programs,” and abolishes “‘overly restrictive’ minimum-wage, environmental, and worker protection laws.” He gives increasing power to big business, permitting gross labour-rights violations as long as workers are provided “training and adequate room and board.”

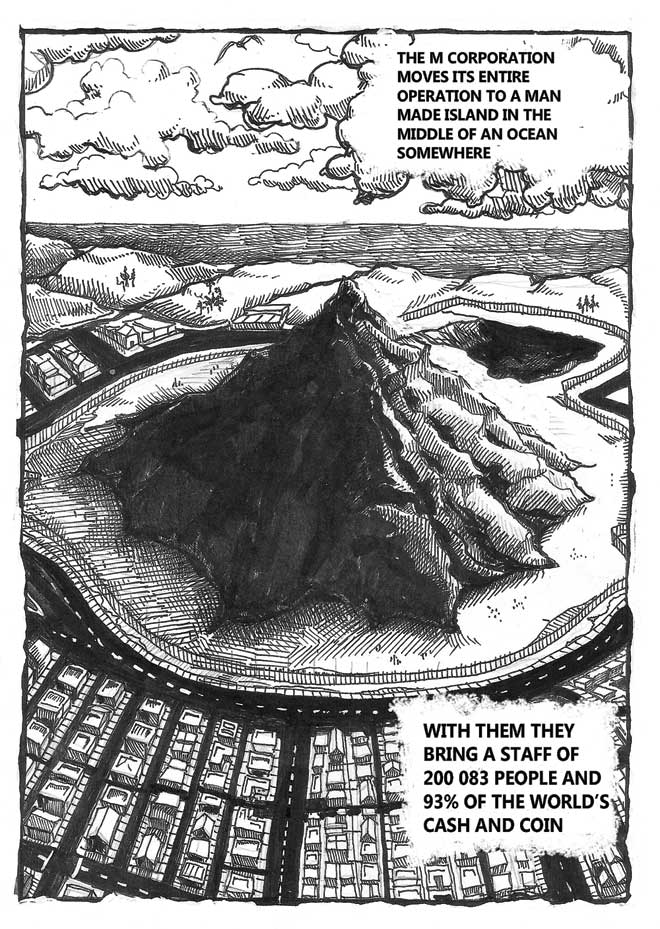

A panel featuring the M Corporation from Janine Carrington’s Human Beings are Rats, 2015.

A panel featuring the M Corporation from Janine Carrington’s Human Beings are Rats, 2015.

There seems a real risk of a Donner reality, in which, for one, democracy is thoroughly corporatized. In Parable of the Sower, Donner’s presidency ushers in company towns such as Olivar, with enslaved people “working off” their debts to the company. In these towns, workers are only allowed to buy things with company money and are barely paid enough to survive, ensuring they remain trapped in the town. These towns remind me of the fictional “M Corporation” in Canadian artist Janine Carrington’s graphic novels, Human Beings are Rats, wherein this mythical corporation has taken over the world’s economy, completely controlling finances by securing all remaining government-produced monies in giant piles on M Island, which is guarded by the stories’ protagonists.

Such horrors have been imagined by those fighting for justice as well as by the Donners and Trumps of the world, who have the resources and power to make them a reality. What Butler does so well is to offer something to hold onto. In Parable of the Sower, Lauren writes Jenny Holzer–style truisms in her journal that later become the texts of her spiritual community: Earthseed: The Books of the Living. These truisms give us a window into Lauren’s life as she tries to unite a strong, BIPOC and disabled–led community rooted in self-determination in a world that is constantly changing. They are also words that I will be holding onto throughout 2017:

When apparent stability disintegrates,

As it must-

God is Change-

People tend to give in

To fear and depression,

To need and greed.

When no influence is strong enough

To unify people

They divide.

They struggle,

One against one,

Group against group,

For survival, position, power.

They remember old hates and generate new ones,

The create chaos and nurture it.

They kill and kill and kill,

Until they are exhausted and destroyed,

Until they are conquered by outside forces,

Or until one of them becomes

A leader

Most will follow,

Or a tyrant

Most fear.

Butler toured her last book, Fledgling, to Toronto in 2005. I had the chance to spend the day with her and talk about the Parable series, about Earthseed and about her time-travelling book, Kindred. I was fascinated by her remarkable ability to predict the reality that we are now living in. I had always found Butler to be a sort of truth-seer, her writing to be prophetic, and I wanted to understand how she was able to do this magic. It was as if she was capable of living the now, but decades earlier.

She brushed off this suggestion, stating simply that she was writing a future based on the present. She explained that in the late 1980s, she considered that if humans followed the trajectory that we are currently on—environmental carelessness, growing class divides, white supremacy upheld at the highest levels of government and basic human nature—what would happen? Butler wrote the Parable series during the height of the Gulf War, of challenges to environmentalism, of violence and police brutality—the Rodney King beating, a growing Prison Industrial Complex and a country still plagued by the expansive legacy of slave labour. One of the texts in Earthseed states,

All struggles

Are essentially

power struggles.

Who will rule,

Who will lead,

Who will define,

refine,

confine,

design,

Who will dominate.

All struggles

Are essentially power struggles,

And most are no more intellectual

than two rams

knocking their heads together.

I asked Butler what she thought of people taking up Earthseed as a living spiritual practice. There were few, if any, fully formed Earthseed communities at that time, but the seeds were being planted (excuse the metaphor). I wanted to know what she thought of us taking up her texts for guidance, of following them in literal ways. She was surprised and perhaps even dismissive, saying she couldn’t imagine Earthseed as a comforting “religion.” She felt strongly that the idea of a faceless god that was simply “change itself” would not be useful for followers during times of stress. She explained that most successful religions offered comfort during moments of personal and global chaos. She questioned how we would find comfort in the idea of change as the only constant—in an understanding that struggle was a core part of being alive.

Toshi Reagon, Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower: the Concert Version Performance at the Public Theater, New York, January 2015. 120 minutes. Courtesy MRA Agency. Photo: Kevin Yatarola.

Toshi Reagon, Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower: the Concert Version Performance at the Public Theater, New York, January 2015. 120 minutes. Courtesy MRA Agency. Photo: Kevin Yatarola.

Since Butler’s passing, however, more and more have turned to Earthseed as a way to find a sense of purpose and safety. These people are building intentional communities modelled after Acorn, the first such community in Parable of the Sower. These real-life communities are rooted in concepts of shared work, respect and love of children, social-justice frameworks, disability and healing justice, and a way of living in harmony with nature. They root their work in kindness, drawing again on Earthseed: The Books of the Living, in which Butler states, “Kindness eases Change.” They meet regularly with each other, sharing ideas, creativity and love and also drawing on suggestions in the text that,

Once or twice

each week

A Gathering of Earthseed

is a good and necessary thing.

It vents emotion, then

quiets the mind.

It focuses attention,

strengthens purpose, and

unifies people.

Artists are also taking up Butler’s texts as creative fodder. Musician Toshi Reagon created an opera based on Parable of the Sower, and Butler’s books have spawned an anthology of new writing, Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice, featuring speculative fiction and essays by LeVar Burton, Mumia-Abu Jamal and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, among others. It seems Earthseed is continuing to grow and change. As Butler states, “We are Earthseed / The life that perceives itself / Changing.”

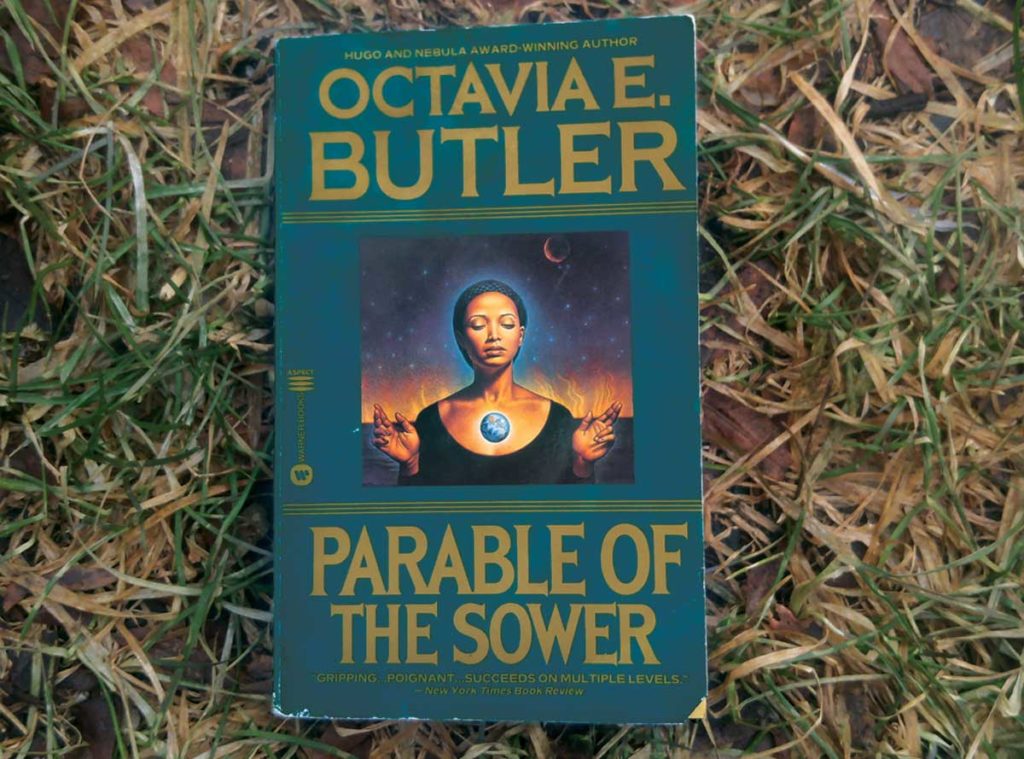

Cover art by John Jude Palencar for Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower , published by Warner Books in 1995.

Cover art by John Jude Palencar for Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower , published by Warner Books in 1995.