The exact dates are of some debate, but here are a few truths known with approximate certainty. Artemisia Gentileschi was 17 in 1610, the year she painted her version of Susanna and the Elders, an exceptional painting for its technical skill and an emotional departure from classic artistic depictions of the apocryphal story. A beautiful Hebrew wife is caught bathing by two old men who attempt to blackmail her: unless she fucks them, they’ll say she fucked someone else. Susanna refuses—no to them, no to their threats—and is tried in a court set to kill her when she is saved by Daniel, who traps the elders with a clever question about what tree Susanna was sitting under when she met her supposed lover. The men contradict each other, revealing their lie, and they are killed. Susanna remains untouched.

The moment when the elders first approach Susanna was a favoured subject for many painters of that period. The art historian Mary D. Garrard has noted that Gentileschi’s version was unlike male artists’, who had depicted a “sexually exploitative and morally meaningless interpretation,” because they too were men, and they left their sympathies with the elders rather than Susanna. Gentileschi’s Susanna is shown contorted by her distress, trying to get away from these men and their violent manipulations. Gentileschi sees no sexual allusion in this dynamic, unlike her male contemporaries, who considered the story to be about seduction and only peripherally about the attempted possession of a woman who has refused. Their preferred visual language did not distinguish between a woman who says yes and a woman who says no.

Gentileschi was 19 in 1612, when she gave her testimony against Agostino Tassi, her father’s colleague, a painter hired by the family to teach the young artist about perspective. He raped her after she said no, and then promised to marry her; in court, her oath was tested under torture. When her fingers were put into the thumbscrews she is said to have yelled at Tassi, “This is the ring you give me, and these are your promises!”

“No” is a clean word. Simple and direct, saying it is supposed to refuse harm, or give protection. “No” has a dirty meaning—when people with less power use it, people with more power can choose to selectively hear it. People identified as women, in particular, are often told to just say no; they are also told, in actions and in art, that their no meant nothing. More so than the unwanted advances it is supposed to discourage or the violence it is supposed to prevent, the word “no” is so taboo that it is denied meaning at the moments it matters most. If we are trained to believe that saying no is enough, then finding out it was never your word to say is another promise broken. Artists who work with ideas about the function of sex as power—whether in gender identity or sexual expression or both—must find a way to express the negative, the contrary, the refusals and rejections in their work, so that their definitions of sex, sexuality, power and gender are both heard and understood.

Emma Sulkowicz was finishing Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight) (2014–15)—the much-discussed performance piece in which they protested Columbia University’s response to their sexual assault on campus by carrying a standard-issue dorm mattress everywhere they went—when they began to plan another piece, Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol, a video with accompanying text that lives on a website with the same domain name. In it, Sulkowicz and an unknown male actor are seen in a dorm room from the perspective of four security cameras, acting out a choreographed encounter; to those familiar with Sulkowicz’s story, what happens between them will look like a re-enactment of the sexual assault cited as the impetus for Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight). But it is not a re-enactment of rape, as Sulkowicz explained when I spoke to them on the phone in mid-January of this year. It is a work of art about what happens when a person says no and is not heard, and it is one in which Sulkowicz retained complete control at all times. “In the performance, I’m saying no and I’m expressing no via body language, but there’s so much that went into the making of that piece, such as consent forms that my actor and I signed, so that the whole performance would be consensual.… Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol is not necessarily a reclamation of the word ‘no,’ but an enactment of my own form of ‘yes.’” As an artist, and as a person, Sulkowicz says they consider the way they use the word “no” in their practice. “It’s scary to say no, because most people don’t think they have a right to, and even when they do it doesn’t work,” they explained. “I’m trying to find ways to make ‘no’ work for me.”

While editing the film, Sulkowicz was reading Rae Langton’s essay “Speech Acts and Unspeakable Acts” (1993), a philosophical analysis of the limits of the word “no” in the context of pornography and sexual violence, in which the author describes a secondary form of silencing. The powerful could stop the powerless from speaking entirely, but, Langton argues, there is also another way to silence them: “Let them speak. Let them say whatever they like to whomever they like, but stop that speech

from counting as an action. More precisely, stop it from counting as the action it was intended to be.”

In the January 2018 issue of Artforum, critic Johanna Fateman compared Sulkowicz’s work to that of Ana Mendieta, whose 1973 performance Untitled (Rape Scene) took an image and separated it from a “lascivious visual economy of journalism, pornography, and art history.” The resulting photograph, Mendieta bent over a table with blood drying as it runs down her legs, suggests violence as being only the beginning of an ignored “no”—what happens when a “no” doesn’t count enough to be considered an action or direction. Fateman, too, sees something of a Gentileschi painting in the “baroque gloom” of Mendieta’s staging.

The New Museum in New York recently presented “Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon,” curated by Johanna Burton, and as Fateman writes in her survey of art that examines power and sexual violence—and the conflation of the two—the show “takes as a given that we live in a world shaped by sexual violence.” I visited the exhibition before it closed in January 2018, and walking through it felt like listening to a high-octave note playing quietly in the background; there was an urgency to the ideas and emotions on display, as well as a calm, certain trust, both in the artists’ works and in their reception by the audience. Artists such as Tschabalala Self, Sable Elyse Smith and Harry Dodge, and collaborators like Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, Reina Gossett and Sasha Wortzel, House of Ladosha and many more, all had works presented that spoke to the art and artists that came before them, and communicated what they needed to say at this moment, trusting that we, the viewers, would listen. Mickalene Thomas’s 2016 video installation Me As Muse layers art history and cultural conventions underneath the artist’s own image: over 12 stacked television sets, flickering images of Thomas’s body lying like a traditional odalisque fade in and out, cut with images of Grace Jones and Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, while an audio recording of Eartha Kitt plays, the actress telling stories about violent incidents in her life and in her family history, andhow the word “no” was denied to her and the women who raised her. The quilted effect of Thomas’s chosen mixed materials—images, video, voice, overlapping to create a complete whole—says much about the ways Black women are silenced when they are made into muses without their conditions respected or their permission given.

I was, I think, wondering how to rate her work as being evidence of a “yes” when so much of it was predicated on hearing “no.” There’s a sudden escalation felt when an artist identifies a taboo and makes that taboo the work itself

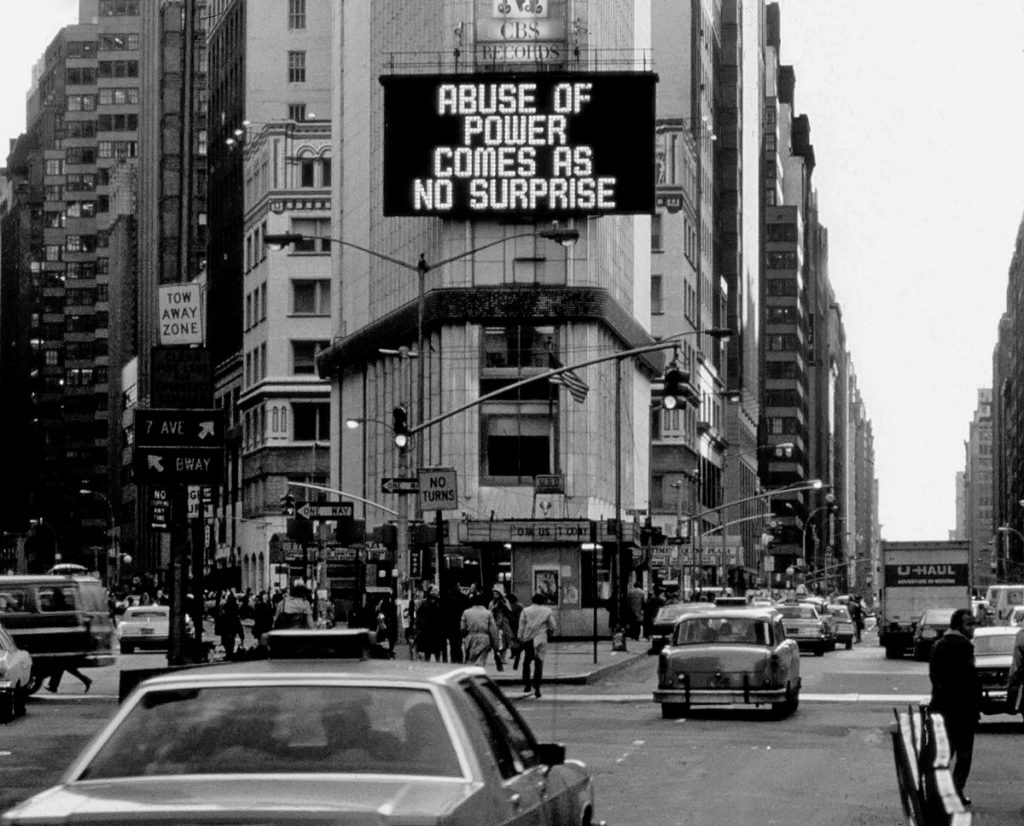

Last year, the conditions of the art industry itself were the subject of an organized and anonymous “no.” Referencing one of Jenny Holzer’s famous Truisms, “Abuse of power comes as no surprise,” the collective called themselves Not Surprised, as both a title and a feeling. Identifying themselves only by their numerous job titles—all “workers of the art world”—they pledged to stop keeping secrets for those who, to no one’s surprise, abuse their power. “We will denounce those who would continue to exploit, silence, and dismiss us.… Where we see the abuse of power, we resolve to speak out, to demand that institutions and individuals address our concerns seriously, and to bring these incidents to light regardless of the perpetrator’s gender.” The letter was released in October 2017 after Knight Landesman, a publisher at Artforum, resigned following multiple reports that he had sexually harassed or intimidated women early in their careers. The collective received over 9,500 signatures before they had to stop, citing an overwhelming influx of names and the demand it placed on their team of volunteers. The word “no” gave the impetus for the letter, as they explained that they had been denied their right to say no before and were not going to wait for someone to give them the right to say no now. The collective’s intentions can be found on their website: an FAQs page addresses criticisms of exclusivity, or of replicating the same hierarchical problems the industry already has, and a bullet-point list identifies their next steps, which include holding open meetings for industry-wide concerns, establishing confidential networks of communication and writing a communal code of conduct. It was, like many first steps, mostly symbolic—a show of solidarity in the form of signatures—which suits art as an industry, a field designed to give a vocabulary to symbols and attach meaning to actions. Their “no” went back and forth in time, retroactively making the word a record of responses they hadn’t been able to give in the past, and anticipating what they would have to refuse, again and again, in the future.

For some artists, saying yes to what had previously been denied feels like the most freeing thing. Carolee Schneemann’s retrospective, “Kinetic Paintings,” on until March 2018 at MoMA PS1, was filled with works that show her commitment to saying yes: yes to controlling her own representation, yes to saying what she felt she needed to say in the way she wanted to say it. Schneemann started as a painter in the mid-1950s, and her Bard College professors suggested that she sit as a nude model for other painters. Instead, she painted herself nude, and was ultimately asked to leave the school because, in their estimation, making herself both an artist and a subject in this way was evidence of “moral turpitude.” This kind of double bind intentionally acts as a double negative: it deletes the artist’s intentions, and erases their possibilities. Schneemann’s work has always been held as a symbol of necessarily confrontational and biologically literal feminist art, such as Interior Scroll from 1975, which is part of her series of works that makes the vulva into a mouth that speaks, meant to question how the anatomy of a woman is used by others as a substitute for her voice.

Decades removed from when Schneemann first presented the pieces collected at PS1, I found myself unsure about how to understand them. I respect all of her work but could feel myself gravitating away from the images of genitals and toward her works in which words and actions are used together. Fuses, her 1965 experimental silent film that shows her having sex with her then-partner, as seen from the perspective of her cat, is beautiful: sexual, of course, but it mostly communicates how romantic and intimate she found their sex to be, and it is so funny to see scenes of their fucking intercut with shots of her indifferent cat blinking. The slideshow ABC—We Print Anything—In The Cards (1977) includes 156 numbered, colour-coded index cards, plus photos, all documenting the dreams and conversations that tell a story of protracted heartbreak between herself and two men, which all read like truisms of their own.

I was, I think, wondering how to rate her work as being evidence of a “yes” when so much of it was predicated on hearing “no.” There’s a sudden escalation felt when an artist identifies a taboo and makes that taboo the work itself; with Schneemann, the “no” becomes the conditional centre of the idea, and the “yes,” rather than being its own response, is only the inverse of what someone else has said. In their own way, all of these artists have been denied “no,” and have moved on from the question of whether or not it was their word to say. Instead, they have asked: what does the word “no” do? Gentileschi took a story she had heard, and gave it a meaning based on what she knew, as a woman whose work and life were guided and controlled by men. Sulkowicz and Mendieta, in their performances, have shown the passive cruelty of the voyeur’s perspective, and given a symbolic language to the material realities of sexual violence. Thomas’s video keeps history underneath the work itself, flickering like the static on her television sets, to show how it influences and shapes her self-conception. These works all similarly function like a complete story—characters and an arc, an open-ended conclusion that is still enough of an ending to satisfy—rather than the single words expected to do so much.

Jenny Holzer, Truisms (1977–79), 1982. Electronic sign, 6.1 x 12.2 m. Installation for “Messages to the Public,” Times Square, New York, 1982. Copyright Jenny Holzer/SODRAC (2018). Photo: Copyright Lisa Kahane.

Jenny Holzer, Truisms (1977–79), 1982. Electronic sign, 6.1 x 12.2 m. Installation for “Messages to the Public,” Times Square, New York, 1982. Copyright Jenny Holzer/SODRAC (2018). Photo: Copyright Lisa Kahane.