The year was an exciting one for Indigenous art in so-called Canada—likely somewhat propelled by the Canada Council’s newly created funding stream for Indigenous art. I can’t think of another period—outside of 1992, the 350th anniversary of the birth of Montreal and 500 years since Columbus did not discover America—when Indigenous art was this dynamic. This year was host to a diverse group of new voices for Indigenous art, an array of artists and curators who established themselves as strong leaders and key figures in this new wave of contemporary Indigenous art. Joi T. Arcand, Dayna Danger, Asinnajaq, Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter, Becca Taylor, Tsēma Igharas, Jeneen Frei Njootli and Lacie Buring come to mind, to name only a few. Is what Tanya Harnett told me true—are we witnessing the emergence of a seventh wave in Indigenous art within so-called Canada? Whatever this moment is, it’s adamantly feminist; run by women, gender variant and sexually diverse peoples; and entrenched in values of care and reciprocity.

Selecting only a couple events for this year-end review was difficult. Of course, my selection is based on what I was personally able to see, which feels so limiting considering all the Indigenous art happenings that transpired this year. I could mention many other highlights such as Tiffany Collinge’s installation at the National Gathering of Elders, or Ociciwan’s showing of Dayna Danger’s Big’Uns series at Latitude 53, more respectably and reciprocally installed than I’ve witnessed to date. Community favourite Ursula Johnson won the Sobey Art Award, and there wasn’t a dry eye in Indigenous art across Turtle Island. Ursula’s win also signalled something bigger—a shift in Indigenous art, perhaps, and the ushering in of a new generation of diverse and loving voices. The street art convergence in Montreal that proves women are leading this generation’s Indigenous muralism movement. Witnessing queer and trans Indigenous artists displayed so prominently and with such reverence at the Vancouver Queer Arts Festival was another personal highlight—in particular, the careful work Adrian Stimson put into curating an art show for QAF that was intergenerational, representative of vast territories and communities, and activated by a community of queer Indigenous artists. Even from a distance, Stimson’s show felt like the intent and action of an established artist carving out spaces for new generations of queer artists.

The Feminist Art Project took over the College Art Association conference to hold a day of panels on Indigenous feminism in New York, which built new networks and discourse between Indigenous feminist art practitioners—but also brought up a lot of questions about the relationship between the American and Canadian art scenes. Namely, why do Canadians take up so much space in the American discourse about Indigenous art? When chatting with American arts editors at the 2017 Native American Art Studies Association Conference, I realized that the pervasiveness of Canadian art discourse in America results from invisibilization of Indigenous communities in the United States. While Indigenous artists in America have expressed concern about their local communities’ ignorance regarding the art within their own colonial borders, it was a revelation to hear that Indigenous peoples’ artistic resistance in Canada has been so potent that it’s now influencing international art scenes. The internationalization of Canada’s Indigenous art discourse was further confirmed when it was announced that UNCEDED would represent Canada at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, and that Inuit art collective Isuma would represent Canada at the 2019 Venice Art Biennale.

Truly, 2017 was a year of—and for—Indigenous art in so-called Canada, and one that influenced art communities far beyond our colonial borders in ways that we won’t know the full impact of for years to come. To all the Indigenous artists, curators and administrators who contributed to our vibrant communities this year, kinanâskomitin, kinanâskomitin, kinanâskomitin, kinanâskomitin—one time for each direction.

An installation view from “Carry Forward” at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. Photo: Robert McNair.

An installation view from “Carry Forward” at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. Photo: Robert McNair.

Carry Forward at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery

Walking through “Carry Forward” was an exercise in slowing down time. The exhibition is installed to take up a great deal of space throughout the gallery. As such, I had to slowly make my way through various rooms to fully engage with all the works, and there was also a necessity to sit with many of the works presented, to take them in over a period. Curator and artist Lisa Myers chose the analogy of “carrying forward” to describe the act of bringing something to the next generation, an action which she explores throughout her curation. In particular, Myers focuses in here on engagements with “authority and authenticity of documents and documentation” through artworks that “reveal the biases and racism of dominant ideologies enshrined in official papers.” But there’s also an element of positive mentorship throughout between the artists in the show—and interestingly in how Myers and the artists become mentors to the audience, teaching them problematic histories.

I could hear fiddle music playing out of the first darkened room I was drawn to, and my Red River roots navigated me in its direction, where I was greeted with Marjorie Beaucage’s video Speaking to Their Mother (1992). Beaucage recorded the video during the summer of 1992 when Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore brought Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother to the Mother Earth Wiggans Bay Blockade in Northern Saskatchewan. Belmore installed her now-famous megaphone, which she invited community members to speak to the land through, all documented by Beaucage on tape. In “Carry Forward” Myers publicly displays the translated words of community members who were documented at the site speaking in to their mother, many of whom were elders. These translations on display were provided by Beaucage; they underline the gravity of any decision to translate Indigenous languages, and for which audiences. I won’t share these words outside of the gallery space, honouring Myers and Beaucage’s care in dealing with the translations. But I will say the words were all beautiful offerings and prayers to our Mother, and all the love she holds.

Another element that struck me about Beaucage’s video was the implication of watching it in its entirety now, 25 years later. The video contains significant portions of an interview with Belmore, a quarter-decade younger and perhaps a little less jaded by the arts and culture industry. In a way, here, Belmore is speaking to herself through the generations, reminding of the radical possibility for Indigenous and community-based art. I attended the show with an artist friend of mine who was riveted watching Belmore describe all the things that Indigenous art can achieve—love, revolution, connectedness to the land, and so much more. So Belmore was not only speaking to herself through generations, but to the next generation as well.

It’s true that art history is made by the living. Indigenous art, in particular, is influenced by living figures who continue to drive discourse. As such, there has been little significant historicization of Mike MacDonald’s seminal video and media artworks, and his important contributions to the Indigenous media art canon. I was elated to see MacDonald’s famous work Seven Sisters (1989) in “Carry Forward.” As with with many of MacDonald’s artworks, the viewer is forced to reconnect with the timing of nature. In the hustle and bustle of daily life, sometimes we lose the rhythm and pace of the natural world. In fact, one of my favourite things about Indigenous artists is how they often halt the never-ceasing drone of production and colonial-capitalist structures naturalized within art by disrupting temporality and slowing down time: through NDN time! Seven Sisters somehow it manages to be as breathtaking as the British Columbia mountain range that is its subject and namesake. MacDonald compiles various visualities, including film taken from above, possibly in a helicopter, taping the expanse of each mountain that is a part of the Seven Sisters mountain range, as the wild west coast wind stirs the snow on their tips. The TVs presenting the videos are each of differing sizes, emulating the differing scales of each of the mountains. As Myers notes, MacDonald reminds us the land itself is a document of destruction and deforestation; this reinforces the importance of archiving colonial brutalization of Indigenous lands, and the necessity of presenting images of environmental degradation to juxtapose with more idyllic images of the mountain range.

At the risk of sounding cliché, sitting with Deanna Bowen’s installation for “Carry Forward” changed me. Deanna Bowen has monumentally installed a copy of the 1911 petition opposing the migration of Black peoples to Edmonton—a document that comprises 234 pages. The expanse of the petition is shocking, taking up an entire gallery wall. I lived in Edmonton for several years before moving east, and I associate trauma with the city due to pervasive racism against Indigenous people, particularly at the hands of the Edmonton Police. Yet somehow I had erased the Black community and their presence within Edmonton, as well as the spatialities of anti-Black racism they experience simply existing in the prairies. After seeing Bowen’s installation, I realized that perhaps this was intended and taught to me through dominant white settler-led discourse. I’m reminded of Robyn Maynard’s book Policing Black Lives, which made waves in Canadian publishing this year; Maynard considers how erasure functions to uphold a chronology of unbroken state violence on Black bodies, a chronology that manifests in a contemporary affect of anti-Black racism amongst white settlers.

While preparing the petition for the exhibition, KWAG’s registrar recognized a name among its many signatories and, by comparing the signature on the petition to archival correspondence, confirmed that Barker Fairley, an artist represented in KWAG’s permanent collection and friend of the Group of Seven, had signed the petition. KWAG was also able to confirm that Fairley was in Edmonton in 1910, a recent immigrant to Canada who had moved from the UK to teach at the University of Alberta. While this is a horrifying discovery, it forces those who participate in the Canadian art industry to reckon with the cultures of anti-Black racism entrenched within the arts. Further, like many higher education institutions within Canada, it would seem that the U of A was built on a culture anti-Black racism.

I found myself frantically taking photos of all the names present in the petition with a sense of urgency I couldn’t quite explain, as if I wanted to pass on the names to every person I could, and expose the histories of anti-Black racism that define Canadian identity. To see the last names of some of my colleagues and friends on the petition shocked me: Sullivan, Fraser, Pitt, Roy, Sleeman, Wilson, Robertson, Bellamy, Williams, Lawrence, Russell and hundreds more. But a name that bore an eerie resemblance to that of my white relations (Dixon) shook me to my core. These are the legacies that all white settler Canadians must contend with.

John G. Hampton’s artwork Histories of Cape Spear (2016/17) focuses on online documentation and the ways it can become encoded with values of colonial domination— specifically by archiving a series of interventions on the Cape Spear Wikipedia page. In recent years, this Wikipedia page has been repeatedly edited that so it describes a moment in 2011 when artist Duane Linklater visited Cape Spear and watched (as well as videotaped) the sunrise. (Linklater did the Wikipedia interventions himself until roughly 2015, then he passed stewardship of the piece on to Hampton.) I found myself caught up in laughter at the series of interventions made on the Wikipedia page, and the hilarity that has ensued as settler administrators and editors have continuously erased what they classify as “vandalism,” citing the need for a “reputable” source. There is an element of absurdity to the work as Wikipedia admnistrators scramble to remove these additions to the Cape Spear page. Here, Hampton, building on the work of the project’s initiator, Linklater, exposes the racist and colonial cultures that pervade online documentation, though it’s often assumed to be a space for intellectual freedom. He also perhaps makes a little fun of stringent and uptight settler actors who so anxiously cling to said structures along the way. Seeing the work reconnected me with love for my brothers, specifically my blood kin, those wily coyote tricksters who disrupt through good humor, bringing humility to colonial institutions.

I haven’t had such an emotional response to an exhibition since seeing works from Amy Malbeuf and Kent Monkman early on in my Indigenous art nerd days. Dare I say that “Carry Forward” was my favorite exhibition this year?

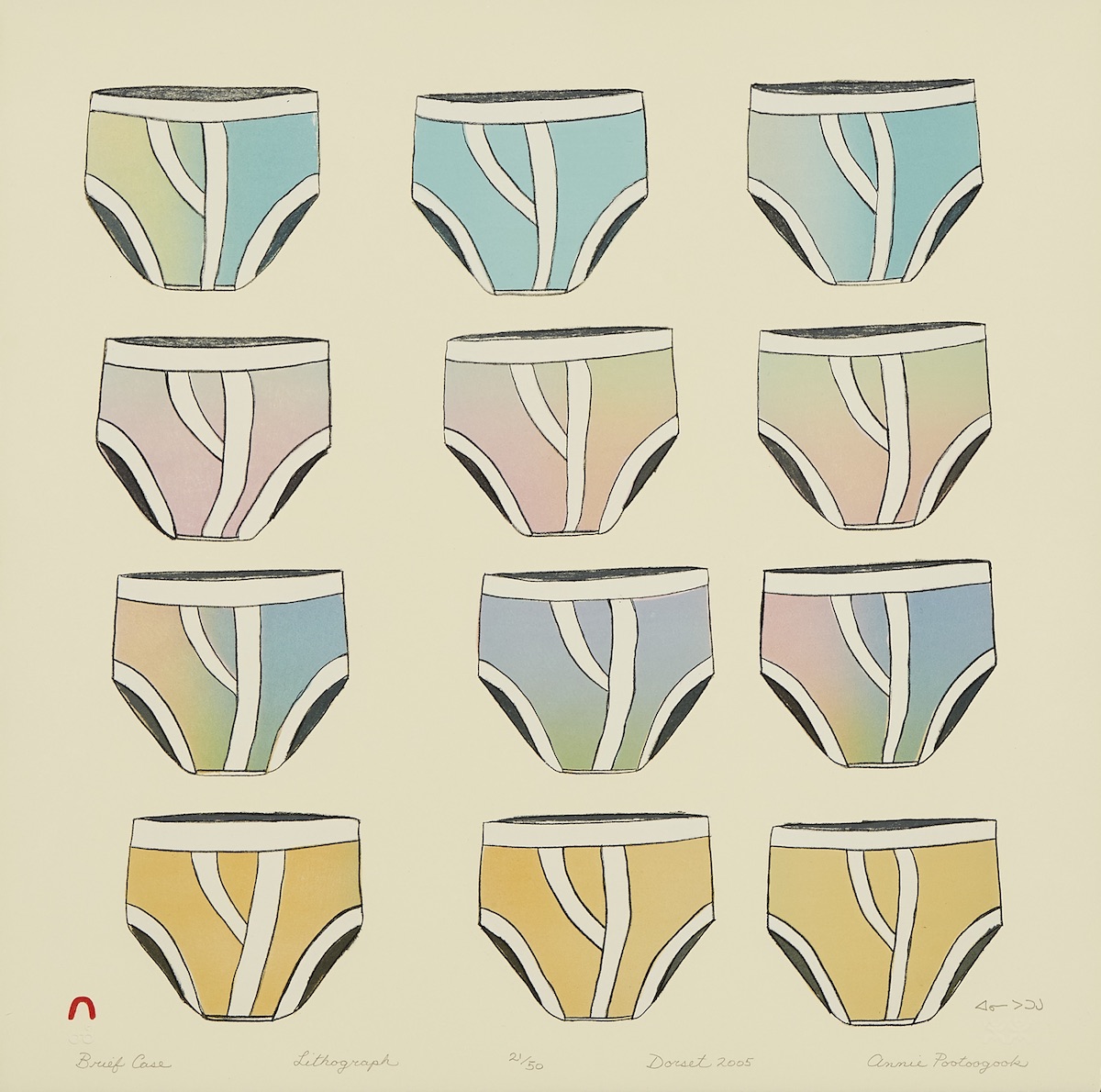

Annie Pootoogook, Brief Case, 2005. Lithograph on paper, 43.5 x 43 cm. Collection of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Reproduced with the permission of the artist’s estate.

Annie Pootoogook, Brief Case, 2005. Lithograph on paper, 43.5 x 43 cm. Collection of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Reproduced with the permission of the artist’s estate.

raise a flag at Onsite Gallery at OCAD University

Collecting is a facet of art institutions—a facet desperately in need of intervention—that we often lose sight of within Indigenous art activism. As Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter pointed out in her recent article for Canadian Art, galleries still predominantly collect and show anthropological works when considering Inuit artwork, which affects Canada’s art criticism about Inuit peoples, in essence halting generative and progressive representations of Inuit within Canadian art discourse. Ossie Michelin also wrote a compelling investigative article for Canadian Art‘s summer issue, collecting interviews with artists who were shocked to see the dismal collection of Indigenous art in institutions across Canada, as well as the differentiation in prices between Indigenous and settler art. How can we ensure more ethical relationships between the art industry and Indigenous artists if we aren’t talking about the critical work of reforming Canada’s collections? And, more generally, how can we ensure those ethics if we aren’t even talking about the importance of collecting Indigenous artists?

With “raise a flag,” curator Ryan Rice, chair of Indigenous Visual Culture at the OCAD University, sought to shine a light on an often ignored collection: the Indigenous art collection at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Rice felt it was particularly important to activate this collection—essentially lifeless Indigenous bodies held within a Canadian institution—during a year when conversations around reconciliation were at the forefront. (And why was that? Because of celebrations surrounding recognition of Canada’s 150 years of Indigenous genocide.) As a Cree-Métis-Saulteaux person, I often feel like I have to “warrior-up” when talking about Haudenosaunee curation. In true form, Rice positions the works in “raise a flag” as “taunts” meant to provoke colonial institutions and their administration of Indigenous life—a visual contestation of nationalism and Canadian identity, reforming the idea of nationhood on Turtle Island through Indigenous worldviews. Rice is reframing a collective Indigenous history within the borders of so-called Canada, a history that includes Indigenous understandings of time, space and place.

Annie Pootoogook’s lithograph Brief Case (2005) stood out to me, especially given that she left this world too soon in 2016. As Heather Igloliorte has taught me, the accessibility of printmaking made a significant impact on the quick dissemination of Inuit political philosophies and resistance within the Canadian art scene, facilitating the rapid sharing of images, ideas and visualities to buyers far from the North. Brief Case is satirical, poking fun at the English language and its nouns made for claiming and naming—a facet of colonial capitalism and extractive projects that reinforce imperialist dominion over vast territories. Many Indigenous languages are verb-based, describing relationalities to forces, beings and objects within all creation, the opposite of Western languages entrenched in colonial logics. Through the use of humor, Pootoogook confronts the descriptive words that settlers use to claim everyday objects through Western ideologies—in this case, the word “briefcase”—by depicting rows and rows of differently coloured underwear, to absurd effect. The viewer, perhaps a settler, can be made uncomfortable with the reality that, while they have been told they hold a superior language, it’s actually quite illogical and creates a comical effect to some outsiders, with its nonsensical naming and claiming.

Seeing Dana Claxton’s c-prints Tatanka Wanbli Chekpa Wicincala (2006) at this juncture of her career was a reflective experience. After all, 2017 saw the emergence of new forms of visual sovereignty—like Dayna Danger’s bold representations of Indigenous women, gender-variant and sexually diverse populations. Dana Claxton, along with other photographers like KC Adams, is an auntie to this generation of bold Indigenous feminist photography, redefining the space behind and in front of the lens. Tatanka Wanbli Chekpa Wicincala confronts Western commodification of Indigeneity, as well as Western photography’s exploitative representation of inanimate Indian maidens à la Edward Curtis. Instead, these women are alive and rowdy, with cheeky smiles spread across their faces, caught mid-headbang. Claxton playfully considers what is real and manufactured about Indigenous identity and the femme bodies that resist commodification by living, breathing, fighting and loving in the contemporary.

Seeing Claxton’s work now, and considering it in relation to the current Indigenous feminist movement in photography, proves to me that despite what critics say, Jolene Rickard’s seminal 1995 essay on visual sovereignty, “Sovereignty: A Line in the Sand,” still holds true all these years later. A masculinist and antagonizing critique had emerged in recent years, purporting that Rickard moves to define Indigenous art through colonial legal concepts. Such critiques have always felt reactionary to me, and not at all rigorous considering Rickard was attempting to describe Haudenosaunee lifeways with limited colonial language, and the intricacies of colonial language and legalese are being used to perpetuate carceral relations around Rickard’s theory. In conversation of late with a dear friend and personal idol of mine, Kai Cheng Thom, we discussed how microcosm communities like Indigenous art (in our case, we were discussing queer “community,” whatever that means) are often grounded in scarcity-based rhetorics that feed on our elders in an attempt to consume their power and elevate emerging individualistic egos. All this to say, don’t get it twisted: Jolene Rickard has always been, and always will be, one of our most influential Indigenous art historians.

Viewing Rebecca Belmore’s Fringe (2007) for the first time was particularly emotive, just as Leanne Simpson describes it in her vital 2013 book Islands of Decolonial Love. In her poem “small pox, anyone?” Simpson describes the feeling of seeing Fringe at a crowded gallery in Montreal. Insensitive settlers mull about the space, talking about frivolous issues in their everyday lives. But Simpson is totally transfixed, despite it all, at the visually devastating image that Belmore has confronted her with: an Indigenous woman with a deep cut across her back that has been sewn shut. Across the wound are rows of red beads, in the place of blood, hanging from the stitched cut, healing the body they adorn. For Simpson, Fringe is a reminder of the ways colonialism cuts through her own body and attempts to make a bloody home there. Simpson concludes her poem by saying:

i’m wondering:

when i cut my back like that

can you sew me up

the same way with

the fringe and the beads?

Simpson feels the trauma presented by Belmore embodied in her physicality. She is not just viewing the work: she is experiencing it and reflecting upon the ways settlement—and her interactions with settlers—cut into her body and tear open her flesh, just as Belmore portrays. Fringe is not only a song of trauma, but of gratitude for healing through art, culture and decolonial love.

All the works present in “raise a flag” are, indeed, potent taunts at the Canadian settler regime, including several more works and artists than I can describe in this short section. Luckily, Rice’s equally compelling educational guide is still available to read on OCADU’s website.

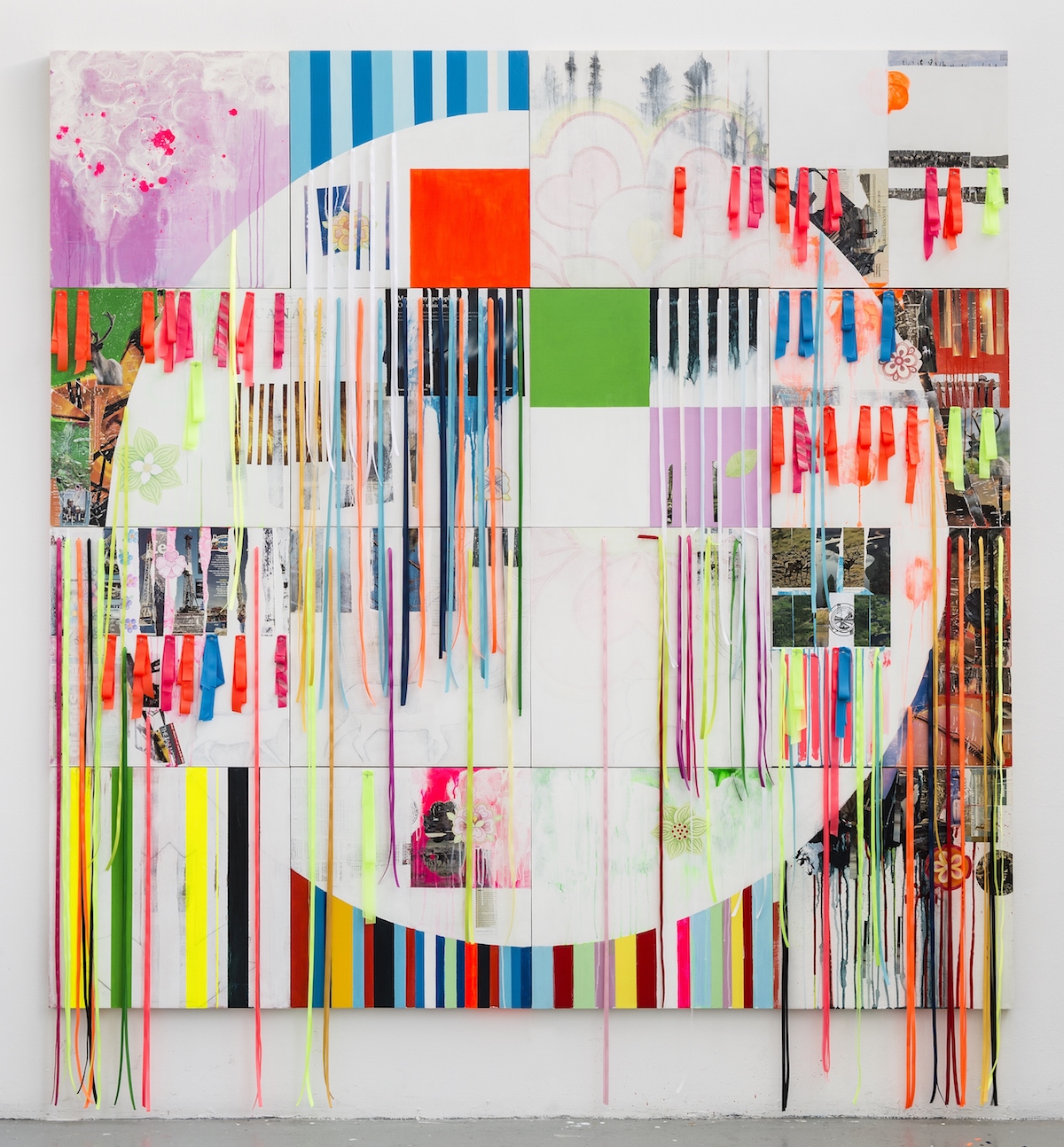

Bruno Canadien, Hustle & Bustle/Downriver House, 2016. Acrylic, graphite, coloured pencil, found images, flagging tape and satin ribbon on panel, 274.3 x 243.8 cm. Collection of the artist.

Bruno Canadien, Hustle & Bustle/Downriver House, 2016. Acrylic, graphite, coloured pencil, found images, flagging tape and satin ribbon on panel, 274.3 x 243.8 cm. Collection of the artist.

Insurgence/Resurgence at the Winnipeg Art Gallery

Winnipeg Art Gallery curatorial dream team Julie Nagam and Jaimie Isaac certainly do not shy away from taking up space where necessary, and “Insurgence/Resurgence” is an exercise in taking up space. The scale of “Insurgence/Resurgence” is huge, spanning hundreds of feet throughout the gallery, a presence I felt as soon as I walked up to the WAG. I was greeted by Jordan Bennett and Dee Barsy’s striking paintings prominently displayed at the front doors, letting everyone who passes know that they are on Indigenous territories. The paintings were immediately recognizable to me, as they had quickly become an unofficial iconic image for the exhibition, rapidly spreading across NDN Instagram: sovereignty one selfie at a time.

As soon as I entered the main lobby, Hannah Claus’s grandiose and breathtaking installation of the sky world was the first thing that drew my eye: Cloudscape (2012). Each cloud was meticulously installed strand by strand, a prayer to the upper cosmos. For an accompanying symposium titled The Future Imaginary (presented by the Initiative for Indigenous Futures and supported by Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace, Video Pool and other institutions) a performance night was programmed wherein throat singers, hoop dancers, fiddle players and other artists staged a concert under Claus’s billowing material clouds. I was moved to tears when I witnessed Indigenous children mirroring the dancers, learning the footwork and moves. Intergenerational affect permeates throughout the show. There is even a section of the gallery allocated for children to draw and participate in activities that can bring them into a more profound understanding of the content throughout, in ways they can comprehend.

One of Kent Monkman’s large-scale paintings of Winnipeg’s famously Indigenous-run neighborhoods also resides in the foyer, using cubist imagery to disrupt representations of “othered” bodies in Western art. During the night of performances mentioned above, my friend’s brother who is an Indigenous youth from Selkirk (a small community just outside of Winnipeg) was engrossed with the work, which made me reconsider the current discourse in Indigenous art around Monkman’s paintings. Indigenous thinkers and creators have increasingly begun to cite Monkman’s work as not community-based and as pandering to colonial mediums, collectors and gallerists. As professionals in Indigenous art, we get caught up in our individualized careers—yet another facet of scarcity-driven ideologies within the Indigenous art industry—sometimes so much so that we ironically lose sight of community when we do critique one another. Monkman’s work can still be transformative and compelling to an Indigenous youth, one who lacks the institutional and economic privilege that many of us who comprise the Indigenous art industry retain. In Monkman’s paintings, my friend’s brother saw himself and his community represented in art for the first time— something I remember being a life-saving experience myself as an Indigenous youth witnessing Miss Chief Eagle Testickle for the first time.

The rest of the symposium was equally eventful, its days packed full of panels with amazing thinkers, creators and curators from all over the world. The exchanges created when that many Indigenous art figures get together often progresses the discourse greatly, as we don’t often get to share those knowledges while isolated in our settler-dominated organizations and fields. It was so plentiful and productive, there is no way I could summarize all that was happening there in the short article. But I implore you to check out all the panels on the abtec.org website.

A critique that emerged amongst my generation of peers at the symposium was that, for a symposium about the Indigenous future, it was interesting to see so much of Indigenous art’s future largely in the audience—a literal queer femme army. The symposium felt more like Indigenous art of the past decade considering its future, rather than youth gratefully picking up the discourse of past generations and progressing it forward, as they should (very much a part of my Cree, Métis and Saulteaux teachings). There were many notable exceptions, like Niki Little’s panel, Carla Taunton’s panel on IndigiFem and the future, and the very compelling Kauwila Mahi, a former Skins participant, on Julie Nagam’s panel. Also, there was Heather Igloliorte’s artworld-changing announcement that she would curate the forthcoming opening exhibition of the WAG’s Inuit Art Centre with three emerging Inuit curators: Jade Nasogaluk Carpenter, Krista Zawadski and Asinnajaq. (Take note: this is how you do Indigenous futures right.)

A colleague also mentioned to me that it was interesting to see no focus on LGBTQ+ issues at the symposium, even after Billy-Ray Belcourt’s eloquent 2016 essay “Can the Other of Native Studies Speak?” I found myself agreeing. And so I implore my colleagues to take their responsibilities to sexually diverse and gender diverse community members seriously, because emerging thinkers have shown that class, gender and colourism will paramount issues for the next generation, which is becoming disillusioned by a flattening of difference within Indigenous thought (including thought about art).

“Insurgence/Resurgence,” however, was chock-full of voices from the next generation of Indigenous art. As I moved further into space, I came upon one of Joi T. Arcand’s now-viral syllabic interventions installed into the staircase leading up to the second floor of the WAG: Don’t Speak English (2017). Arcand, a renowned syllabics nerd, restructures spatialities with her mediations that immediately alienate settlers with their presence. Much like Bennett and Barsy’s paintings, Arcand’s works have created an Instagram sensation this year, likely because she seems to understand the visualities of the fem Indigenous future quite genuinely. Unfriendly NDN hotties are enacting social media sovereignty, taking back digital space one “don’t-fuck-with-me” stare at a time with their rapid sharing of Arcand’s work through Indigenous feminist selfies (perhaps even alongside an Aunty Magic earring or two).

Asinnajaq’s work Tunnit (2017), dealing with Inuit facial tattooing—which Asinnajaq herself received this year—was presented alongside artworks by her relations, kin who influenced her art practice: Simeonie Weetaluktuk’s sculpture Woman with Jig and Fish (1980) and a basket woven by Lucy Anullaq Weetaluktuk. While relational aesthetics seems to be making a comeback, with Tunnit, Asinnajaq reminds that Indigenous art has always been relational, influenced by our communities and mentors, and enacted in spaces of community care. Asinnajaq facilitates an immersive space for viewers to take in her video and zine about face tattooing, just like the space of love and intimacy created when she received her tattoos. Asinnajaq even worked seal pelts into the shapes of hearts, which the viewer is meant to sit on while they watch her video installation and thumb through her accompanying zine. A page of the zine entitled LESSONS reminds:

what hurts for a moment

passes;

we are beautiful.

On the topic of “INTEGRITY,” Asinnajaq argues that,

putting belief into action

gives life a clear path.

After a particularly difficult year in the Indigenous art industry, I was moved to tears while taking in Asinnajaq’s work.

Tunnit isn’t the only appearance of Indigenous tattooing practices in “Insurgence/Resurgence.” Earthline Tattoo Collective, which is committed to reclaiming Indigenous tattooing practices as well as mentoring other Indigenous peoples in tattooing practices, received a license and gave tattoos at the opening for “Insurgence/Resurgence.” Its makeshift “tattoo studios,” decorated with personal objects of intimate importance to the artists, will remain in the space for the rest of the time the show is up. Designs that emulate Indigenous tattoo aesthetics were also used on the cover of the catalog for “Insurgence/Resurgence.” The last several years have seen a vast reclamation of Indigenous tattooing practices, and a recognition of their essential spiritual, political and cultural power within Indigenous art.

Again, I wish I could go into greater depth about the amazing artworks I experienced at “Insurgence/Resurgence.” For instance, Tsēma Igharas is quickly becoming one of my favorite artists, and Esghanãnã (Reclamation) Series (2016) did not disappoint. Here, Igharas continues her material exploration into the visualities, spirit, language and power of urban Indigenous resistance. It is much like her previous rebel rock series, but this time manifested through stencils, spray-paint and sound. I can’t wait to see where Igharas takes her potsent vision next. Amanda Strong’s work Biidaaban (2017) screens at the show, and her carefully constructed mini sets are on display. Strong is quickly situating herself as having a potent voice and a meticulous practice, and as an artist to watch. Nagam and Isaac’s newly published catalog is fabulous and well worth the purchase, for in-depth considerations of all the works present at “Insurgence/Resurgence.” I’m anticipating what is to come from dream team Isaac and Nagam, and I feel so incredibly lucky to have witnessed the fantastic achievement of “Insurgence/Resurgence.”

Lindsay Nixon is Indigenous editor-at-large of Canadian Art.

Clarifications and corrections were made to this article on December 29, 2017; January 3, 2018, and February 20, 2018. The original review implied that John G. Hampton originated the Cape Spear Wikipedia page interventions in his artwork in “Carry Forward.” Duane Linklater originated the interventions and carried them out for a number of years before passing stewardship of the project on to Hampton. The original review indicated that Lisa Myers translated the words in Marjorie Beaucage’s video in “Carry Forward” for display; the translations on display were Beaucage’s. An event originally referred to as an Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace symposium was actually presented by the Initiative for Indigenous Futures; according to its website, the IIF is a partnership of universities and other organizations conducted by AbTeC. And the paintings at the front doors of the WAG are by both Jordan Bennett and Dee Barsy; previously, only Bennett was credited.

Mike MacDonald, Seven Sisters, 1989. Video installation, running time: 7 videos, 55 minutes each. Courtesy of Vtape, Toronto © Mike MacDonald. Installed at “Carry Forward” at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. Image courtesy of KWAG. Photo: Robert McNair.

Mike MacDonald, Seven Sisters, 1989. Video installation, running time: 7 videos, 55 minutes each. Courtesy of Vtape, Toronto © Mike MacDonald. Installed at “Carry Forward” at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. Image courtesy of KWAG. Photo: Robert McNair.