In print publishing, you’re always living in the future. At present, the issue of Canadian Art out on newsstands, our Winter 2017 issue, is titled “Futures,” but we wrapped production on that issue over a month ago, and are in fact already in the middle of production on our Spring 2017 issue, which takes the theme of “Structures.”

So when I look back at the cultural experiences that have been meaningful to me in the recent past, with my mind having been trained during that time on seeking issue-related topics, what I’m really talking about is looking into the future—but not the kind of future contained in our “Futures” issue, because actually, that already belongs to the past. Do you follow?

“Structures,” like all of our themes, is deliberately broad and open-ended, and is meant to be interpreted in many different ways. Without giving too much away, we’re looking at the interior and exterior physical structures of institutions as well as the power structures that prop them up; at how canons and archives structure biased readings of history; at how our bodies are structures in themselves, shaping the spaces we occupy through movement and scent; at artists actively disrupting and deconstructing existing structures; and much more.

In my own life, I experienced much disruption this year, though most of it was self-imposed, and intended to guide personal growth. After more than a decade of back-to-back long-term relationships, I spent most of 2016 single. Along with navigating the shift in identity that inhabiting this status precludes, becoming single also meant living and, for the first time, travelling alone. Eating and sleeping alone. Confronting my problems and taking enjoyment in my pleasures alone.

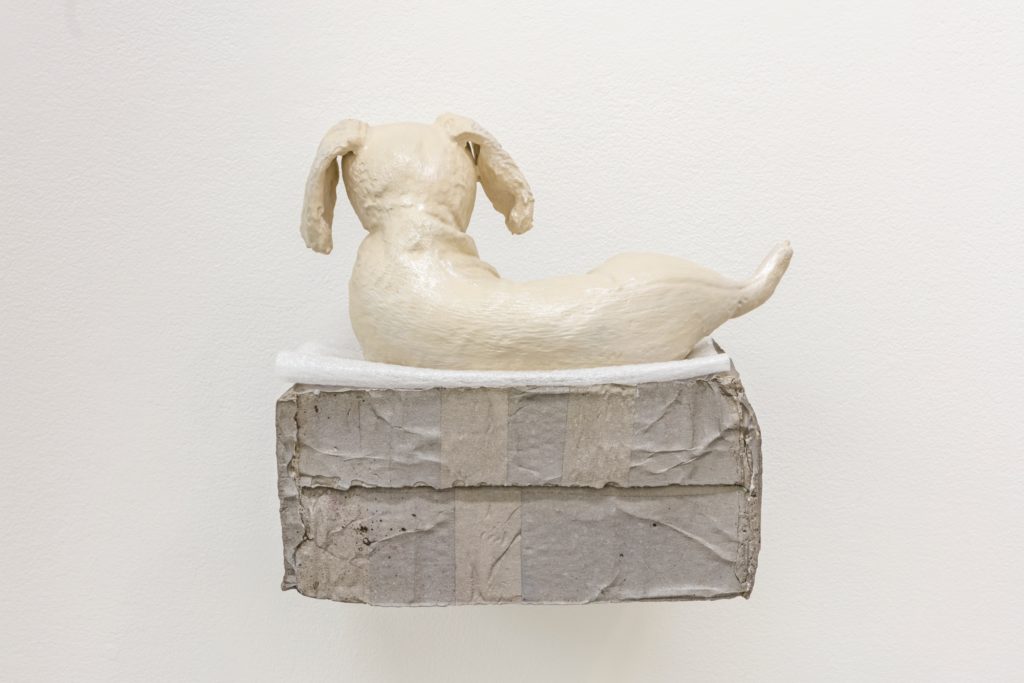

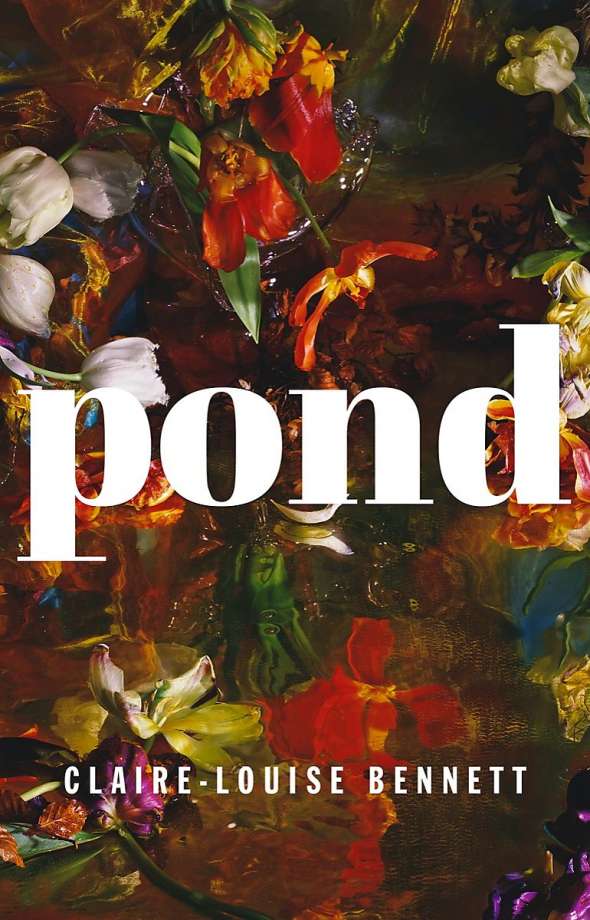

Claire-Louise Bennett, Pond (Riverhead Books, 2016)

Claire-Louise Bennett, Pond (Riverhead Books, 2016)

The books I read this year that I loved the most—Vivian Gornick’s The Odd Woman in the City, Joni Murphy’s Double Teenage, Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, Emily Witt’s Future Sex and Claire Louise Bennett’s Pond—all traffic in the interior lives of unattached women. I chose to read them all purposefully, using them as beacons to steer me as I lived through my very own coming-of-age story.

I wrote about Double Teenage and Future Sex already, in our Fall 2016 and Winter 2017 issues respectively, and I’ll limit myself to exultations of just Pond for this review, because more than any of my other reads this year, it met the criteria ascribed to books I know I’ll love forever: by the time I’d thumbed through it, its bottom half was thicker than its top, by virtue of how many page corners I’d folded (underlining passages in books is blasphemous, no matter how pretty your pen is); I became so engrossed in it that I frequently missed streetcar stops and was late for social/professional appointments; I read it slower than I wanted to, because I couldn’t bear for it to end; and as soon as I finished it, I started back again at the beginning.

I came to the novel fresh, after it was recommended to me by a friend with impeccable taste, and I want it to recommend it the same way she recommended it to me: without giving anything away or telling you my favourite lines, because you’ll love it, just trust me. She also handed me an orange to peel while she said that, so imagine that I’m doing that, too.

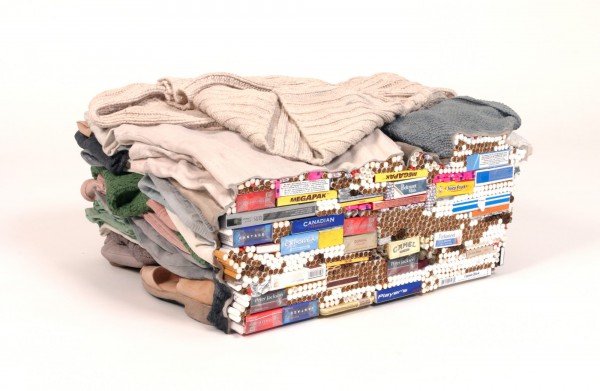

Liz Magor, Pearl Pet, 2015. Courtesy the Shlesinger-Walbohm Family Collection, Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Liz Magor, Pearl Pet, 2015. Courtesy the Shlesinger-Walbohm Family Collection, Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

I visited that friend while I was in Montreal, one of the many cities I travelled to alone this year, with the aforementioned books as my companions (I also went to Philadelphia, Mexico City, Reykjavik, London, Ottawa, Montreal again, Los Angeles, Banff and Miami—almost a new city each month). On that Montreal trip, I saw my favourite show of the year, Liz Magor’s “Habitude” at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Looking through my photos from that visit, I realize took as many photos of the wall labels as I did the artworks. The label for The Most She Weighed/The Least She Weighed (1982) read, “During the early 1980s, Magor made a series of sculptures and book works that referred to a conversation the artist had with a woman who related changes in her weight to significant events in her personal development…weight was very much intertwined with Dorothy’s conception of her true self.” Part of navigating the world alone, for better or worse, means not having to make concessions to the eating and sleeping habits of others. I’m the type to forget to eat unless someone reminds me, and in the photos of myself from this year where I look my “best” (by which I mean the least I weighed), I was likely also at my loneliest.

Installation view of “No Visible Horizon” at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff.

Installation view of “No Visible Horizon” at the Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff.

I travelled alone to Banff in October, where a solitary work provided the basis for the Walter Phillips Gallery’s 40th-anniversary exhibition, “No Visible Horizon.” In the exhibition catalogue’s introductory essay, curator Peta Rake talks about how horizons have been traditionally viewed as stable constants upon which western understandings of navigation, orientation, perspective and reliability rest, whereas really, “the horizon is provisional, the very ground around us is changing.” In Walter J. Phillips’s 1923 woodblock print Flying Island, there is no horizon line—just a lone, unmoored landmass floating in rippling water. A group of artists and writers, all of whom had been connected to the gallery in some capacity in its 40-year history, were invited to respond to this one small work for the exhibition.

Rake describes the Phillips work as depicting “A possible place, its ecosystem only slightly revealed.” During my visit, I felt that this could have been an apt description for the Banff Centre itself. It operates somewhat like a mythological floating island, or maybe more like Buckminster Fuller’s Cloud Nine tensegrity spheres, designed to house floating, self-contained communities who could breathe cleaner air. I certainly felt the city sludge in my lungs dislodging after my first gulp of pristine Banff air, and there is something otherworldly about the place. At any given time, a shifting community of invited artists stay for fixed-term residencies in houses shaped like seashells and boats in the forest. I saw wild deer grazing in the late Mike MacDonald’s Butterfly Garden, heard stories about ghosts haunting Farrelly Hall, and, as fluffy snowflakes gently fell down during my hike up Tunnel Mountain, I indulged in the fantasy that I’d entered an idyllic commune that exists in a time and space slightly apart from reality and its horrors.

And indeed, this year has brought a bounty of horrors. More than 60 million people, 20 million of whom are from Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia, have been displaced, their homes obliterated. Communities such as the Standing Rock Sioux had to defend their rightful land against being ravaged by the rabid jaws of corporate greed. There were mass shootings, outbreaks of disease, civil rights threatened, force majeures. Brexit happened two weeks after I visited London, and Trump was elected two weeks before I visited Miami. In 19 BC, Roman poet Horace said, “It’s your business when your neighbour’s wall is in flames.” In 2016, it was our neighbour’s dumpster.

Those of us privileged enough to live in areas of immediate safety watched the horrors unfold from a distance, through news headlines and Twitter feeds. We spent our evenings tucked safely in bed, watching television programs and films, such as Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror and Adam Curtis’s HyperNormalisation, that did nothing to alleviate our anxieties. We watched the kids in Netflix’s ’80s-pastiche Stranger Things enter the Upside Down, an inverted and flipped-inside-out version of their own homes that had been infiltrated by a terrifying monster.

Brittany Shepherd, from “of Flight and of Leak” at Roberta Pelan, Toronto.

Brittany Shepherd, from “of Flight and of Leak” at Roberta Pelan, Toronto.

Collectively, we mourned the passing of artists who died this year, among them Annie Pootoogook, David Bowie, Prince and Leonard Cohen, who famously sang, “There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.” In one of the most recent exhibitions I went to, Brittany Shepherd’s “of Flight and of Leak” at Roberta Pelan in Toronto, attention was placed on the cracks, traces and leaks that connect people and places, sometimes without their noticing. Strands of hair stuck to polyurethane bars of soap sat unassumingly on ledges in the gallery bathroom, a soundtrack installed into the gallery walls played muted noises that seemed to come from other lives being lived out—renovations, a couple fighting, a funky club—and pools of resin poured over photographs of carpets and floorboards created portals to other rooms, one of which contained the tail of a darting pet bearded dragon.

I’m ending my year in a very happy place, in a new relationship. A few weeks ago, I adopted a scruffy one-year-old mutt whose routine I’m now bound to, whose life depends on mine. I’m looking at time now as full-bodied, waggy-tailed, beating-heart animal, whose form gives my life the structure I need.