This month, a week after my second trip to Vancouver this year, journalist Masha Gessen was quoted in the Atlantic describing waiting as “a defining condition of powerlessness in the modern world.” Gessen proposed this in the context of her Hitchens Prize–winning coverage of migrants and refugees, a context that must be asserted, since it is clear that many who are imposing this contemporary condition (I would correct Gessen’s use of “modern”) could stand to wait a lot more than they are—could stand, in other words, to share the waiting.

In a city like Vancouver, as a variety of investors wait to make even more money, those subject to the whims and violence of such investment wait, too. On the western edge of the continent, waiting could now be an apocalyptic pastime. When is the next extreme weather event? When will we be renovicted? How much water has gone over the sea wall now? Waiting could be a state of staving-off, of short-sight, of in-comparison-to: When will the ruptured pipeline be repaired and the natural-gas shortage end? Waiting could be delusional. When will things go back to normal?

During that second trip I stayed in Vancouver’s West End, north of Denman Street and south of Stanley Park, a neighbourhood full of midcentury-modern high rises, often claimed as the most densely populated urban area in Canada. A development-application sign—its Google Map–coloured green and blue now normalized to Vancouverites—stood in front of my hotel, proposing a taller, uglier building with “19 market strata units.” Google itself was not far. Its Street View cars were going up and down laneways, which now have name signs, which now are “real” streets, which now are fair game for development. Traffic counters on every block, large black cords running from curb to curb, collect data, trying ominously (preventatively?) to detect some future-facing change.

Farther west, at the Museum of Anthropology, multi-coloured chalk-marks on the Arthur Erickson–designed building’s large concrete stanchions signal the need for seismic upgrades. MOA is making these upgrades into an exhibition: “Shake Up: Preserving What We Value,” running to autumn 2019, and, according to MOA’s website, attempting to “bring to light the convergence of earthquake science and technology with the rich Indigenous knowledge and oral history of the living cultures represented in MOA’s Northwest Coast collection.” Visitors won’t be able to see the Great Hall, as it is known, with its famed, theatrical, amassed totem poles, but they will be able to see the poles lowered, undergoing restoration at the same time as the upgrades.

Who will build the new Vancouver Art Gallery? What will that matter to what is programmed within it?

After the MOA, I visited a noted collector-donor-philanthropist and asked for an update on the Vancouver Art Gallery’s proposed new building, the Herzog and de Meuron renderings for which were released in spring of 2014—another time, it feels like. The collector-donor-philanthropist wasn’t able to confirm anything. (“I could tell you, but I’d have to kill you,” they joked.) Subsequent to this I heard rumours that the renderings are controversial to potential donors in part because they deploy so much wood, which weathers when exposed to the city’s elements. Some, the rumours say, are demanding the wood elements be encased in glass. In Vancouver, glass is fast. I recalled my March trip to the city, when I stayed in a glass coach house in a backyard in Strathcona, currently the city’s hottest real-estate market, and worried about being surveilled by my AirBnB host, while contemplating Julia Feyrer’s exhibition at Catriona Jeffries, “Background Actors,” about, among other things, proprioception, ASMR and ways of sensing and seeing the body differently that occupy, and arguably mutate, time.

At the Vancouver Art Gallery’s existing building, a former court house, Hunkpapa-Lakota (Sioux) artist Dana Claxton’s show “Fringing the Cube” runs to February 3. As Claxton asserts an Indigenous presence in an institution, she does not ignore one’s awareness of viewing the work from within the institution, mixing work from the VAG’s permanent collection with a wide swath of her own. At present, regardless of who is curated into institutional shows, or indeed who is employed to facilitate them, there remains the matter of diversifying audiences. (Downstairs from Claxton’s show, fashion designer Guo Pei attracts sizeable crowds from Vancouver’s Chinese diaspora, in what feels like an overt effort on the VAG’s part.) “Art collections speak and reveal themselves, as curatorial listening involves an openness to hear the soul of the artwork,” Claxton writes in a didactic text.

Labour is one of four thematics Claxton uses to divide her engagement with the VAG’s collection (the others being “Face/Head,” “Red” and “Analogue Photography.”) In the labour section, Claxton’s photographic series NDN Ironworkers provides a basis for a broad and provocative meditation on a variety of work forms and their representations. In the institutional gallery, labour remains, by default, either represented in images and/or theory, or invisible. In NDN Ironworkers’s centrepiece, a light box (Claxton calls it a “firebox”) depicts eight Indigenous construction workers, playful and defiant, within the vernacular of Vancouver photoconceptualism. If they, as many figures in large-format photoconceptual light boxes do, stand between the real and the archetypal, their subjectivity on the verge of dissolving, they also seem to ask a question specific to the space in which the viewer stands: Who will build the new Vancouver Art Gallery? What will that matter to what is programmed within it?

In July of this year, as we entered production on our Fall “Climates” issue, I began to have nightmares about climate change. It is a luxury to only be having these nightmares now. (“Do you want to know about the future?” asked Elizabeth A. Povinelli in a talk she gave at the Banff Centre last year. “Ask the people already living in it.”) In November, in Vancouver, as I went back and forth from my hotel to Denman in the rain, buying cigarettes and wine, and/or going to the gym, after long days of talking to many different people who told me many different things about the city, I listened mainly to Goldfrapp, a UK band popular in the ’00s that I randomly resurrected on Spotify. I felt old, and gay. I loved, in particular, “Koko,” a decadent glam-dance song, named after a London club, and with the catchy refrain, “Soon be nothing of this world, soon be nothing.” I recalled the simplicity with which I first enjoyed the lyrics, recognized the glib truth they now spoke, and prepared to witness, if I waited just a little bit longer, a shift from fantasy to reality.

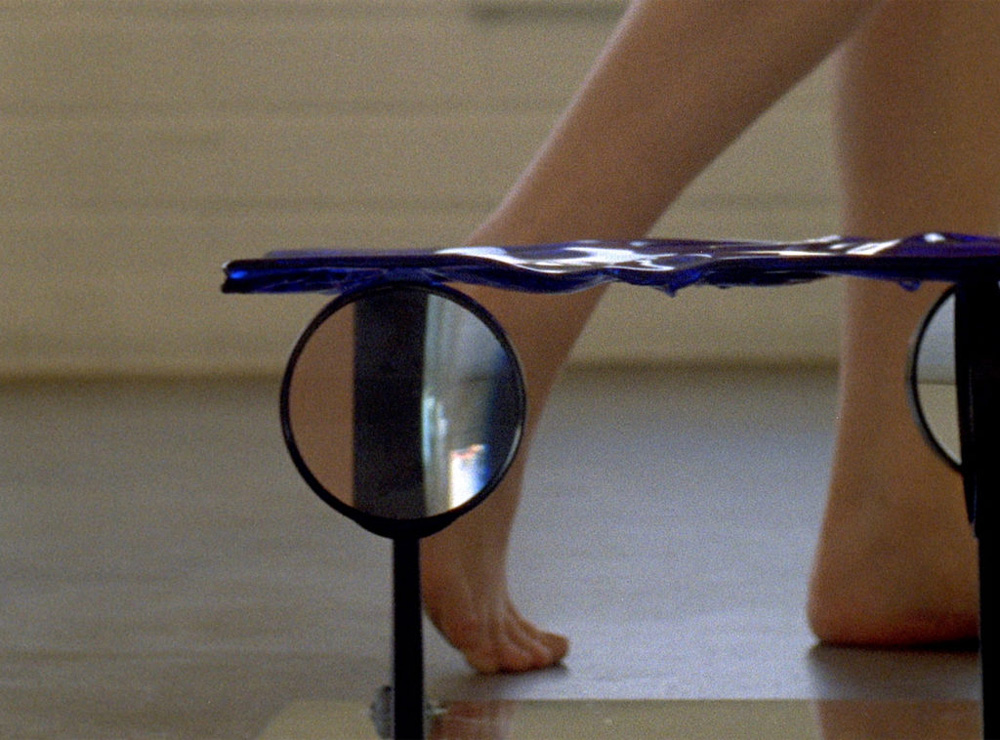

Julia Feyrer, New Pedestrians (still), 2018. 16mm film transferred to digital with sound, 4 minutes. Photo: SITE Photography. Courtesy of Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver.

Julia Feyrer, New Pedestrians (still), 2018. 16mm film transferred to digital with sound, 4 minutes. Photo: SITE Photography. Courtesy of Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver.