On a 1964 recording of Leonard Bernstein’s Symphony No. 3 (“Kaddish”), a deep, slightly frayed female voice beseeches:

O, my Father: ancient, hallowed,

Lonely, disappointed Father:

Rejected Ruler of the Universe:

Handsome, jealous Lord and Lover:

Angry, wrinkled Old Majesty:

I want to pray. I want to say Kaddish.

My own Kaddish.

…there may just be

No one to say it after me.

The words melt like an incantation—“magnified and sanctified be the great name”—as the orchestra’s screech rises in dissonant augmented fourths; in her call to majesty I see the woman’s face. She compares herself to the Rose of Sharon, a lily of the valley, angry and in prayer. The speaker’s voice is that of Leonard Bernstein’s wife, the actor, painter and activist Felicia Montealegre. She was my grandfather’s cousin. I am fascinated by her odd fame, adjacent as she is to her husband’s legacy. There is nothing written explicitly about her or her artworks, but she can be found along the margins of what has been written about Bernstein’s life, politics and compositional philosophies. There are small fragments of her in the Bernstein archives. In fact, her output and personality live in the private letters the couple exchanged, in the few television dramas and stage plays she acted in and in her (largely unseen) paintings. What would it take to unpack the conditions of her overexposed life? I sift through the remnants of her cultural contributions with an open mind. I’m hoping that her spirit runs through me in the process, that it reveals something about her nature that has, so far, only been hindered.

Felicia dropped Cohn, her paternal surname, to adopt her mother’s maiden name, Montealegre, as a stage name. The second adaptation came through marriage: the day she became Mrs. Leonard Bernstein. In the recent memoir Famous Father Girl, by her eldest daughter, Jamie Bernstein, we mostly read about Leonard, while Felicia’s fears, tendencies and disillusionments are featured in his shadow. The memoir offers valuable insight into their world. The couple had three children, Alexander, Jamie and Nina, and their family life seemed coated with a healthy and jovial sense of humour. In letters, Leonard addresses Felicia as “lovely Goody” or “Mï laü dü.” She signs hers back lovingly, as “Fely” or “Feloo,” and calls him her “Darling Ape.” In marriage, Felicia was free—she became a wealthy woman surrounded by the world’s greatest talents. In her lifetime she met soprano Maria Callas and actor Lauren Bacall, was fast friends with the photographer Richard Avedon and spent time with some of the 20th century’s most influential figures, including Jackie Kennedy and author Boris Pasternak. We know from her daughter’s memoir (published in 2018, the centennial year of Bernstein’s birth) that novelist and cultural theorist Susan Sontag sat by Felicia’s side after her cancer diagnosis, when Felicia’s body was already split by the illness Sontag described in her writing. I picture Sontag (sexy fox that she was) sitting by Felicia’s side, summoned to that depressed bedside by the husband and flirtatiously elaborating on her research into the disease. But Felicia’s world appears to have been somatically private and paced. Contrary to the voice I hear on Bernstein’s “Kaddish,” confronting God, Felicia was not one for public manifestations of personal discomfort. She did not air her thoughts about the disease during Sontag’s visits. Some call that grace; I might call it denial or repression.

At the start of my research, I learned that Felicia was born on February 6, 1922, in San José, Costa Rica. A lot of important things happened the year of her birth: a final attempt to unite Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador failed; the German Social Democratic Party was founded in Poland; President Warren G. Harding installed the first radio in the White House; Stalin came into power; the BBC started to broadcast radio; Jean Cocteau’s play Antigone, with a set designed by Pablo Picasso, opened in Paris; hyperinflation deflated the German mark; and the last confirmed California grizzly bear was killed.

Felicia was the middle daughter of Clemencia “Chita” Montealegre, who came from one of Costa Rica’s most powerful coffee families, and Roy Elwood Cohn. She grew up in Chile, where her father, a mining engineer, was head of the American Smelting and Refining Company. Alfonso Carranza, my grandfather, was one of the 11 children of Adelia Montealegre (Clemencia’s sister) and Jaime “Cheme” Carranza. My grandfather, who was somewhat distanced from the Montealegre family’s extensive wealth (Jaime, his father, died before my grandfather turned of age), was an illustrious, serious and very well-read man. He taught himself multiple languages, and although he didn’t get to finish school, he led a decent life. He drank at the bar with his friends, gardened, and he collected every volume of Reader’s Digest published in his lifetime. He had a picture of a man harpooning a whale framed above his bed. I always thought it was him, holding up the weapon in mid-air. As a child, he spent a few summers with Felicia and the many other Montealegre children at the family’s farm, El Herrán, in Tres Ríos, on the outskirts of San José.

My grandfather treasured his memories from those days, but anytime JFK, musicals or US politics came up casually in conversation, he’d lift an embarrassed eyebrow anticipating that my dad would chime in, jumping at the opportunity to bring up Felicia’s name and their vague connection. This never impressed my grandfather, who was very much a man of his time and limited by his social circle. He was both anti-homosexual and anticommunist, though certainly not wholeheartedly, as my father was both homosexual and an aspiring communist. And anytime Felicia or Leonard were mentioned at our house, the magic of West Side Story descended and my manic father would break into song—“Mariaaa! I’ve just met a girl named Maria!”—and dance my sister or me about the room. It was as though they’d truly been our dear “Uncle Lenny and Auntie Feloo,” spoken just like that, in English. The immediacy of this distant familiarity was a beckoning to our queer acceptance. But it was more than that, this relation. It propelled creativity, endurance and an aspiration for geniality in our household. I grew up singing and acting, taking part in musical productions if only to impress my father, and although I quickly learned to love the stage, I never got used to the attention. For this, I feel kinship with Felicia—leaving home at a young age, not exactly to follow a predicted path but to make an alternate one of her own.

Tom Wolfe’s characterization of Felicia focused on her finesse, shaping her into a cautionary tale of what being new to money combined with having strong ambition could become. He identified this trend as “radical chic,” vilifying Felicia for supporting the Panthers while also being wealthy.

Felicia moved to New York in her twenties to pursue a life in classical music—at least that’s what she told her parents to convince them to let her make the move to the States. She established herself in Greenwich Village and turned to acting; perhaps that was her plan all along, it’s hard to say. She and Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau, who had also moved to New York, were friends (he had been her piano teacher) and it was at a party in celebration of their shared birthdays, at Arrau’s place, that Felicia met Leonard. As an actor, Felicia studied theatre under Herbert Berghof, appeared in a few adaptations of plays made for CBS and even won a television acting award in 1949. Arrau quickly garnered an international reputation, whereas Felicia struggled to establish and support herself as an artist and find continuing work as a young actor. In a letter to Leonard, written from California on February 6, 1947 (a year after they’d met), she writes: “Thank you for your check. The great Montealegre career is at a complete standstill—I am seriously contemplating going back, defeated but healthy! The only trouble is though that I won’t get a job in New York either! Oh shit.”

Felicia never managed to re-establish herself professionally after their marriage, in 1951. Of her television works, only a few—including adaptations of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1950) and Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage (1949), in which she starred opposite Charlton Heston—are available to view online, but the Internet Movie Database lists 14 acting credits on her profile. In the years following her marriage, Felicia also took painting lessons with a few postwar painters and New York–school Abstract Expressionists such as Daniel Schwartz and Jane Wilson. Sadly, these early forays didn’t give her enough credence to be remembered as more than a gorgeous wife and occasional actor, but the longing for a sense of accomplishment never faded. In late 1951 or early 1952, not long after they married, Felicia wrote to Leonard, admitting, “I know now too that I need to work. It is a very important part of me and I feel incomplete without it. I may want to do something about it soon. I am used to an active life, and then there is that old ego problem.”

In Of Human Bondage, opposite Heston, Felicia’s delivery is crude and brutal, almost unwatchable. Her portrayal of a wretched character (Mildred) includes a choppy transatlantic accent replete with over-enunciated syllables. I cannot tell if that is the fault of the era or Felicia’s apt portrayal of Mildred, a social-climbing waitress. Here, I can tell that Felicia tries fastidiously to master English intonations, Spanish being her mother tongue, but she ends up sounding stagey and melodramatic instead of just the right amount of entitled and whiny that’s expected of the Mildred character. As I watch Of Human Bondage, I wonder if Felicia spoke with an affectation in her real life, day-to-day. It’s hard not to picture her, a cigarette in hand, with the other hand at her elbow, paused mid-speech, only to resume over-enunciating words as she practised her lines through the rings of smoke. Was the drawl in the film constructed to reflect an “exotic” identity, one in which the industry no doubt would have cast her? Considering the barriers she might have faced as an actor, one can quickly envision her for what she was: an artist with an avocation, and a will stronger than most.

Felicia’s performances—what can still be seen of them—are not restrained. She uses every inch of her face and seems very conscious of how her tone of speech and gaze affect her delivery. I watch the films again and again. And again, I listen to her eloquent and fierce voice speaking to God in Bernstein’s “Kaddish,” and it overwhelms me.

I want to pray, and time is short.

…Yit’gadal v’yit’kadash sh’mei raba, amen…

Sometime in the year before Felicia’s death, Leonard moved to California with his lover, classical-music radio-station director Tom Cothran, leaving her in New York to deal with the gossip surrounding his increasingly public homosexuality and the aftermath of their broken marriage. In earlier days, anytime Felicia’s social life was threatened, she was able to rebuild it. But her body caught up to the loss, and in 1978, at the age of 56, she succumbed to cancer. A guilt-ridden Bernstein returned to care for her in her dying days. Bernstein scholars have argued that as a closeted gay man, during a time when homosexuality was still criminalized, Bernstein’s knot with Felicia helped him become the music director of the New York Philharmonic, but I wonder how well he understood this himself up until this moment. It’s only through the recent account by their daughter Jamie that Leonard and Felicia’s connection has been given a more complex place, and Felicia’s role in managing the couple’s social-justice efforts been understood as central to the narrative. We will soon see how this all plays out, Hollywood-style, in the upcoming biopic about their marriage, Maestro, in which Bradley Cooper will star as Leonard and Carey Mulligan will play Felicia.

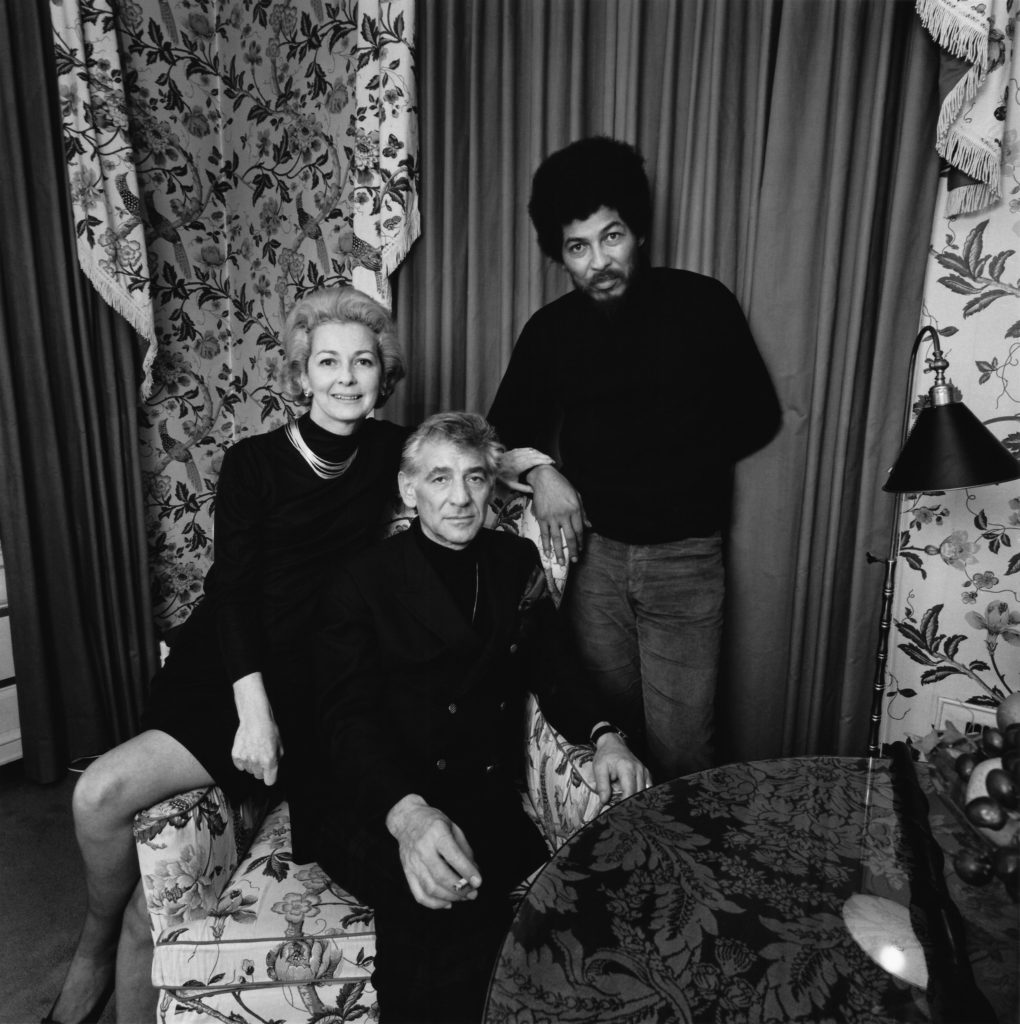

It’s true that Leonard gave Felicia access to a much higher status within their shared bohemian circle but, in contrast to their stylish and creative lifestyle, they also shared leftist politics and concerns for social change. The family lived on Park Avenue until 1974, when they moved across town into a more capacious apartment in the famous Dakota building. The Park Avenue residence was the location of an infamous gathering Felicia organized in support of the Black Panthers on January 14, 1970. The event was intended to raise funds for the legal fees of the Panther 21, and the scandal surrounding it would come to define Felicia’s role as an activist, further obscuring her cultural and political contributions. The Panther 21 were a group of Black Panther members wrongfully arrested and charged in Harlem with conspiring to blow up, among other locations, one of the city’s botanical gardens, and for plotting attacks against police. All 13 members whose cases went to trial were acquitted on May 12, 1971, after what was at the time the longest and most expensive trial in New York State’s history, one that had severe and permanent consequences on the lives of those involved. Many of the accused Panthers were held in “preventive detention”—pest-infested prisons—for months; those who got out on bail sought funds to liberate their friends.

Felicia Montealegre, Leonard Bernstein and Black Panthers leader Donald Cox at a January 14, 1970, fundraising event for the Panther 21. Photo: Stephen Salmieri.

Felicia Montealegre, Leonard Bernstein and Black Panthers leader Donald Cox at a January 14, 1970, fundraising event for the Panther 21. Photo: Stephen Salmieri.

For the cover story of the June 8, 1970, issue of New York Magazine, titled “That Party at Lenny’s,” journalist Tom Wolfe called out the progressive elites of Manhattan for their support of the Black Panthers, arguing that the contrast between their lifestyles and the causes they supported was too stark to be a genuine statement of solidarity. Wolfe’s essay worked to invalidate Black–Jewish political allegiances and ignored Felicia’s role as a committed activist, focusing instead on describing the hors d’oeuvres she served at the party and noting her talents as the diplomatic wife of the “maestro.” While Wolfe mocked Leonard and his friends for their celebrity, it was the cause they espoused that was hit the hardest. This indictment, and the racist coverage of the political activities of the Black Panthers, irrevocably shattered the lives of many Panther leaders. The way Wolfe saw it, New York’s progressive elite couldn’t have homeworkers and simultaneously fight for a good cause. Wolfe claimed Felicia ran a network providing South American homeworkers (he writes that it was known as the “Spic and Span Employment Agency”) for her rich friends (whom Wolfe presumed were too embarrassed to have Black people working in their households during the Civil Rights movement), when in fact Felicia employed South Americans because she wanted her children to grow up speaking Spanish. Wolfe’s toxic characterization of Felicia focused on her finesse, shaping her into a cautionary tale of what being new to money combined with having a strong social ambition could become. He identified this trend as “radical chic,” vilifying the Bernstein family, and Felicia especially, for supporting the Panthers while also being wealthy (as if the two were incongruous).

It’s hard to reckon his view of her with my own version. Or to reconcile how any of the trivialities that surrounded her fortunate life might matter in light of the urgency to protect Black lives that continues today. The Panthers’ demands for Black Americans were clear: full employment, decent shelter, exemption from military service, release from all prisons, trials by Black juries, an end to police brutality and murder of Black people, and education exposing “the true nature of this decadent American society.”

I note them with a heavy heart because these demands remain unfulfilled, and the struggle is continuous.

Felicia’s life was marked by the technologies and access of her time, but she did something with the power and wealth she had at hand to wield. Even in death, being married to a world-famous musician and composer casts its spell, albeit somewhat ambivalently, on her agency as an artist and activist. Still, I am glad she was married to Leonard. I am glad she was able to raise nearly $10,000 for the Panthers. I am glad that as a Jewish Central and South American she did something to transcend the needs of her class, race and status, at times elevating herself in meritocratic fashion but also raising others with her.

I think back on my youth, the many afternoons I spent watching the 1961 film version of West Side Story, that same one in which some of the actors sported brownface to play their Puerto Rican roles as Sharks. I think about the stereotypes it cast of Latine—“I want to live in America,” and so Felicia did. Bernstein didn’t write the lyrics for the script, and I have to remind myself that stereotypes were often the only form of visibility afforded to us then. I sing, “I want to be in America!” and reflect on the fact that even though Felicia was, according to her daughter, white, her maternal origins and adopted culture were Central and South American. I do not doubt she felt European too, and I do not think the choice to have her be played by Mulligan is necessarily a bad one, but the omission of this part of her heritage remains, and I suspect it will be further fumbled, as it was in the essay by Wolfe, where hers is a “tango” smile even though she grew up in Chile, not Argentina. The conflation of all these places and people is something I suspect Hollywood will choose to overlook. Maybe that’s why she’d hoped to make it there as a young actor.

Felicia’s life is well-documented. She was photogenic, poised and smart. She travelled widely (although not nearly as much nor as often as her husband), and it’s easy to look up pictures of her online. It’s easy to vicariously enjoy the places she visited and gawk over the designer clothes she wore. Her manner seems to have intensified with age, rendering her ever more confident (wise, or resigned) in later years. Even though she was born to some of the oldest money you could find in a small country, that access was nothing compared to what she built in marriage. But like many women of her generation, in building a family life, Felicia lost a creative one. Still, nothing is sadder for an artist than being continuously fame-adjacent instead of recognized for their own merits, however small. I see her when I comb through her husband’s archive. The spirit of her words runs through each page.

January 25, 2021: The online version of this Winter 2021 print story has been edited for style and clarity.

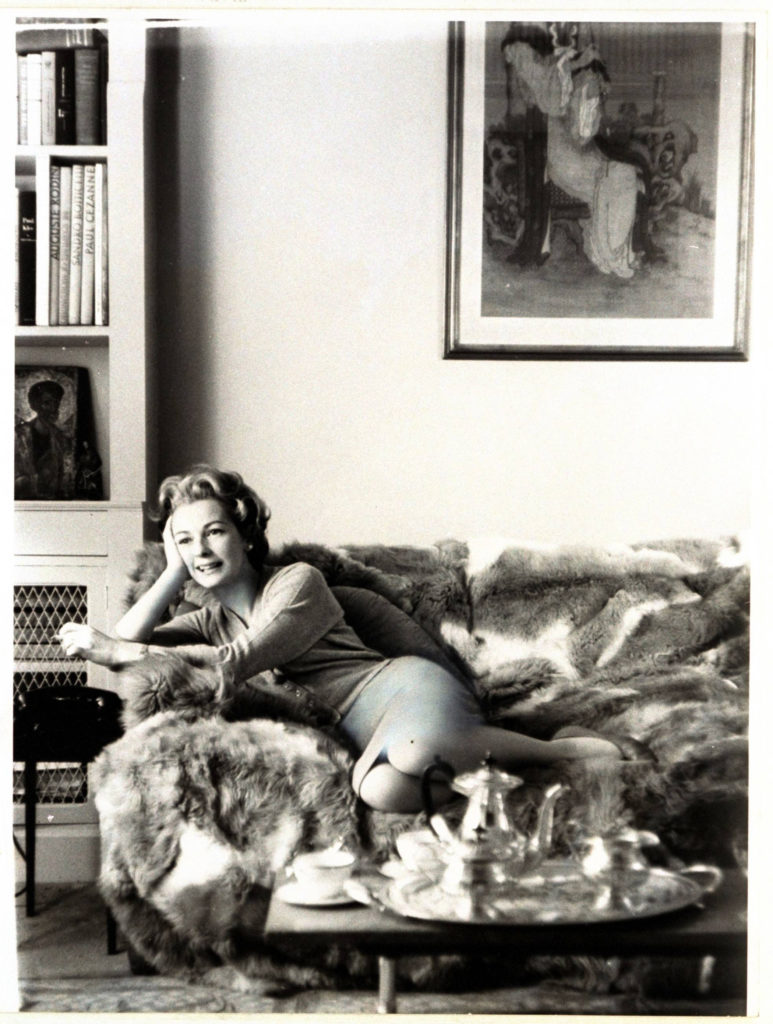

Felicia Montealegre for Vogue, January 15, 1960. Courtesy Condé Nast Collection Editorial/Getty Images. Photo: Henry Clarke.

Felicia Montealegre for Vogue, January 15, 1960. Courtesy Condé Nast Collection Editorial/Getty Images. Photo: Henry Clarke.