Note to the reader: I am using this regular column to think out loud in public about questions and controversies arising from my current research for a book about contemporary Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995.

The first professional opportunities most artists receive are invitations to participate in group exhibitions. When things go well these eventually lead to a coveted solo show.

A solo exhibition is both a mark of recognition and an opportunity to put a focused selection of work before the public. Where group exhibitions allow a curator to explore themes across a range of practices, the solo exhibition is the artist’s chance to demonstrate the strength and depth of their work.

If, as I said in an earlier column, our sense of contemporary Indigenous art was shaped in the 1980s and early 1990s by group exhibitions, it was the rarer opportunity of the solo exhibition that let us see the depth and merit of individual practices.

In that spirit I have made a small selection of solo exhibitions that I hope to cover in relative depth.

While none of the lists I have assembled for this column are intended to be definitive or comprehensive, in this case, with such a small selection, I can’t even claim to be representative. All I can say is that each rewards careful attention.

Jim Logan, Rounding Up Our Children, 1990.

Jim Logan, Rounding Up Our Children, 1990.

1. Jim Logan, “Requiem for Our Children,” Art Gallery of the Whitehorse Public Library (and other venues), 1990

During the short period that Jim Logan lived in Whitehorse—from 1983 until 1988—his art was transformed by encounters with survivors of the state-funded, church-run residential school system. Up until then the dominant influence on his painting had been wildlife artist Glen Loates. The moral imperative to make visible the stories he heard in the Yukon, as he put it to me recently, “gave his art purpose” and demanded a new approach.

Not long after arriving in Whitehorse, Logan, a member of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada, began work as a lay preacher in what was then often referred to as the Kwanlin Dün Indian Village (or “the Village” for short), just outside the city. He remembers being stunned by the conditions at Kwanlin Dün, which lacked the indoor plumbing and running water, that could be found just across the highway in Whitehorse.

As Logan visited families in the community he also began to hear stories about abuse suffered by children during their time in residential schools. Although he had not attended residential school himself, he felt an obligation to do what he could to make the information he was learning public. At this time residential school abuse was just beginning to be addressed in the public sphere and the frank discussion of the sexual abuse of children was especially new and difficult.

The representation of culture-wide traumas like residential school abuse is fraught with moral difficulties. The artist faces a dilemma: attempt to represent an experience that is essentially un-representable or lapse into impotent silence. The challenge is compounded when the artist who has a platform to speak is representing the experience on behalf of others, which is sometimes the case in the immediate aftermath of traumatic events.

Logan hoped that the exhibition would give residential school survivors an opportunity to begin talking about and dealing with their own trauma. According to curator Ruth McCullough, who supported what she saw as Logan’s desire “to honour the stories he heard,” the exhibition of the works in Whitehorse nevertheless “caused a bit of an uproar.”

In a recent phone conversation Logan recalled that at the openings he was able to attend, people tended to avoid the difficult subject matter and simply compliment his technique. He also remembers that white audiences often expressed surprise and ignorance about the existence of residential schools and occasionally questioned the veracity of the stories of abuse.

His artist’s statement for the show seemed designed to break through this resistance, telling non-Indigenous viewers that he wanted them “to live and experience what those children experienced, be it for only a moment. I hope you remember that those children lived it day in and day out.”

It was only when Logan read written comments left by visitors that he found notes from residential school survivors saying they had found the exhibition helpful in exploring their own experiences and coming to understand that they were not alone in what happened to them.

The exhibition itself involved a series of narrative paintings based on first-hand accounts of a range of residential school experiences.

Jim Logan, “A Requiem for Our Children,” 1990. Installation view at the Yukon Art Centre. Image courtesy Government of Yukon.

Jim Logan, “A Requiem for Our Children,” 1990. Installation view at the Yukon Art Centre. Image courtesy Government of Yukon.

The style he chose, with a few exceptions, might best be described as a folksy post-impressionism bordering on fauvism; bright colours applied in flat areas, with subjects given shape by simple black outlines. The simplicity and sweetness of a style that might be used to illustrate a children’s story makes the eruption of traumatic subject matter all the more jarring; a violation of innocence at the level of form.

In Rounding Up Our Children, distraught families gather around a pick-up truck parked on a gravel road running through a northern Indigenous community. It is there to take their children away. In the back of the truck, which has wooden-fenced sides, a black-garbed priest stands calmly checking children’s names off a list. This moment of separation—a mere administrative chore for the priest—is an explicit trauma for both parents and children.

One of the things Logan learned in his conversations at Kwanlin Dün was that parents were wounded terribly by their inability to protect their children. Discussing the situation in 1990, Logan said, “the stories that I’ve heard have been ones of extreme guilt. They wish they could have done something, but it was against the law for them to withhold their children from school.”

Other works in the show depict everything from escape attempts and disturbingly choreographed Christmas celebrations, to, in one case, an explicit scene of sexual abuse. In Night Visit a priest assaults a child in his dorm bed, one hand on his genitals, the other clamped over his mouth to muffle a scream. Hard to look at, but perhaps worse to ignore.

Logan was concerned, however, not to present the children as one-dimensional victims. In Sneaking Lipstick, the dissident agency of several students provides a moment of relief and humanity, as we see a group of four girls gathered in the woods, laughing as they try on forbidden lipstick.

After 26 years, “Requiem for Our Children” still disturbs and still demands our attention—a good reason for it to be remounted and on display now until November 26 at the Yukon Arts Centre.

Jimmie Durham, “Janus and His Double” (installation view at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York), 1992. Photo: via MKHA Ensembles.

Jimmie Durham, “Janus and His Double” (installation view at Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York), 1992. Photo: via MKHA Ensembles.

2. Jimmie Durham, “Janus and His Double,” Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York, 1992

By 1992, Jimmie Durham had already produced a body of work that brilliantly dismantled the colonial ideology of settler triumph over savage Indians, including that ideology’s most recent and insidious device: the romantic idealization of the noble savage. His 1992 exhibition at Nicole Klagsbrun pushed this critique into unsettling (and unsettlingly funny) new territory, satirizing how the economies of authenticity driving both salvage anthropology and tourist consumption might lay traps at the heart of the notion of cultural revival.

If one of the end-games of colonization is a demand for authenticity, then the identity politics of cultural revivalism and nationalism run the risk of, as Durham writes in his essay “The Ground Has Been Covered,” “only reading the lines provided” by an existing discourse of primitivism. Or, as he put it in the essay “Very Much Like the Wild Irish,” “we are … too set up by history … the combination of our grief, pride, and sentimentality with the world’s stereotypes of us might be too heavy a burden these days.”

Entering Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, visitors encountered what Durham described in an unpublished 2006 interview with the author as “…a show about opposites. …on one side of the gallery there was art made by an artist—that was me. On the other side there was work by Caliban, a primitive who wasn’t an artist. His work turned out to be much more popular and sellable than my work.”

Caliban is, of course, one of English literature’s ur-primitives, lurking as he does in the shadows of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In that play, Prospero, a magician and the rightful Duke of Milan, has been deposed and exiled to an island where Caliban is one of the original inhabitants. After Caliban makes a sexual advance toward Prospero’s daughter, the magician enslaves him and uses him for manual labour. Durham found this fictional prototype of the savage other “too good to pass up. I have to be his brother.”

Durham’s first exposure to The Tempest was a performance he attended at the Old Vic while he was visiting London for his Matt’s Gallery exhibition in 1988. The production was directed by Jonathan Miller and the cast included two black actors playing the island’s Indigenous inhabitants: Rudolph Walker as Caliban and Cyril Nri as Ariel. Max von Sydow played Prospero. While retaining the original dialogue, Miller focused the play very directly on issues of colonial relations and their impact on the psyche of the colonized.

The idea of Caliban as a self-doubting “primitive” artist both hating and seeking Prospero’s approval drives much of the critique in Durham’s 1992 exhibition. The apparent schism between artist (Durham) and primitive artist (Durham as Caliban) is also crucial.

Between these two bodies of work was a Janus figure made from lumber and PVC pipe. Attached to the sculpture was a handwritten text by the artist asking the viewer to “please pretend for a few moments that it is actually me, the piece of art, that is talking to you.” The sculpture goes on to introduce itself—“I am a representation of Janus, the two-faced god”—and then celebrate his role in the production and the unification of opposites.

At this point, there is an interjection: “Sorry folks! This is the artist Jimmie Durham interrupting here! As soon as Janus mentioned opposites I could see he was going in the wrong direction. Humans and their gods seem to naturally create opposites-as-a-system.” The exhibition is therefore centred around not a union of a civilized and primitive dichotomy, but its satiric deconstruction.

Durham’s Caliban was represented by his diary, the Caliban Codex, in which we learn, among other things, that he has decided to be an artist. The diary pages were exhibited alongside a series of related artworks in various media purportedly created by Caliban.

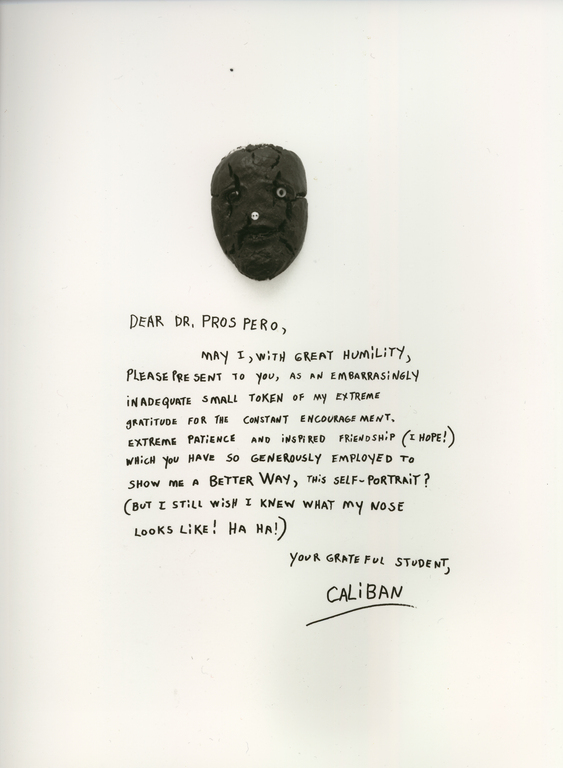

Jimmie Durham, Untitled (Caliban’s Mask), 1992. Photo: via MKHA Ensembles.

Jimmie Durham, Untitled (Caliban’s Mask), 1992. Photo: via MKHA Ensembles.

The diary is filled with a variety of charmingly cartoonish signs of primitivism. Caliban consistently addresses his diary as “dairy” and numbers its “chapters” with one vertical stroke for each chapter (Chapter I, Chapter IIIIIII, etc.).

The diary is a quasi-dissident narrative and Caliban personifies the diary itself as a co-conspirator by addressing it, according to convention, as “Dear” and always writing to it as though it were a friend and confidant. In the absence of real companions, he seems obliged to invent an interlocutor.

In “CHAPTER I,” Caliban notes Prospero’s murder of his mother, the foundational act of colonial violence that Prospero immediately represses with his own ideological explanation: “Dr. Prospero says he killed my mother because she tried to kill him. I was very young then but I know it’s not true. Or at least maybe she had a good reason.”

“CHAPTER II” demonstrates a sibling rivalry between Caliban and Ariel. Caliban wants to believe that Prospero likes or “at least admires me.” At the bottom of the entry, a more likely scenario is suggested as Caliban plays with variations on his signature, creating a series of anagrams before discovering and then immediately disavowing the secret of his name. He writes and then strikes through, “CANIB/,” without completing the A or adding the final L that would make explicit how Prospero’s language has named him.

In “CHAPTER IIIIIII,” Caliban’s crisis of representation comes to a head when he excitedly decides to become an artist. His immediate task is self-representation: I want to make a complete portrayal of myself,” he writes, but the problem is, “I don’t know what I look like. Since Dr. Prospero came there’s nothing here that reflects me. I don’t know what my nose looks like, for example.”

Much of the rest of the diary and the other works associated with it are the product of Caliban’s quest for an image of his nose. In a relief work “Caliban” has attached what appears to be a ragged and bloody animal snout. Above this abject travesty of a nose is the text: “SOMETIMES I MAKE MYSELF LOOK WORSE THAN I THiNK I AM TO SEE IF DR. PROSPERO WiLL COLL CORRECT ME.”

Jimmie Durham, Untitled, 1992. Mixed media, 38 x 25 x 11 cm. Photo: via MKHA Ensembles.

Jimmie Durham, Untitled, 1992. Mixed media, 38 x 25 x 11 cm. Photo: via MKHA Ensembles.

His self-correction suggests (as it self-consciously elides) the complex inter-subjective relationship that the Caliban works tease out, in which one can see Caliban begin to perform his primitivism in the hope that, by mimetic reproduction of Prospero’s image of him, he will be desired and appropriated into Prospero’s world—that is, “collected.”

This is the “primitive” artist’s dilemma and we see that Caliban’s quixotic attempt to depict himself whole has been constantly stymied. He can no longer look past the end of his own nose, no longer see beyond questions of his own identity or imagine that identity outside of his relationship to Prospero.

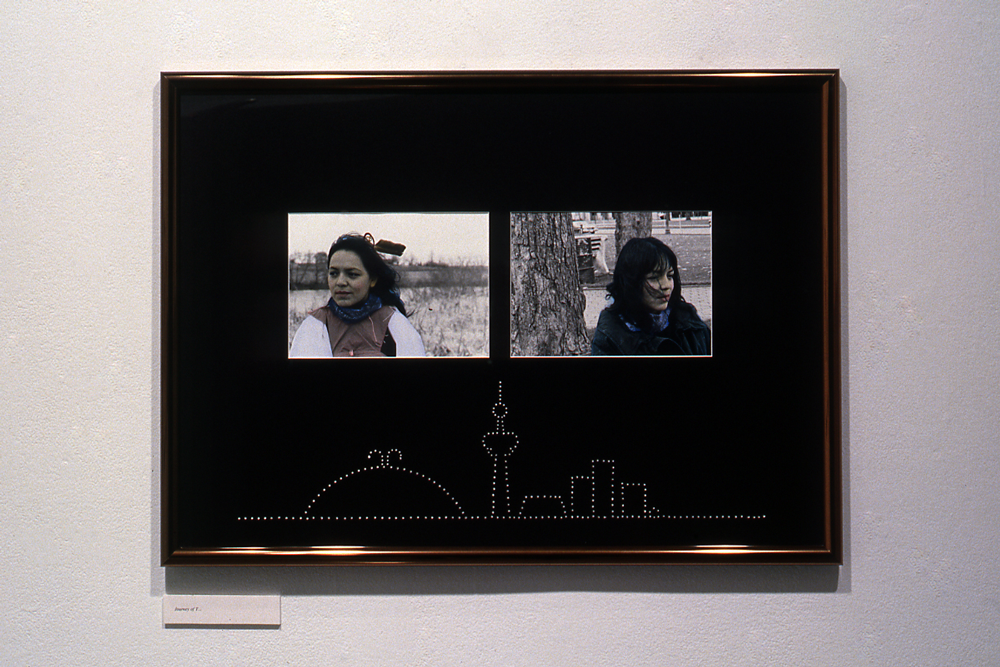

A diptych from Shelley Niro’s “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” in 1992 at Mercer Union.

A diptych from Shelley Niro’s “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” in 1992 at Mercer Union.

3. Shelley Niro, “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works,” Mercer Union, Toronto, 1992

If Logan’s Requiem series gives voice to a traumatic history and Durham’s Caliban works give the alarming diagnosis that evading colonial ideology may be more complicated than it first appears, Shelley Niro’s “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” provides, if not the cure, then a series of strengthening exercise for our capacity for agency.

The exhibition was curated by Carol Podedworny, who was then working independently. It was part of a targeted cluster of exhibitions she proposed to Mercer Union in January, 1991. The first was the 1992 group show “Rethinking History,” which, as the title suggests, tackled revisionist histories; half of the artists in it were of Indigenous heritage.

“Rethinking History,” was intended to provide context for five solo exhibitions by Indigenous artists (not all of which came to pass). In the proposal, Podedworny argued that “the solo exhibition can serve to bring the artists represented before a large and critical audience—something often not possible in the ‘Indian art world’…” At the same time, she continued, the series of exhibitions taken together would provide audiences with a sustained look at the wider issues faced by contemporary Indigenous artists. Niro was the first artist on the list.

“Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” is fundamentally about how burdens of history and identity can be managed and evaded through performative acts amidst the ebb and flow of everyday life. In a review, Lloyd Wong argued that, by drawing on all aspects of her experience, including popular culture, the work pictures “an identity that has to do with lived experience rather than some essentialist or nostalgic cultural identity.”

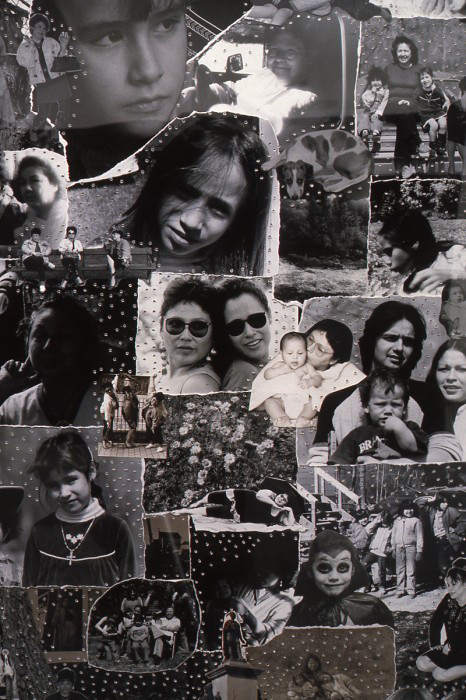

Portraits by Shelley Niro in “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” in 1992 at Mercer Union.

Portraits by Shelley Niro in “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” in 1992 at Mercer Union.

Niro took the photographs that, after some playful framing, matting and hand-tinting, became Mohawks in Beehives because events beyond her control were weighing on her. She said, “It was after Oka and the invasion of Kuwait, and all those terrible, depressing things happening in the world. I find when I get depressed, I work the best because I’m trying to fight off the depression.”

Her solution, as she describes in the exhibition brochure, was a form of serious play: “I talked to my three sisters and I said let’s get rid of our kids and just have a fun day of it–let’s put on make-up and do up our hair, let’s go downtown [Brantford] and have lunch and be really loud and obnoxious.” This all happened before the lens of her camera.

One of the most vibrant of these works is Red Heels Hard, in which a sequence of six photographs of Niro’s sisters dancing and goofing around under a statue of Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant) are framed together within a black matte. Along the bottom of the matte runs a pattern of white dots forming cosmological imagery derived from Haudenosaunee beadwork.

Thayendanegea was a Mohawk leader who fought on the side of the British during the American revolutionary war and, after the success of the revolutionaries, eventually led a large group of Haudenosaunee from their original territory in upstate New York, to a tract of land along the Grand River in Southern Ontario. This would become Canada’s largest reserve, the Six Nations of the Grand River—Niro’s home.

Below each photo of Niro’s sisters is a line from a poem alluding to this journey, which concludes: “We followed that yellow bricked road and clicked our red heels hard, but this is where we will stay forever and for thee stand on guard.” The ruby slippers may not provide the promised return to a mythic place of origin, but if we are busy laughing and dancing in the more colourful land of Oz, perhaps we can take a moment to enjoy that.

Interestingly, the bronze sculpture of Thayendanegea himself has been cropped out of each frame. We know he’s there, but for the moment the artist insist that we focus on these women.

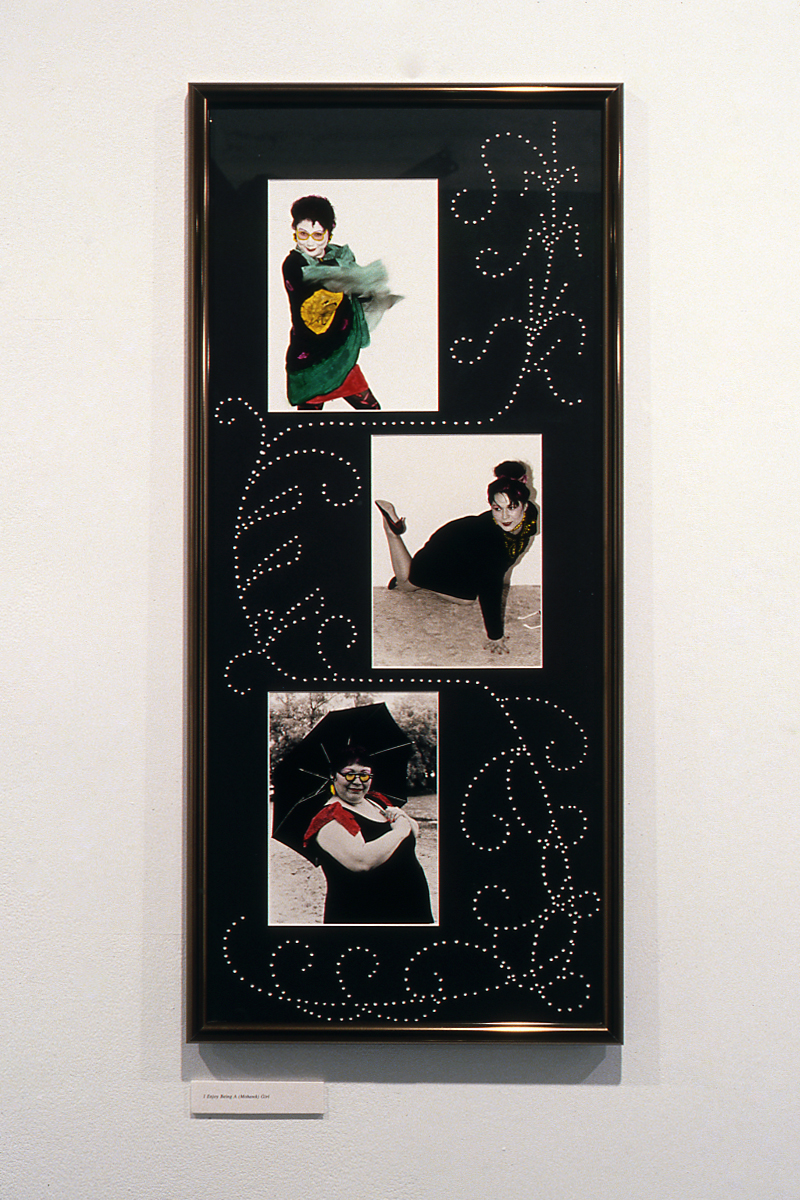

Shelley Niro’s I Enjoy Being a (Mohawk) Girl in “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” at Mercer Union in 1992. Photo: Peter MacCallum.

Shelley Niro’s I Enjoy Being a (Mohawk) Girl in “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” at Mercer Union in 1992. Photo: Peter MacCallum.

Niro was concerned that this sort of playful, pop-culture inflected approach—“a chance to let yourself be free”—too often fell outside the scope of what people imagined as a proper Indigenous identity. This tension is evident in The Iroquois Is a Highly Developed Matriarchal Society, a triple portrait of her mother, June Chiquita Doxtater. (Her mother is also the subject of The Rebel (1987), which I discussed in an earlier column).

The formal ethnographic title is subverted by an image of the artist’s mother having her hair done in an old fashioned hair dryer. We see an image of her laughing, an image of her disappearing under the hairdryer, and then laughing again.

As with Durham’s work, the concern is not simply about stereotypes as an external threat, but how those stereotypes affect the consciousness of the people being stereotyped.

In a conversation with Larry Abbott in 1995, Niro argued:

[A] lot of times Indian people end up stereotyping themselves. They … buy into the mushy, gushy image that is acceptable. …you have to decide what you want to do and you have to ask questions. …am I doing something because it’s expected of me to do, or I am doing it because I really believe this and it’s really a part of me? … If you’re searching for your identity, that sounds kind of hopeless, doesn’t it? It just seems to have a connotation that you’re lost or you’re trying to find your way back to someplace. … Regardless of how Indians are viewed … we still watch TV, we read the papers, we listen to music. There are many other commonalities with the dominant culture that I probably wouldn’t want to live without…

We are left with an idea of culture as the sum of many experiences—including possibly numerous cultural heritages—but also as a performative process of active agency involving selection, transformation and invention. That’s an idea that has never been more timely.

Richard William Hill is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. If you have advice, information, documents or anything else that might help him with his research on Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995, he would be grateful to hear from you: richardhill@ecuad.ca. Thanks to the many people who have already been in touch.

Shelley Niro, “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” (installation view) in 1992 at Mercer Union. Photo: Peter MacCallum.

Shelley Niro, “Mohawks in Beehives + Other Works” (installation view) in 1992 at Mercer Union. Photo: Peter MacCallum.