Imagine closing your eyes and being unable to recall the face of your best friend, or husband or even your child. Where your memories could only be constructed out of actual photographs or images. Where you couldn’t remember what was in your fridge unless the door was open, even if you had just stocked it. Where you had no idea what you were going to paint, until it was flowing from your fingertips.

At 29, Vancouver-based artist Sheri Bakes was living a dream life. The young woman from Nanaimo, BC, had graduated from Emily Carr University with a degree in drawing and painting. She was working on a Master’s degree in art therapy, and training hard to be a part of the Canadian Coast Guard, where she worked part time in the summers.

Then one day after training, Bakes had a stroke and everything changed. She lost all mobility and feeling on the right side of her body, including her tongue. It took eight years for Bakes to learn to bike comfortably and swim without props. Painting came faster, but proved much harder, and not only because Bakes lost mobility in her right hand. The stroke had also caused a rare condition of internal blindness called aphantasia. Bakes had literally lost her ability to imagine.

Sheri Bakes, Day for Night, 2016. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

Sheri Bakes, Day for Night, 2016. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

“The best way to describe it,” explains Bakes, now 46, from the one-room studio where she lives with her three whippets in Vancouver, “is that when most people pack a suitcase, they still know what is in there even when it’s closed. They can see the items in their heads. I have no idea what is in that suitcase unless the lid is open.”

People with aphantasia have no images in their minds, leading to difficulty recalling memories and keeping track of daily life. “I finally had to take all the doors off my cupboards in my kitchen. I kept buying water bottles because I didn’t think I had any. Then I found like 50 bottles squirrelled away in different drawers…. Thankfully you can recycle those…now I just keep everything out where I can see it. It’s a bit chaotic with all the dogs and canvases,” shrugs Bakes, “it’s how I can make it work.”

Bakes has spent the last 17 years developing her unique painting style. One that has no internal image, and no destination before she starts. Bakes “discovers” each in the act of creation.

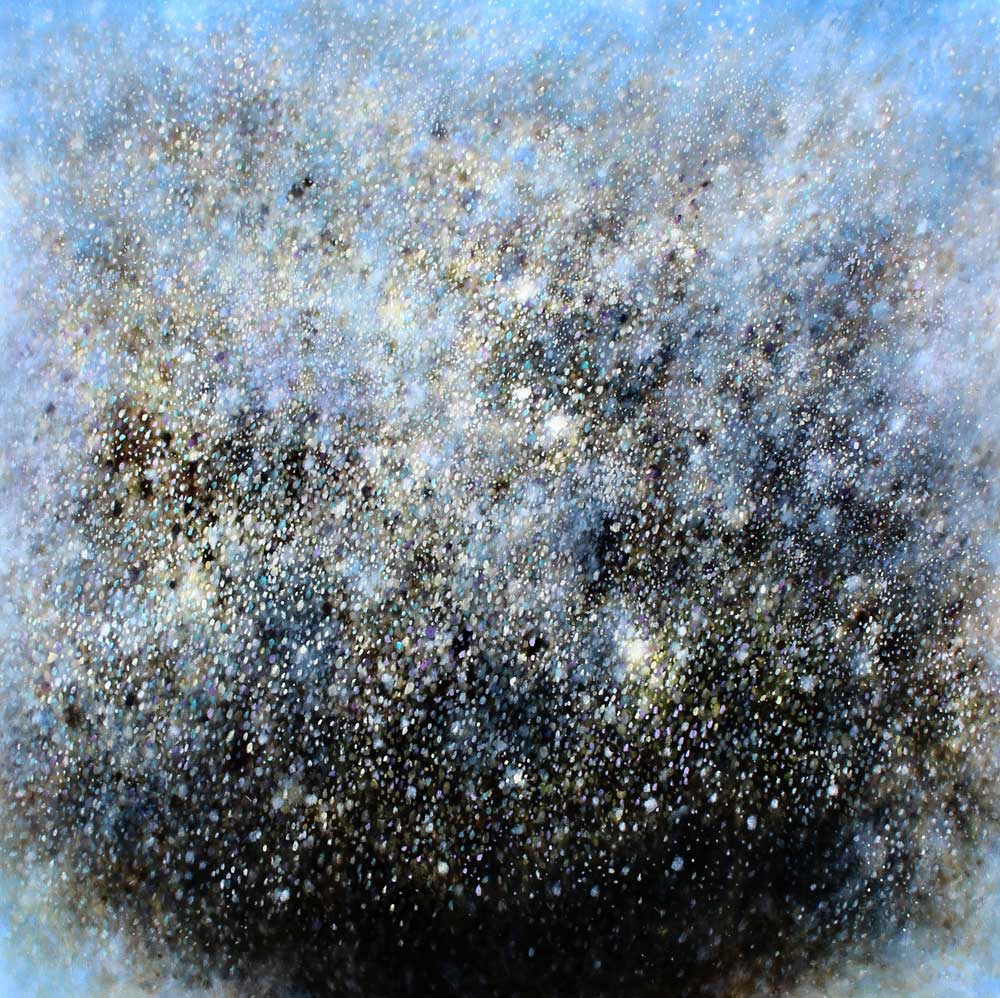

“I usually start with a photo, but the paintings and the photo don’t necessarily end up in the same place,” she says with a wry laugh. For instance, Bakes has just finished a show at Foster/White Gallery in Seattle called “Celestial Navigation.” Each painting is a visceral portrait of the stars, but the photograph she used as her muse is a small picture of cherry blossoms.

Sheri Bakes, Company For The Moon, 2016. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

Sheri Bakes, Company For The Moon, 2016. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

How do you paint when you have no idea where you are going?

“It’s a bit of a free fall exercise in trust,” says Bakes ruefully. “The picture helps, it gives me an image of a feeling I want to express, but really I am finding out what I want to express in the act of painting it.”

Bakes’s paintings are an emotional exploration of the experiences and memories she can no longer access inside herself. “It’s hard for me to grieve, for instance. Most people can bring up pictures or memories of loved ones, and they get to grieve slowly over time. I’ll have feelings that I can’t explain, that I am carrying with me all the time. And then suddenly I will see a picture of one of my dogs that passed away, and all those feelings will converge. It can be overwhelming.”

The difference between Bakes’s pre- and post-stroke paintings is astonishing, almost as if two different people created them.

“Before my stroke, it was all figurative. When I did landscapes, I referred to them as my ‘Sunday Paintings.’ My work was more narrative, more literal, more photo real…and not very good,” Bakes admits laughing. Post-stroke paintings are dreamlike landscapes: small trees fighting valiantly against the wind, flowers letting free their spores in fairy-tale colours and, more recently, galaxies of stars.

“After the stroke, I taught myself to paint before I could even walk or speak again properly; it was the only thing I could really do. I couldn’t carry on conversations, or read, I couldn’t even retain a phone number in my head. I tried line drawing but it made me nauseous within a few minutes. I had always used acrylics before, but trying to get my hand to move—any form of painting—I was just so slow.”

Bakes moved to oil paints because they dried more slowly. She had to relearn to mix colours, because she had lost many of her long-term memories. She basically started art again from scratch. “All I could do was eat, sleep and paint. So there was a lot of painting.”

Sheri Bakes, Celestial Navigation, 2016. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

Sheri Bakes, Celestial Navigation, 2016. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

Within a year of having her stroke, a friend introduced Bakes to Bau-Xi Gallery in Vancouver. Living on a disability income at the time, she was doing paintings on wood that she had found in a dumpster.

“They liked my direction and ideas, but said to keep working and come back in a couple years…but I was determined. I threw myself into painting, and came back again in just under a year with new work, and they liked it.”

Bakes has been supporting herself as an artist ever since.

“I work hard to mask my cognitive disability. How to work around it, and hide it, and fit in.” For years after the stroke, Bakes focused on the things she could no longer do and feel due to her disabilities and limitations.

“Recently, I’ve been thinking that maybe not being able to see things in my mind…maybe that’s a good thing. The paintings have become my brain. The paintings have become the picture inside that I can’t see. I can feel those stars in my chest when I look at them on my wall, and while I am painting them. I can feel them crackling and sparkling. I might not be able to see it in my brain, but at least now I can feel it.”

Amanda Euringer is an award-winning freelance writer who has written for publications from Macleans to the Tyee, on subjects ranging from toxins in the workplace to music festivals. She currently lives in Nelson, BC, in a rambling heritage home with her kids and giant fuzzy dog.

Sheri Bakes, Moonshine, 2017. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.

Sheri Bakes, Moonshine, 2017. Courtesy Bau-Xi Gallery.