On the second floor of the hushed, cathedral-like National Gallery of Canada, tucked inside the entrance to its newest blockbuster exhibition, “Photography in Canada: 1960–2000,” is a small, dimly lit room labelled “PhotoLab.”

Inside is one of the weirdest looking art shows I’ve ever seen. The walls are painted dark grey. The carpeted floor is also dark grey, with a large version of the word “PHOTOLAB” light-projected across its length. Spotlights trained on the walls diffuse a purple twilight throughout the space. One wall hold vitrines with images, and at the back of the room, dark-grey plinths support a cluster of five video monitors, in front of which colourful beanbags serve as “seats.” Touchscreens offer didactic material.

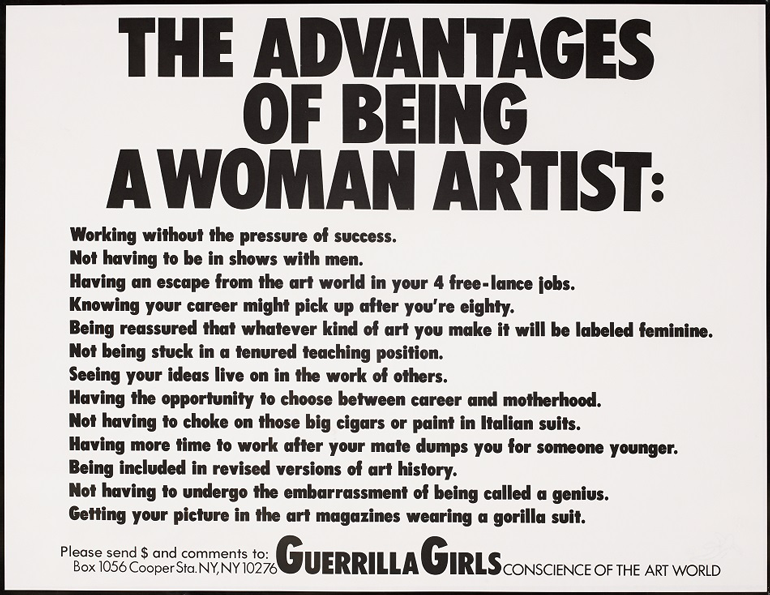

Guerrilla Girls, The advantages of being a woman artist, 1990. Poster, 55.9 x 43.2 cm. National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa. Art Metropole Collection, gift of Jay A. Smith, Toronto, 1999. Photo: NGC / MBAC.

Guerrilla Girls, The advantages of being a woman artist, 1990. Poster, 55.9 x 43.2 cm. National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa. Art Metropole Collection, gift of Jay A. Smith, Toronto, 1999. Photo: NGC / MBAC.

The exhibition is called “PhotoLab 2: Women Speaking Art,” and it’s on view until September 10. As the title suggests, it is the second “PhotoLab” to be held in the space, which was launched last fall by the Canadian Photography Institute “as a venue for smaller-scale revolving exhibitions of a more experimental nature.”

The current exhibition contains 15 works by women, drawn from the NGC’s collection, who use the political act of gendered speech in their work. Through a variety of media—text-based prints (Jenny Holzer), photographs with text (Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson), agitprop posters (Guerrilla Girls) and, most notably, video (Lisa Steele, Mary Kunuk, Shelley Niro, Sara Diamond, Susan Britton, Lorna Boschman)—these artists give voice to their experiences and those of others.

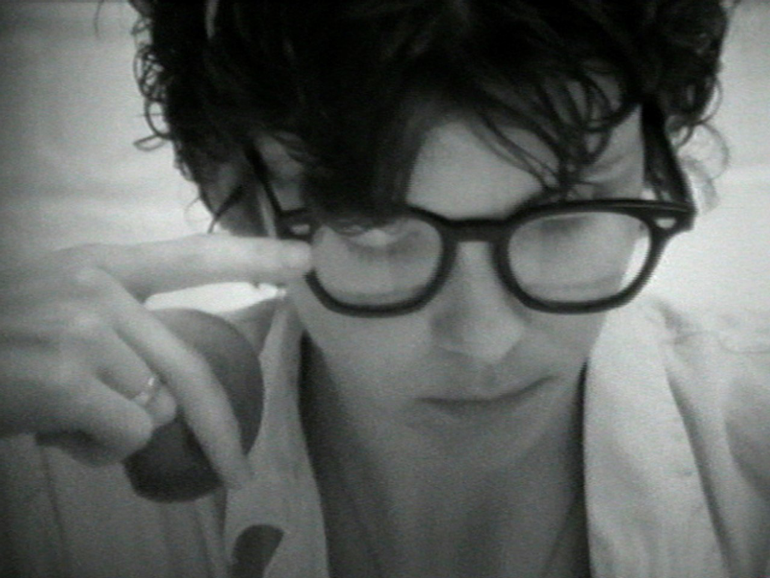

Lisa Steele, The Damages, 1978. Black-and-white videotape, 12:00 minutes. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Courtesy V-Tape. Photo: Lisa Steele.

Lisa Steele, The Damages, 1978. Black-and-white videotape, 12:00 minutes. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Courtesy V-Tape. Photo: Lisa Steele.

The 10 videos in “PhotoLab 2: Women Speaking Art,” which span from the mid-1970s to the late 1990s, are some of the most bracing works in the collection. Artfully chosen and emotionally intense, they offer a welcome survey of early intersectional video work by women in Canada. As the wall text suggests, the selections “expose the numerous political and ideological factors in society that affect individual development, especially in terms of race, gender and sexuality.”

Kunuk’s Unikausiq (Stories) (1996), a set of computer animations based on childhood stories and Inuit folklore, resonates with Steele’s A Very Personal Story (1974), in which the artist tells the story of being 15 and finding her mother’s body. Niro’s parodies of Indigenous stereotypes in Overweight with Crooked Teeth (1997) find a straight-faced counterpart in Diamond’s Ten Dollars or Nothing! (1989), which documents the fish canning industry in 1930s British Columbia. In Scars (1987), Boschman interviews people who cut themselves.

A couple kilometres west, on the other side of Île de Hull, is a low-lying brick structure across from a vacant lot. For most of the last century, it was a textile mill: Hanson Hosiery Mills. Today it’s home to AXENÉO7, one of Hull’s first artist-run centres.

On a clear Wednesday evening earlier this month, AXENÉO7 hosted an evening of films. It was the first instalment of a seven-part series that happens every Wednesday until June 14: “This is Now: Film and Video After Punk,” curated by William Fowler, of the British Film Institute. With titles like “Home Taping,” “Before and After Science,” “Video Killed the Radio Star” and “Entering the Dream Space,” each instalment highlights a different aspect of the post-punk film scene in early 1980s U.K.

Except for a few music videos (meant to satisfy nostalgia), the opening night, titled “Performing the Self,” was aesthetically fresh and cerebral in tone. In Still Life With Phrenology Head (1979), by Cerith Wyn Evans, the narrator recites a passage of Maurice Merleau-Ponty while white rats eat rotten fruit. In John Maybury’s The Modern Image (1979), a young man cradles plaster death masks in slo-mo. In Maybury’s Solitude (1981), successive layers of the self get ripped away one-by-one while industrial jazz grinds on in the background.

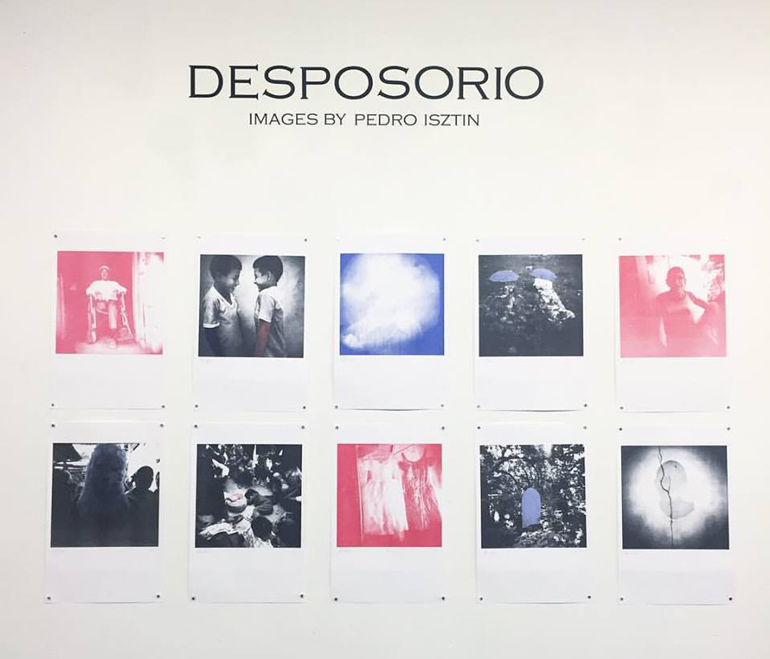

Pedro Isztin, “Desposorio” (installation view) 2016. Courtesy Possible Worlds. Image via Facebook.

Pedro Isztin, “Desposorio” (installation view) 2016. Courtesy Possible Worlds. Image via Facebook.

When I met the photographer Pedro Isztin at Possible Worlds (an artist-run project space, publisher and gallery in Chinatown that’s currently showing his work), he was headed across the Ottawa River, to take photos in the forest. “Desposorio,” his solo exhibition at Possible Worlds until May 28, collects 10 lo-fi snapshots from disparate parts of the globe: a girls’ dress shop in Mexico; a headstone in Hungary; an outdoor cobra ceremony in India; umbrellas sheltering Indonesian graves; identical twin boys in a village in Peru; a man in Tanzania whose head has been overlaid with an image of clouds.

With the help of Melanie Yugo, co-director of Possible Worlds, Isztin has transformed his Holga film negatives into Risograph prints. He’s used only red, blue and black ink, and assigned each colour a symbolic meaning. Red stands for the life force shared through humanity; blue stands for the liminal space between life and death; black is neutral. Armed with an understanding of Isztin’s colour system, the images unfold on a metaphorical plane. I found the twins most intriguing; one is red, the other blue—they signify something more than themselves.

“I ask myself, why would the identical twins be a metaphor for life and death?” Isztin later emailed me. “They mirror each other, essentially they are the same; however, they oppose each other as well. My experience with identical twins is that it’s hard for one to live without the other. Life can’t live without death, and vice versa.”

Jessica Bell, “Fits and Starts” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Central Art Garage. Photo: Julia Martin.

Jessica Bell, “Fits and Starts” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Central Art Garage. Photo: Julia Martin.

Around the corner, you’ll find the Central Art Garage, a converted mechanic’s shop just off Lebreton Street North. When I stopped in to see Jessica Bell’s new solo exhibition, “Fits and Starts,” which runs until May 26, the gallery director, Danny Hussey, was clearing a shipment of wood off the gallery floor. (He runs a frame shop in the back.) A parade of unstretched muslin graced the wall behind him, bearing crisp, flat rectangles of colour on both sides—blue-black, peppermint grey, orange-ochre, vermilion.

Since receiving her MFA from the University of Ottawa a couple years ago, the Vancouver-based Bell has been steadily unravelling the pretense that surrounds the art of painting. She’s worked on both sides of the canvas, has done away with stretchers and has laundered, folded, quilted, stitched, inflated—even made rugs from—her paintings. In “Fits and Starts,” colour is the revelation. Violets, blues, roses and greens now burst from Bell’s surfaces. A massive quilt suspended from the ceiling bears successive layers of sunshine yellow, calling to mind a giant, washy Josef Albers.

Jessica Bell, “Fits and Starts” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Central Art Garage. Photo: Julia Martin.

Jessica Bell, “Fits and Starts” (installation view), 2017. Courtesy Central Art Garage. Photo: Julia Martin.

The other revelation is Bell’s Effort series, which consists of dozens of multi-coloured, snake-like soft sculptures. They’re measured in arm’s lengths and are meant to be handled. On the opening night of “Fits and Starts,” the performance artist Laura Taler, incognito in a black hoodie, walked into the packed garage and wove her way through the crowd. She approached the pile of “snakes” on the floor, and conducted a sort of soft-sculpture ritual, arranging the works and wrapping them around her body. At one point, she stood on a chair and whipped one around like a lasso above her head. As for the safety of the audience, Hussey told me, “If there’s carnage, there’s carnage.”

Rupert Nuttle is a painter and journalist living in Ottawa.

Sara Diamond, Ten Dollars or Nothing!, 1989. Colour videotape, 11:45 minutes. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Courtesy V-Tape. Photo: Sara Diamond.

Sara Diamond, Ten Dollars or Nothing!, 1989. Colour videotape, 11:45 minutes. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Courtesy V-Tape. Photo: Sara Diamond.