After 40 years we should have a different view of the late 1970s Toronto art scene than it had of itself.

Indeed, if it even had a view on itself: it was so busy creating a scene that there was no time for writing its own history. Now, when we have no art scene, we historicize. And it is exactly that late ’70s art scene we look at to do so. But still we think about what the past thought of itself rather than see it from the point of view of the present.

History is cruel. History is not one thing after another: a secure narrative chain unfolding itself to eternity.

Over time, radically new narrative paths open up, but they do not simply present themselves; they must be conceived through historical writing. Simply stated, it is our job now, before we move on and someone else does the same to us, to establish what was important and what was not.

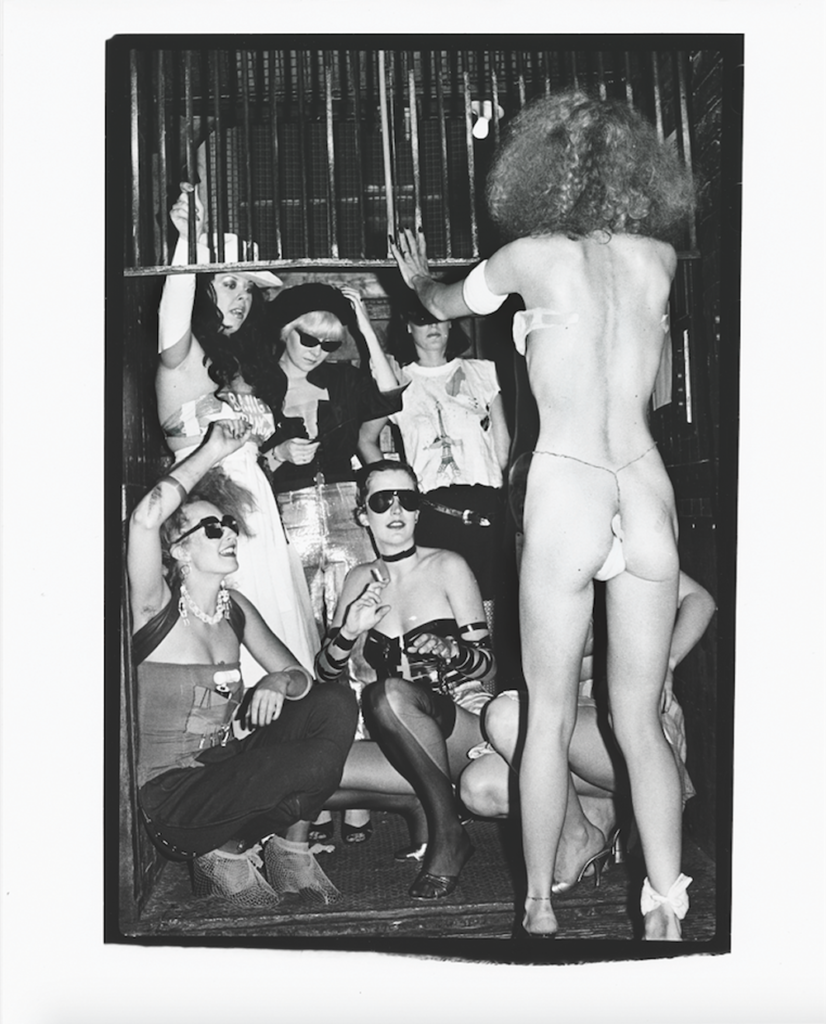

In writing Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene, I discovered for myself, not knowing when I began, precisely what composes this story. It begins with a lost history of feminist performance, such as Glamazon (1975), organized by Dawn Eagle and Granada Gazelle (a.k.a. Miss General Idea 1969), for which David Buchan was the stage manager. These strategies changed gender and transitioned to queer male artists when performance principles were subsequently applied to photography—but not just any photography. Photography allied itself to semiology in this period, when its images were beginning to go big, in influence and size (and also being disseminated through artist magazines like FILE).

David Buchan was one of the artists who invented 1980s appropriation art in Toronto, Philip Monk notes. Buchan also produced campy videos including 1978’s La Monte Del Monte’s Fruit Cocktails (from Tele-Performance). Image courtesy Art Gallery of York University.

Roland Barthes was still the possession of the camp cognoscenti. There were camp principles, but they applied to straight artists, too—Ian Carr-Harris, for example—as well as General Idea, so much so that you could say “camp conceptualism” ruled Toronto art. It was embodied and gendered, and dealt with codes and the transgressing of them. Toronto’s conceptual art was performative.

Then there was what I call “Toronto talk.” Talk was the theatricality of Toronto art. Language was attracted to the image as talk, and together the two were seen to be a frivolous performance. How did such degraded art-scene entertainments—of media parodies and inhabited popular cultural formats—become the main show of Toronto’s art history?

It was no triumphant progression for the downtown Toronto art scene. Camp was contested at the time by the macho rigour of phenomenological sculpture and the vacant prettiness of colour field painting, which were the privileged purview of uptown commercial galleries and the Art Gallery of Ontario. Most of all it was opposed by the decade’s political orientation in art—of the Red Guard, Marxist-Leninist variety of strident polemics and sometimes good graphics. Ultimately, the fashion for politics and the posturing of performance were all one pose, which may have irked the former “moral” artists when they unselfconsciously utilized the so-called frivolous strategies of the latter.

Whatever New York likes to think, 1980s appropriation art was invented in Toronto by the likes of General Idea, David Buchan and others when the practice was called inhabitation. What made Toronto unique? Well, it was partly that New York no longer had authority in the mid-1970s, and communities could temporarily go off to create their own scenes, usually in the unregulated edges of downtowns where no one was officially watching. Artists were, though. And by looking at one another, and participating in each other’s artworks (again something unique about Toronto), they created the fiction of an art scene and instituted it at the same time by these very means.

They talked in the bars and argued, especially in the slew of newly available (courtesy government funding) artist-edited and -produced magazines (Impulse, FILE, Only Paper Today, Strike), where character assassination was an art, too. Conviviality and contestation made the Toronto art scene at a time when Canada’s vaunted artist-run system was in turmoil: with a palace coup at A Space in 1978 and the closure of the radical Centre for Experimental Art and Communication that same year, when it advocated kneecapping Red Brigade–style and consequently lost its funding.

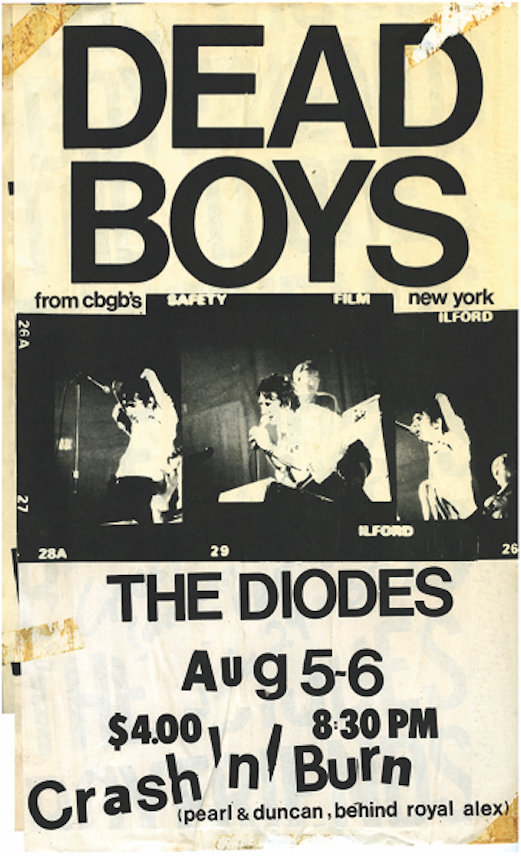

Punk’s destructiveness mirrored the wide-scale demolition of factory and warehouse buildings housing Toronto’s downtown art scene, Philip Monk writes. “Sophisticated artists recognized punk’s strategic value and co-opted its violence,” Monk writes. Image courtesy Don Pyle. Poster design and photos by Ralph Alfonso.

Punk’s destructiveness mirrored the wide-scale demolition of factory and warehouse buildings housing Toronto’s downtown art scene, Philip Monk writes. “Sophisticated artists recognized punk’s strategic value and co-opted its violence,” Monk writes. Image courtesy Don Pyle. Poster design and photos by Ralph Alfonso.

New social movements were in formation at a time when the art and punk/new wave music scenes intersected. The unaligned Cabana Room, run by video artist Susan Britton at the Spadina Hotel, was as important as any art gallery, and CEAC had the basement club Crash ’n’ Burn, which became Toronto’s punk epicentre when it broke in the summer of 1977.

In its own way, punk was influential, too. Its destructiveness mirrored the wide-scale demolition of factory and warehouse buildings housing the downtown art scene. Sophisticated artists recognized punk’s strategic value and co-opted its violence in order to transition from the hippie sentimentality of the early 1970s to the suave new wave irony of decade’s end.

Curiously, the socially transgressive alignment between punk musicians and downtown artists was happening precisely at the moment when punk was being academically examined as a subculture, notably in Britain by the likes of Stuart Hall’s Birmingham School and Dick Hebdige.

Subcultural theory came out of the sociology of deviancy. Artists could teach punks a thing or two about that. Really, didn’t the Toronto art scene itself have all the characteristics of a subculture, with its own protocols of belonging and negotiation of the dilemma of visibility? Too much visibility, in fact, and that’s when the police come. And they did.

This is an article from the Summer 2016 issue of Canadian Art, related to Phillip Monk’s book, Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene, released in April 2016 by Black Dog Publishing. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your mailbox before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.