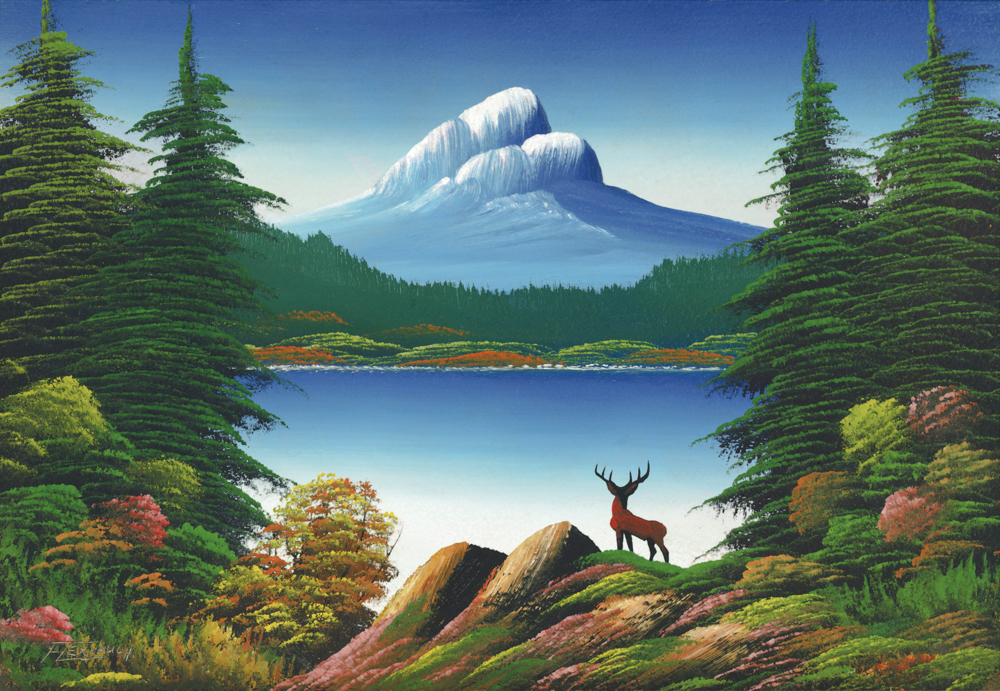

The story seems familiar enough: beginning in the 1930s, Levine Flexhaug began roaming across Western Canada, peddling his wares. But Flexhaug was not an average travelling salesman—rather than hawking miracle creams or toasters, Flexhaug dealt in paintings. Or, more aptly, a painting, which he replicated hundreds and hundreds of times. During his career, which stretched beyond two decades, Flexhaug repeatedly produced this landscape scene, a rendering of a tranquil lake framed by mountains. There were, admittedly, variations. At times the scene included a cabin, occasionally a canoe, a single animal, or perhaps a blasted tree or a waterfall. But, to a less-discerning eye, these pieces were effectively the same. Now, “A Sublime Vernacular: The Landscape Paintings of Levine Flexhaug,” opening at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina, is lifting Flexhaug out of history’s footnotes, and, in the process of fleshing out his story’s odd blend of midcentury kitsch and earnest passion, underscoring Flexhaug’s surprising legacy on the painting of the prairies.

Flexhaug was born in 1918 on the family farm outside of the small town of Climax, Saskatchewan, and it’s unclear where his inclination toward art began. Nancy Tousley, co-curator of his exhibition along with Peter White, admits as much. “He was a farm boy with no education who decided, for reasons I have no knowledge of, that he wanted to become a painter,” Tousley explained. Beginning his career in Climax in 1938, Flexhaug started out by setting up shop and studio in front of the dry goods and hardware store on Saturdays. “Flexie,” as he became affectionately known, “would paint outside and sell works as he painted them,” explained Tousley. “He was a speed painter.” His business expanded—Flexhaug began painting at summer resorts at lakes in Saskatchewan, eventually moving around through small towns in Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, making and selling versions of his signature scene.

Painter David Thauberger, a Flexhaug collector and enthusiast, first introduced Tousley to Flexhaug’s work. “I don’t think we would know of Flexie had he not been collected by artists,” explained Tousley. “That’s how I first learned about him, that’s how Peter White first learned about him. I got my first Flexie from Chris Cran, and David Thauberger gave me my second—and they found them at Value Village.” Flexhaug’s standing, as a painter’s painter, appealed to Timothy Long, head curator of the MacKenzie Art Gallery: “One of the main reasons we took the exhibition was our major exhibition of the work of David Thauberger, who has shaped the parameters of Canadian landscape painting. David has described his work as an attempt at ‘genuine simulation,’ and you see that Flexhaug is one of those artists whose work is formulaic, but feels genuine at the same time. It’s a quality that David picked up on, and it resonates with a surprising number of artists.”

Though Flexhaug’s works can be spotted in Value Villages, it would be a stretch to consider him an outsider artist. His composition, in particular, evinces an awareness of art history. “The iconography is right out of the picturesque tradition,” noted Tousley. “I’m not quite sure exactly where he came in contact with it, because it was everywhere. It was a pictorial tradition that people were familiar with. What he did was stylize it, and rendered it quite beautifully given the limitations within which he worked.”

Tousley and White plan to capitalize on Flexhaug’s stylistically irregular work within the show. “It really is an installation rather than an exhibition design that you’re used to seeing,” said Tousley. Installed across three galleries, the 467 works will be hung in a largely continuous band across the walls, with a three-foot horizon line above the floor, above which a grid of paintings will be arranged. It’s an approach that Tousley and White hope will emphasis the breadth and consistency of Flexhaug’s output. “Every painting is quite fresh,” noted Tousley. “There is very little about them that is slap dash.”

And so, more than 40 years after his death, Flexhaug, the travelling salesman of Canadian art, has finally been given his big solo exhibition—an outcome that even Flexhaug himself couldn’t have predicted. But perhaps the story shouldn’t be quite so surprising—despite Flexhaug’s handmade mass production, his work transcends its circumstances. “The individual works have a strong sense of appeal as paintings,” said Tousley. “They were made at a time when people were in fairly dire straits living on the prairies. They gave people a haven, a mental resting space that could be quite comforting.”