Maskull Lasserre is the Mike Tyson of the Canadian art scene: a soft-voiced killer with an unstoppable left-right combination. On one hand, he seems like the sweetest, most unassuming person you’re ever likely to meet. On the other, he’s the maker of spellbinding, disturbing objects of steel, wood, bronze and stone, powerful ciphers for our time that are loaded with meaning, unspoken violence, ironic tragedy or, sometimes, a delicate wonder. Plus, within minutes of my walking into his studio, he’s trying to get my head into a guillotine.

“You’ll see. It’s super peaceful,” he says with a sly smile, recounting how a curator who recently interacted with this piece—one of his recent pieces, a working guillotine with the handy-dandy dual purpose of turning into a stretcher to carry away the results of its mechanism—broke into an irrepressible monologue about all the things she wanted to do before she died. I know one thing I want to do: keep away from that guillotine. With a curl of his lip and a dramatic SCHLINNNGGG!, the artist lets the heavy blade drop into its empty slot, sending shivers down my (luckily still intact) spine.

I first met Lasserre just five years ago, when he was but a lad in the last leg of his MFA at Concordia University in Montreal, his current home. He was born in Calgary but lived in his mother’s native South Africa for part of his childhood, moving back to Canada, to the Ottawa area, when he was six years old. His South African heritage explains the slight inflection in his speech and his ability to describe the particular stench that snakes have. “You know, that signature reptile smell?” he asks as he shows me one of his intricate carvings, the neck of an axe he’s shaped into a snake’s spine. I sadly admit ignorance and he says he smelled that scent throughout the carving experience, hinting that there’s an alchemical aspect to his striking body of work.

His themes are what he terms “elemental,” which partially explains their dramatic appeal. Lasserre examines death, music, literature, beauty, pain, purpose and integrity (both structural and philosophical) through eerily complex representations of transformed tools, skeletons and animal parts that indicate a mastery of welding, forging, mechanical engineering, musical-instrument design and weapons making. Some of his pieces have incredible heft—he builds full-size pianos—while others are fragility embodied. One recent work, Murder (2012), features 19 crows and ravens he sculpted out of wood and then charred so that they disintegrate at the merest touch. It was exhibited in a group show at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design earlier this year, along with a work by Andy Goldsworthy. The boy has come a long way in five years.

Isa Tousignant: When I met you, you were still in your 20s, but already your graduate exhibition had incredibly complex pieces in it—I remember a massive steel keyboard-less piano, for example, that viewers had to drag across the room to make sound. How, by then, had you learned how to build such things?

Maskull Lasserre: It’s something I am kind of self-conscious about, but I really enjoy reinventing the wheel. I am sure if I were smarter or had a better-articulated plan I could have apprenticed with someone who actually knows how to do these things, and I could have learned things the proper way. But I think what’s nice about sorting things out for yourself is sometimes you take roads that you don’t know not to take, and you make interesting discoveries along the way. That’s really what I am interested in—that process of learning and developing things basically from the ground up. It carries with it not the sense of knowledge or consciousness that’s been parachuted in partway through the process—it really has the sense of something that’s been developed from scratch. It has that lineage or ontology that makes it feel sincere in a way it wouldn’t if it were more predetermined. It makes the experience more interesting in a selfish way for me.

IT: Isn’t that mostly what making art is about? About the maker having fun?

ML: It definitely keeps me going. I did my undergrad at Mount Allison University, and I was very fortunate to be granted the space, time, materials and tools just to make an ungodly mess and learn from that. That’s very much the way I work: I make a mark and think about it later.

IT: Did you do set building in school?

ML: I did a little bit in high school and in university for the Windsor Theatre—I guess all these things filter in. The notion of a prop and how it participates in this fictional reality that’s laid out in front of people, I find that very interesting.

IT: Also, the false-tool aspect—you often work with the idea of counterproductive devices or booby traps.

ML: Yes. But what I find myself allergic to with regard to theatre props is the faux-ness of them. When I’m making those instruments I try very hard to be as authentic about it as possible. I stand in the role of the actor rather than in the role of the prop maker. In terms of trying to be the luthier or the weapon maker, I make it as sincere as possible. I am disappointed by work that has a resolution floor, work that, if you look at it closely enough, falls apart and the suspension of disbelief is ruined. I really work very hard to make authentic objects all the way through.

IT: So, in your violin-slash-rifle combos, are they actually working firearms?

ML: Yes.

IT: They can kill if you load them?

ML: Yes.

IT: And the guillotine work, it’s really sharp enough to cut off a head?

ML: Yeah. I’m dying to try that thing! It’s my retirement policy.

IT: Where do the musical instruments come in?

ML: I played the violin for 14 years. I was committed but mindless about it, if that makes sense. My mom, especially, introduced me to it, and it was challenging and difficult, but also a tremendously satisfying, rewarding thing—there’s this bodily experience that happens between you and the instrument. But I am doing the same thing today, just with different tools. The notion of synesthesia is very interesting to me. The ability to experience something with another sense than that for which it’s intended—just that feeling of playing the violin and creating something that emerges from the paraphernalia or the mechanism or the tool that you’re using—it’s very much the way I interact with the world around me. It comes from that experience and aesthetic of playing an instrument.

IT: And the physicality of it?

ML: It’s true, but that aspect was subconscious until I started boxing. The thing that boxing allowed me to discover about the violin is that physical relationship. Boxing is also very sound oriented; you don’t realize that until you do it. It has a lot to do with rhythm and choreography.

IT: For how long have you been boxing?

ML: I boxed for about six years. Physically, it’s a really interesting activity. It’s this elemental thing, in a similar way to music. All of the fluff that gets layered on top of human interaction is stripped away and it’s just two guys hitting each other. But at the same time that reveals fascinating things about this hidden delicacy, or the intimacy, of a fight.

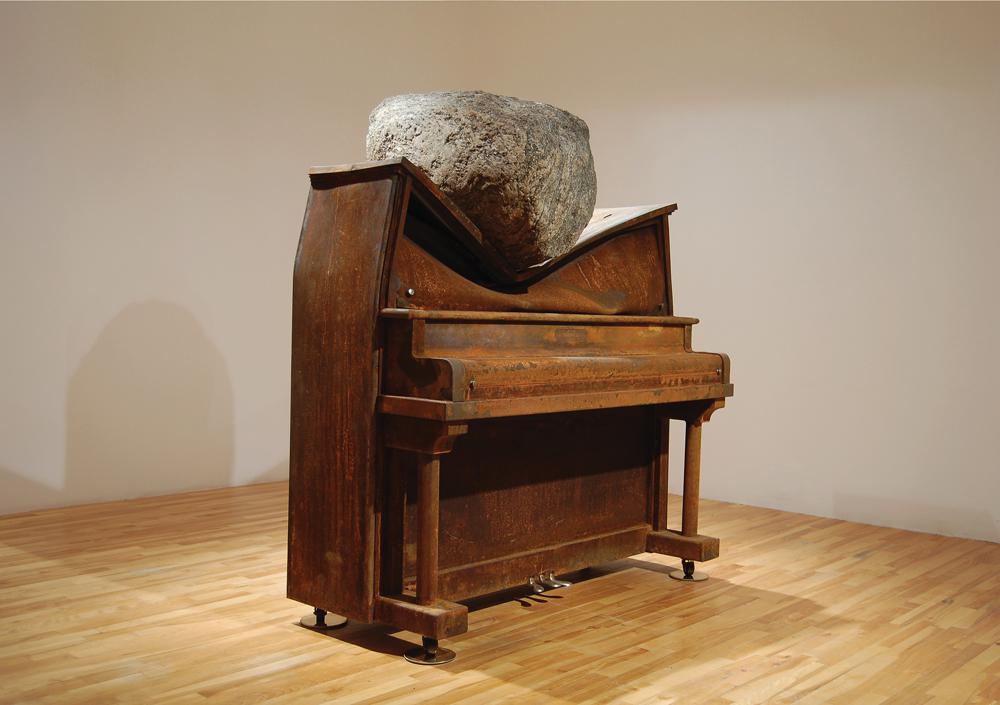

IT: The mass of things: you do very fine-tuned work with your carvings and string instruments, but you also have those piano works that are massive and bulky and superhuman, like the piece exhibited recently at Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain in Montreal, featuring a steel piano whose upper portion was pounded in by a gigantic boulder. What’s the attraction of big things to you?

ML: I think I like to struggle. It lends an authenticity to the work. Not the physical mass in a boastful way, but just the effort that’s requisite—it implies that you really mean it. It’s not something that happens as a trifle or as an accident. It’s something that just by virtue of its physical presence has intentionality behind it. That piece with the piano and the rock is called Coriolis (2011)—that’s the scientific name for an inertial force that explains why falling objects in the Northern Hemisphere actually land slightly to the east of where they were dropped. This piece was just an elaborate satisfaction of my curiosity—how would my welds hold up if tested to that extreme? The only way to test what happens when you drop a thousand-pound boulder on a steel piano is to do just that.

IT: So you really dropped the boulder?

ML: Yes.

IT: How on earth did you get it high enough?

ML: I’m lucky to have still-loving parents who have a bit of property in the woods in Gatineau. Two maple trees were conveniently close together; I spent four days climbing up there, because I had to get about 60 feet up in the tree to build a bridge, and use all kinds of rigging to get the rock up. Fortunately, the rock I found was uphill from that site, so I rolled it down. The staging of the event was the most time-consuming thing, compared even to the welding of the piano. There’s something really satisfying in the fact that the event of dropping the boulder took 0.4 of a second.

IT: What of artists who conceive these crazy scenarios but hire construction teams and welding teams and studio assistants to manipulate the actual objects for them?

ML: The only relevance I have to my work is in the making of it. These things aren’t fully formed ideas as they’re happening—I grow through the work as it’s evolving. I couldn’t think of excluding myself from that process, because without that the work wouldn’t be. I don’t ever make anything that I understand. Something that I understand doesn’t need my intervention—it has completeness in my mind and it is what it is. But it’s the things that are unclear but resonate, those are the ones that need to be coaxed along and developed. I’m just the conductor who moves things around until they come to some resolution.

IT: When did you start carving?

ML: In about 2000. There’s a humility to carving that I enjoy. It’s so intuitive. There’s no magic; there’s no smoke and mirrors; there’s no technology involved. It’s immediately obvious what happened and how it got there. It’s accessible that way, and at the same time it’s extraordinary. There’s a sort of alchemy that happens there. One characteristic of how I work is to dissolve the boundary between tool and sculpture. That kind of mystery and ambiguity between things is the realm I find most fertile—because I end up carving into the tools that I use. It’s a funny kind of reclamation of the object, for its matter as opposed to its use. To some extent, it’s the same with music and instruments—I find it interesting to take mechanisms for music or for performance and transpose them into the realm of static work or contemplative object. Something happens when you move across that boundary.

IT: So, the steel piano under the rock—you built it from scratch?

ML: Yes, I did.

IT: It can be played?

ML: No, it’s just the structure, without strings—though one could install the mechanism and it could work. It would be a challenge to do that now, but it could be done!

IT: The sound box you built at grad school—that has strings.

ML: Yes, that one is everything that a piano is, but without the keys.

IT: And you were never taught how to build a piano; it’s just something you picked up?

ML: My dad was a research scientist for the Canadian government, and, for as long as I can remember, he was very good at bringing home pieces of equipment for me to tinker with and take apart. I really enjoyed the mechanical knowledge that can be gleaned from taking apart teletypes and these other pieces of early computer equipment. I’ve always kind of done what I do; it’s just that the things at the end of my fingers have changed.

IT: Since you started with teletypes, it’s remarkable how un-technological your work is. Pianos and violins are complex creations, but they’re incontrovertibly analog.

ML: When bridges started being built in a serious way, for the first time in history it was suddenly no longer possible for a single human being in the space of his or her lifetime to understand or learn everything that was requisite to build a bridge. Up until that point, with a violin or a piano or a sword or armour, although the information was passed down from one generation to the next, it was possible for one person to know everything that was required to make them. But as soon as bridges happened on the scene, suddenly you needed lifelong experience in, say, engineering or metalwork, and so forth. So now you have these little glass-and-plastic devices, like your iPhone, that engender vertical fields of knowledge that it would take generations to absorb, and there’s an opacity to that. They’re magical. I’m not interested in magic. I’m interested in understanding things and having an experience, because that’s somehow where meaning comes from—from that lived experience.

Discover more artworks by Maskull Lasserre at canadianart.ca/lasserre.