When Sojourner Truth Parsons tells me she’s “so sincere, very sincere, super sincere, overly sincere,” I believe her. Partly because she’s Canadian, and partly for the way she handles her dog, Toni, a spritely blonde who lolls feline in her arms, and totally, I believe her, because of her voice. With a slight lisp, Parsons’s voice volleys over words; it’s sweet, like melon scooped with a spoon tailored to ball the fruit; mother and child, sorrow and hope, conviction and apprehension all wrapped up in it.

In Los Angeles, people talk big. Lie is the law, gossip, gospel. It’s a survival strategy, listening for subtext. What’s beneath, usually, is desire. People still come to LA to make dreams come true.

Parsons’s dreams, while modest by Hollywood standards, are most ambitious. She wants “to be the best artist that I can be.” This is to be a lifelong pursuit. “Art is just what I do,” she says. Now, at 32, the British Columbia–raised creator, who has Mi’kmaq and African Canadian heritage, is committed: “It’s a relationship,” Parsons insists. “Better than any love affair! (When it’s good.) My art practice is my family. I wonder at what age I’ll be when I feel like it’s coming from my vagina.”

She’s patient. As Parsons and I walked, on magic-hour Monday, along LA’s dry riverbed (her choice setting, Toni digs it), the artist mused that what professional success she seeks may not land for decades. She projects herself as a woman revered solely in old age.

“Your work is strange, meaningful, and you’re feminist,’ she says, parroting that status. “You’ve struggled, now here’s your place. That’s the kind of success I yearn for.”

Like Louise Bourgeois? I ask. “Betty Woodman,” she rejoins.

With Ontarian politesse, I suggest that maybe Parsons could expect more—that such late expectations exist for women artists because of capitalist patriarchy, that precedent and ongoing, though crumbling, reality.

Parsons agrees: “You can’t let this misogynistic system define your worth.” But because she needs to make art (“If I’m not, I feel dead”), Parsons rests in this peace of mindfulness: “You don’t have to arrive by anyone else’s standards to feel that you are able to be here, doing what you’re doing.”

Parsons paints daily. Since moving to Los Angeles from Toronto in March 2015, she’s on a roll, receiving enough to continue to buy materials and paint. She’s shown at Toronto’s Cooper Cole, New York’s Tomorrow and LA’s Phil and Night Galleries.

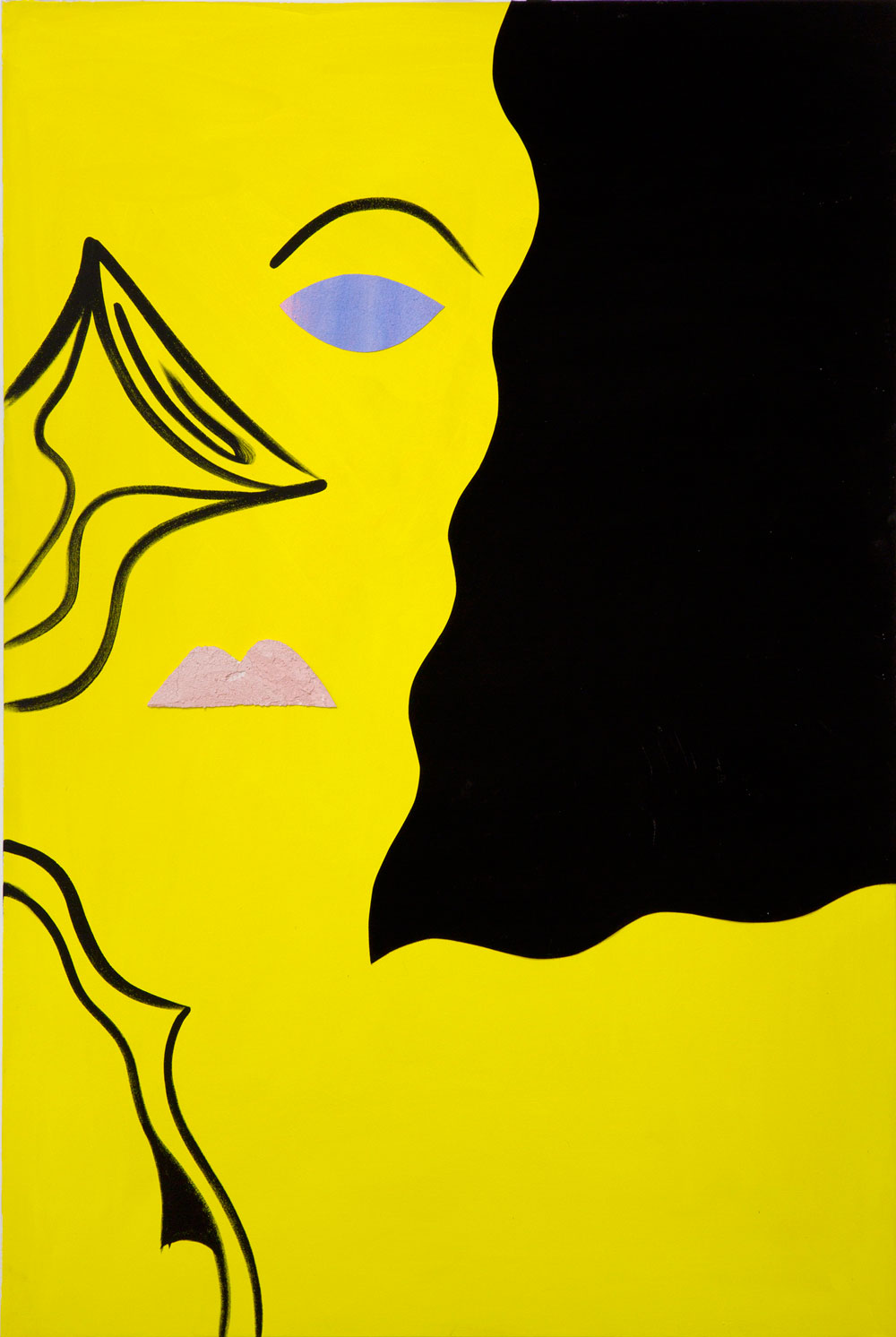

The works is delicate and hearty, like her voice. On a recent canvas, the hair of the figure is brushed so faint, like water on sunned concrete, it seems on the brink of fading out of sight. In other works, minstrel Mickey Mouses knock knees near Betty Boop–wish full moons who’re multiply impaled by fingers and lift their likenesses like dumbbells.

In one of my favourites, money is gunky. American dollars, or Canadian twenties—green bills, in thick acrylics: jaded, forestial, bluesy and phlegmatic—fight for space as a lone grey glove reaches to collect.

It’s rare cool-tones work from an artist who paints, usually, hot and dark, “from the heart.” A vision, I feel of commercial expectation; as in our conversation, Sojourner parsed truth out of it.

This spotlight article, adapted from the Fall 2016 issue of Canadian Art, has been generously supported by the RBC Emerging Artists Project.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Another Beautiful Day, 2015. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Another Beautiful Day, 2015. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Heartbeats Accelerating, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 2.13 x 1.52 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Heartbeats Accelerating, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 2.13 x 1.52 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Self Portrait on a Gift Card, 2015. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Self Portrait on a Gift Card, 2015. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, The cool breeze off her back is my facecream, 2016. Collaged canvas and acrylic, 1.82 x 1.52 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, The cool breeze off her back is my facecream, 2016. Collaged canvas and acrylic, 1.82 x 1.52 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Black and White Bitch Painting a Butterfly, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 1.52 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Black and White Bitch Painting a Butterfly, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, 1.52 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Titled, 2016. Collaged canvas and acrylic, 1.52 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.

Sojourner Truth Parsons, Titled, 2016. Collaged canvas and acrylic, 1.52 x 1.21 m. Courtesy Tomorrow Gallery, New York.