1. The Biennale de Montréal 2014

It’s a bit unfair to condense Montreal’s year in contemporary art to a Top 3 in the same year that saw the relaunch of the Biennale de Montréal, now based at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and amalgamated with that institution’s previous Québec Triennial. With 50 artists and collectives on the roster, the biennial monopolized the fall season not just through its scale, promotional apparatus and an expansive (if sometimes awkwardly scheduled) slate of lectures, conferences, performances and screenings, but also by literally taking over the space of numerous satellite venues (both commercial and non-profit) like Vox, SBC, Parisian Laundry and Arsenal, among others. Of course, none of this would matter if the event wasn’t actually good—and, indeed, in the lead-up, it seemed the odds were stacked against the organizers, who were faced with a short deadline after the hasty merger between two institutions.

It’s all the more impressive, then, that director Sylvie Fortin and her two teams of curators (two each from the existing biennial and the MAC) managed to assemble such a thematically cohesive exhibit on a theme as broad as “Looking Forward.” The collective view of the future they presented was bleak but urgent, characterized by looming ecological disaster, the accelerated digitization and surveillance of social life, and the growing power of technological and financial capitalism.

One hopeful sign of things to come is that emerging Canadian and Quebec-based artists aren’t overshadowed by higher-profile international figures like Thomas Hirschhorn and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster—though my personal favourite work was Hito Steyerl’s video installation Liquidity Inc. (2014). Nevertheless, many young Canadian talents were highlights: Jacqueline Hoang Nguyen, Richard Ibghy & Marilou Lemmens and Althea Thauberger all showed particularly great work. Across the board, the standard was very high.

2. Jon Rafman at Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran, Montreal

A few years ago, when “post-Internet” was still a fringe category mostly debated on blogs and not yet a hot buzzword driving the cutting edge of speculative collecting, Jon Rafman’s art mainly lived online or in photographic C-prints of imagery culled from the web, like the pictures he appropriated from Google Street View for his celebrated, ongoing 9-Eyes project (probably still the work for which he is best known).

As his profile has risen, however, Rafman’s output has grown darker, more sensational and more opulent. It would be easy to say that Rafman was simply cashing in if his new work wasn’t so viscerally effective. His recent solo show in Montreal included a series of figurative sculptures called Manifolds (2014), extrapolated from his earlier series of CGI-rendered busts, New Age Demanded (ongoing). Instead of JPEGs or C-prints of digital renderings, however, the Manifolds are biomorphically abstracted, full-body figures 3-D printed in resin, gold leaf and concrete, and their relation to the Modernist figuration of Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti seems less ironic and more ambitious than before, even as their de-featured bodies warp and distort like futuristic anime monsters. To quote a fragment of the Ezra Pound poem from which New Age Demanded adapted its title, Rafman gives form to the “accelerated grimace” of the contemporary moment, which is often unsettling to behold.

Also in the show was Rafman’s video Mainsqueeze (2014), a schizophrenic mash-up of net-subculture detritus with art-historical images of depravity. As Rafman recently wrote in Artforum, he wants to capture “the general sense of entrapment and isolation felt by many as social and political life becomes increasingly abstracted and experience dematerialized.” This small show mainly felt like a preview for Rafman’s forthcoming 2015 solo exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, which is sure to be provocative.

Rafman is one of the very few Canadian artists in recent memory to have achieved international notoriety and influence so early in his career. What he will do with this position remains to be seen.

3. Julie Favreau’s Banner Year

In the spring of this year, Julie Favreau marked the end of her Bronfman Fellowship with a solo show at Concordia University’s FOFA Gallery (full disclosure: I wrote one of the catalogue essays). This month, at the Gala des arts visuels, she went home with the Prix Pierre-Ayot for best emerging artist in the city, along with a second nod—the prize for Best Emerging Curator went to Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre for a group show that included Favreau, Jacynthe Carrier and Vicky Sabourin.

None of these honours are incidental. As suggested by the “Videozoom. Between-the-Images” exhibition organized by Galerie de l’UQAM and shown at Western University’s McIntosh Gallery this fall, video may have overtaken abstract painting within the Francophone-Quebec art milieu (itself represented by the interminable “A Matter of Abstraction” retrospective at the MAC, which finally closed this September after a two-year run) as the dominant medium.

For Favreau, however, video is only one aspect of a singularly multifarious practice that enfolds sculpture, choreography, performance and installation. Though her work crystallizes in highly cinematic images, the magic-realist scenarios she stages defy reduction or definition. While representative of the ongoing influence of formalism and the current vogue for video in Quebec, Favreau stands above and apart from both. Her next challenge will be to expand her profile outside her home province.

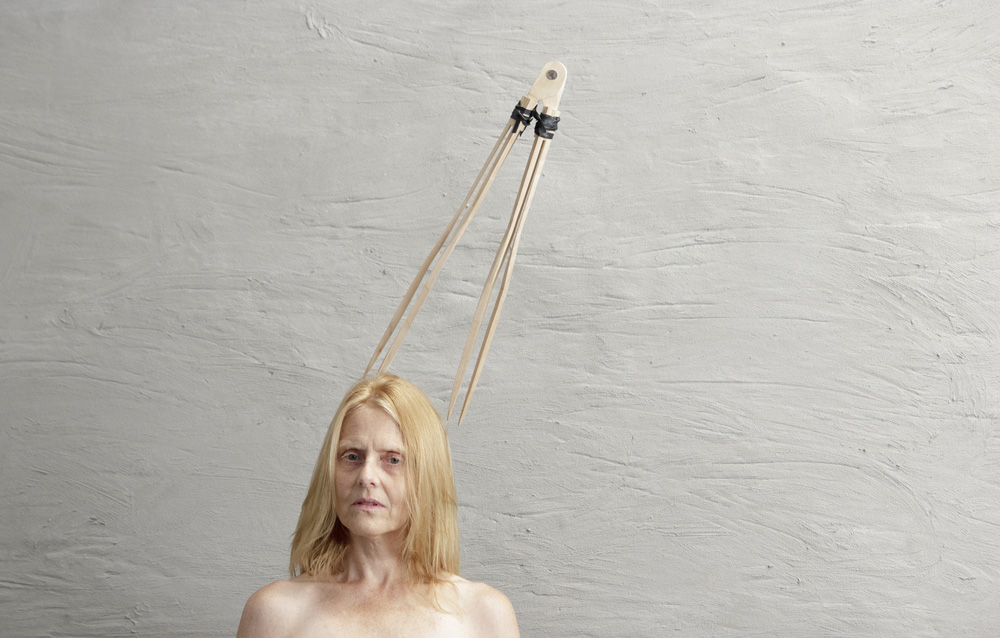

A film still from a work by Julie Favreau, winner of the Prix Pierre-Ayot for emerging Montreal artists.

A film still from a work by Julie Favreau, winner of the Prix Pierre-Ayot for emerging Montreal artists.