This is an article from the Summer 2015 issue of Canadian Art.

Two of the funniest, smartest guys in Winnipeg meet every Wednesday inside a tall blue house off Corydon Avenue, one of the city’s mainest drags, at around 8:30 p.m. Neil Farber sits on one side of the dining-room table and Michael Dumontier works opposite, and they listen to records, drink a few beers and paint, but mostly they talk about what they’ve painted. “Why is this little monkey so sad? What’s that guy up to? Why is he pouring his tea on the ground?” Each image wants a raison d’être and they’ve become uniquely skilled at plucking that from the cosmos. When they’ve hit on the solution—and that conversation might last hours, weeks, years even—Farber scrawls it on the panel. The painting is finished. Though the clubhouse has moved a few times and, quite famously, other collaborators have come and gone, they’ve convened in more or less this fashion for nearly 20 years.

I arrived at Farber’s house on a Tuesday afternoon, a day and some hours before their regular get-together. Farber answered the door and led me through the front room, past a shelf jammed like a Scrabble rack with six-by-six-inch hardboard panels awaiting their finishing marks, then past the dining-room workstation and down a few steps into the living room. Farber, Dumontier and I each took separate couches between the shelves of paperbacks and movies built against one wall, and a room-length unit filled with LPs lining the other. There had to have been a thousand of each. “What would you like to listen to?” Farber asked. For him, it was simple housekeeping or maybe a small gesture to make me comfortable; looking back, it’s a sign, pedestrian though it may be, that I’d been shown into their world. If their collaboration is also a document of their long friendship, as I’d come to think, work or play, you can be sure there’s a record spinning in the background.

The Royal Art Lodge got together in 1996, while its members were at art school at the University of Manitoba. They rose to prominence with the same ’90s drawing movement that sainted idiosyncratic doodlers like David Shrigley and Raymond Pettibon, and then disbanded in 2008. At its largest, there were six members, and at its leanest, three. Farber and Dumontier, both 40, were there from the first meeting to the final show. Along the way, they scored successful solo careers. Farber’s own practice weighs towards Surrealist painting while Dumontier is interested in formal Minimalism. Both are exhibited and collected widely. But they’ve also continued to honour the Wednesday tradition, maintaining an insanely prolific collaborative practice that’s resulted in international shows, books with titles like Constructive Abandonment or Animals with Sharpies and a body of work that handily outnumbers the vinyl records in Farber’s impressive collection.

In June 2014, the last year they’d be eligible, Farber and Dumontier were shortlisted as a team for the Sobey Art Award, held conveniently that go-round in their hometown. They didn’t win. But the show spurred the pair to produce their most ambitious work yet: Library 4—an iteration of an ongoing series. Two decades into their collaboration and it’s this latest direction, they reckon, that best gets at what they’ve been chasing all along.

In Farber’s dining-room studio, he explained that their method owes more to drawing and collage than painting. They cover the panel in tape and cut away the shapes of their subject—a mummy, a casket, a crevasse—so that when they apply their preferred pigment (often FolkArt acrylic craft paint), the edge is masked hard and the figure looks like it was pasted onto the board. It’s a technique Dumontier developed. The paintings happen quickly to help realize an idea before it grows stale. Farber isn’t big on brushes, so when the situation allows, he squeegees on colour with a playing card.

“In the paintings, it’s all about being simple and illustrative,” Farber told me, “so it gets out of the way of the idea. The main thing,” he explained, “is that you don’t think too much about how the mouse was painted, you just wonder why he’s playing a guitar.”

The act of painting excites them less and less. They much prefer the problem solving, the writing bit. “Paint a thing. Add something to it. Figure out why those two things are together,” Dumontier said. An image of a table flipped up against a wall is resolved by a small arrow pointing to its hidden underside and the words: “known location of illicit activity.” Another panel pictures a slapdash gallows and says, “Do it yourself.” Effectively, they’re trying to reverse-engineer jokes. If they spend an hour painting, they might spend four trying to crack the puzzles they’ve created.

“It’s becoming that more than half the paintings never get finished,” Farber said. There’s stuff that’s been started and sits around for years. Piles of unfinished work occupy a corner of the front room. Farber brought over a hardboard square painted with an image of a knife strapped to the end of a ruler. “A homemade bayonet,” Dumontier offered. Another good idea that had yet to get its masterstroke. Written on the reverse and on pieces of tape stuck to the front were possible solutions: “Stabbings per metre,” “Measuring your comfort,” “Far Enough.” The way they cook a punchline into its most economical, high-impact form is a triumph of restrictive poetry. They own the book The Synonym Finder by J.I. Rodale in triplicate, they told me. They call it their bible.

The panel reminded me of that old chestnut, “Measure twice, cut once.” “That’s not bad,” said Dumontier. Sometimes a plain description works best. Farber recalled a painting of a severed head that they simply captioned “head.”

Their earliest influences include Steve Martin, George Burns and SCTV, which tidily explains their proclivity for high-concept sketches, incongruity and absurdism. Farber described seeing a CBC segment on Dalí when he was young, and falling in love with the language of Surrealism. “The idea of painting a dream world still appeals to me greatly,” he said. “Why would you want to stay in the real world when you can use your imagination instead? And why just dreams? Why not nightmares?”

It is no coincidence that André Breton, the founder of the Surrealist movement, coined the term “black humour.” “There is nothing,” Breton quotes from Pierre Piobb in his book on the matter, “that intelligent humor cannot resolve in gales of laughter, not even the void.” Turns out, Breton and Steve Martin’s A Wild and Crazy Guy weren’t so far removed—Farber and Dumontier’s output establishes that connection.

Winnipeggers have a special relationship to the absurd, Wayne Baerwaldt, former director of Plug In ICA, who co-curated an extensive Royal Art Lodge touring show, “Ask the Dust,” in 2003, later told me by phone. “It’s sort of a place that’s been on hold since the opening of the Panama Canal.”

In their paintings, the pair summons that absurdity slivers at a time. Their images offer just a tantalizing little piece of the story. You’re left to “imagine all around it,” Farber said. Lately, it’s that writerly sense of narrative with an increased focus on language and voice that excites them most. The images are still important, but mostly functional now, he explained. “We are more interested in their minds than their bodies.”

The Typing (2011–) series changed everything, according to Farber. Dumontier painted two iterations: one, an old man seated at his typewriter in the bottom-right corner of the image with a blank page overtop, and the other, a young woman at her desk, pictured from behind in the lower-left corner. The work is reproduced as a digital print, and run through their grey DeVille—which Dumontier is mostly certain he got at a yard sale—now stationed in Farber’s dining room. A stack of each iteration lies out like printer paper. They zip the prints through the typewriter, and clack out messages from the desk of their characters.

In edition 276, for example, the man writes: “Not that I want to get divorced, but I think we could have a very nice divorce. We could sell the house and split the money. You would take your stuff. I would take mine. You would take the kids. I think we could have it sorted out in an afternoon.” In 459, the girl writes: “Nobody gets me. I am not a present.” It’s an elegant framing device that bypasses that waiting-for-eureka! part of their image-making practice and cuts straight to the payout. The characters are ciphers to be coloured by our imagination. They are, literally, blank pages to be inscribed.

At first, the pair split the typing duties, but as the series continued, Dumontier turned the keyboard mostly to Farber, “the best and funniest writer,” he said. With each communiqué, the characters grew rounder, voices emerged. The man is world-beaten. The girl is given to fits of bottomless nihilism and, in equal measure, earnest declarations of joy. Farber doesn’t imagine she’s the sort who keeps her apartment very tidy. Typing has become a powerful vehicle for generating ideas, many to be recycled elsewhere in their practice. So far, the series spans more than 600 one-off, hand-typed editions available through Toronto-based publisher Paul and Wendy Projects.

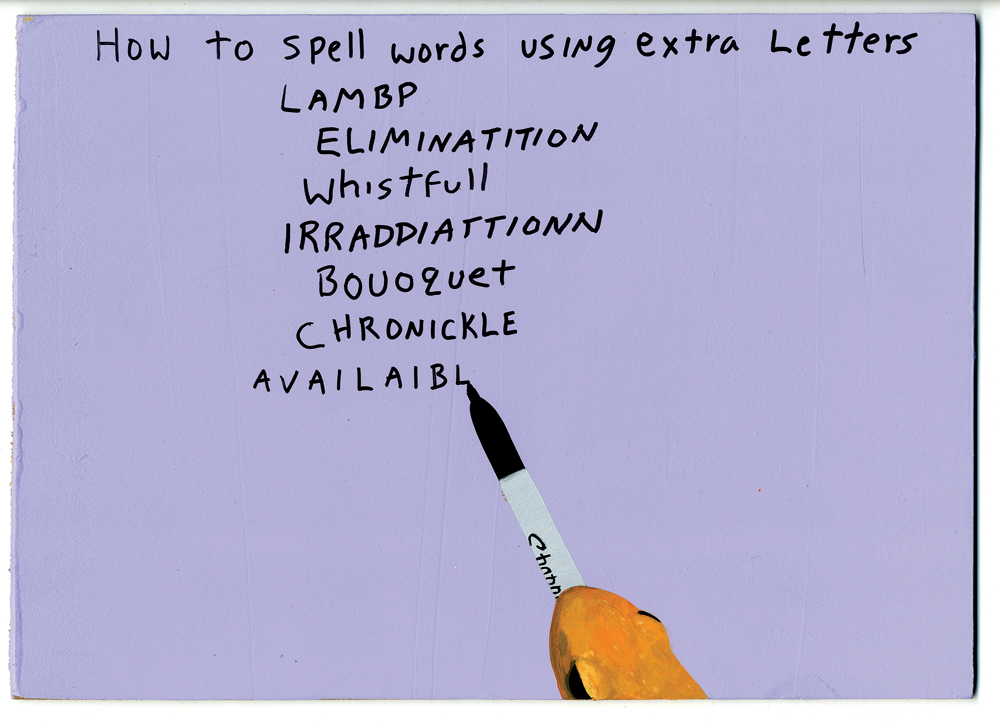

Displayed opposite 48 of their favourite such Typing prints at the Sobey Art Award shortlist exhibition, Library is the other project that defines their current artmaking. Each panel is painted with a crude book on a coloured background. The cover and, occasionally, the spine play site to an unlikely book title: “Blow Your Own Horn for Once,” or “Shittiest People in the World: Volume 1” or “How to Tell Your Grandparents Apart,” to name just a few. Sometimes, they’re accompanied by a quick image. All tiles are either two-, three- or six-inches square. Like Typing, the idea is simple and generative—another formula to wire directly into the punchline. Farber drafts possible titles on his iPad; he has hundreds backlogged and deletes them as they’re “printed.” “Today’s,” he listed: “Hot Bedding,” “Punished for Nothing,” “How to Balance a Person on Your Head.” Just like a real-life library, it isn’t any one title that makes the collection powerful, but rather the size and the scope of its total holdings.

When the shortlist was announced, Farber and Dumontier decided to make, from scratch, over just a few months, the largest installation of Library to date: 2,104 paintings of books, each panel tediously cut on Dumontier’s own table saw—a testament to their hardcore DIY ethic—and arranged on the wall with magnets into a 6-by-20-foot bookcase-shaped block.

Former assistant curator of the Sobey Art Award, Stefan Hancherow, told me he spent at least 20 hours with the piece over the course of the Winnipeg Art Gallery exhibit and he doesn’t even think he got through half of the titles. Hancherow called the installation “all-encompassing” and “overwhelming.” The series: “expansive” and “unending.” They’ve been following this idea for six years. It is a longterm accumulation. “It’ll always be there,” Hancherow said, “which is kind of a beautiful way to think of their practice.”

You can’t help but wonder how their own collecting habits, evidenced around the room—LPs, toys, musical instruments—affect their art’s core interest in typologies, bestiaries and otherwise organizing multiplicities. Farber handed me a tiny, watermelon-headed ceramic figurine; the archetype for his character design, he said. (To find them, search “anthropomorphic salt shakers” in Google, he later added.) Upstairs, he showed off his girlfriend Krista Gowenlock’s impressive toy room. Gowenlock has amassed one of the finest, most exhaustive collections of Jem and the Holograms merchandise in the country—maybe the continent.

While playing me choice cuts from the Fall and the Go-Betweens at his house the next morning, Dumontier guided me through his collection of illustrated children’s books, of books on outsider artists, of books on early art education, of books by midcentury Italian industrial designers. He has a leather-bound omnibus compiling every issue of a periodical called American Pigeon Journal that was published in 1979, because of course you couldn’t leave something like that behind.

“I think it’s pretty obvious we are collector types,” Farber said. “That’s a big part of what I do. Lots of characters, like a toy collection. Things separated and organized. Grids of similar paintings. I think it’s deep enough to be fundamental to our aesthetic.”

‘There’s an obsessiveness,” Dumontier told me, “I’m sure that’s part of it. It’s satisfying to see piles of things. But, like collecting, the Library never quite seems large enough. You get that rare record and you still feel empty.”

At their new studio, above a tattoo shop, just a few blocks from Dumontier’s house, he had the walls dotted with experiments from the “Shape Notes” show he presented at MKG127 in Toronto in January 2015; crooked nails wriggled out from one wall and, hanging nearby, a wooden mock-up of a trompe l’oeil doorway made from metal and string fooled my eyes more than just once. He’d built Farber some shelves in the back room to store a few of the 51 globe-headed mannequins, Farber’s latest project as well as his first foray into sculpture, that he debuted that week at the Winnipeg New Music Festival. There is Royal Art Lodge memorabilia salvaged from the group’s fabled studio on Bannatyne Avenue all over: mounted game heads, the suitcases still brimming with papers used to sort work by quality, bins of cassettes and CDs and videos, documenting hours of performance. They dug out a drawing from the very first meeting. These two have become the keepers of that history.

From another box, Dumontier unwrapped a multi-panel painting called Hospital Island (2001)—a horizontal water scene that imagines visitors arriving by boat to a pretty impractical medical facility. The pair collaborated on the piece during their Royal Art Lodge days sometime before Baerwaldt’s “Ask the Dust” show. More than 10 years early, it hints at so much of what’s important to their aesthetic today: hardboard tiles, composites, empty space. There it was—a landmark in their practice, living in a Rubbermaid.

Winnipeg artist and curator Paul Butler said he had to convince Dumontier and Farber to let him nominate them for the Sobey. He wanted to celebrate them because, professionally, he’s always looked up to them, he said. Their work, in the Lodge and afterwards, not only gave his generation a sense of what an art practice could be, but also, in his view, vividly influenced subsequent waves of artists. He also wanted to recognize that collaboration is tough. “Like bands,” he said, “It’s rare to stay together so long.”

“Like a band”—it’s an analogy they’ve heard from the beginning. They debuted as the hot, young things that everyone thought would flameout fast. Twenty years on, they’re the veteran songwriting team with a back catalogue that is thousands of hits long and growing longer still each year.

Their collaboration has been so successful because they understand each other’s talents; they respect each other’s side of the stage. The imagistic part of their practice is Dumontier’s, Farber told me, and the voice is essentially Farber’s, Dumontier said. But it’s that sound only they can make together—their own peculiar, heartrending, frequently hilarious two-part routine—that compels them to play on.