Larissa Fassler’s artistic practice is about observing daily encounters in the city. She records them to ask what they reveal about our social relations. Her large-scale plan drawings and unmonumental sculptures map her experiences of underground pedestrian walkways and major transit hubs, such as Berlin’s Hallesches Tor (2005), Alexanderplatz (2006), Warschauer Straße (2008) and Kotti (2009–14), and Paris’s Les Halles (2011). A Canadian working in Berlin since 1999, Fassler has also tracked the public reimaginings of ruined states, documenting the juncture of the former Palast der Republik and the recently reconstructed Berliner Stadtschloss in Palace|Palace (2012) and Schlossplatz I–VI (2013), and the neglected corner of Kurfürstenstrasse and Potsdamer Strasse in EPICENTRE (2015). She started research for her most recent series of drawings, Gare du Nord (2015), during a 12-week residency in Paris at the Centre international des récollets in 2014. This residency followed other extended visits to historically complicated and politically contradictory sites across Europe, all of which resulted in works titled after their locations: Regent Street/Regent’s Park (Dickens thought it looked like a racetrack) (2009) in London, Place de l’Europe (2011) and Place de la Concorde (2013) in Paris and Taksim Square, June 9–May 31 (2015) in Istanbul.

In these urban matrices autonomous people are united only by their transient roles in the flow of capital. As Helene Furján writes about more extensively in a catalogue essay titled “Autonomous Worlds: The Works of Larissa Fassler,” they are what French anthropologist Marc Augé calls “non-places.” Yet Fassler uses a form of psychogeography—an analysis of how geographic environments shape behaviour in public space, used as a disruptive tactic by Guy Debord, the French Letterists and Situationist International (circa 1957–72)—to reveal the complexities of each site and its subjects. Unlike the Situationists before her, Fassler updates the practice of psychogeography to include intersectional analyses of gender, race and class in late capitalist society. Fassler cannot deny her own privilege, but she can and does replace the male gaze of the flâneur and the blank stare of the frenetic commuter with the lingering presence of her body, with which she surveys each site. She maps different aspects of each site every day by walking its edges and counting her steps. Similarly, she demarcates each site’s most and least traversed routes, its interior spaces and its exterior perimeters. At times, she uses the somewhat absurd and irrational dérive (drifting) and détournement (rerouting) techniques to penetrate the seeming rationality of modern man and his city. As she walks, her body (petite, female) displaces the Vitruvian man, the modern measure of all things, to reinterpret—according to her unique corporeal experience—inhabited, material sites in the modern city and, by extension, to measure civil society.

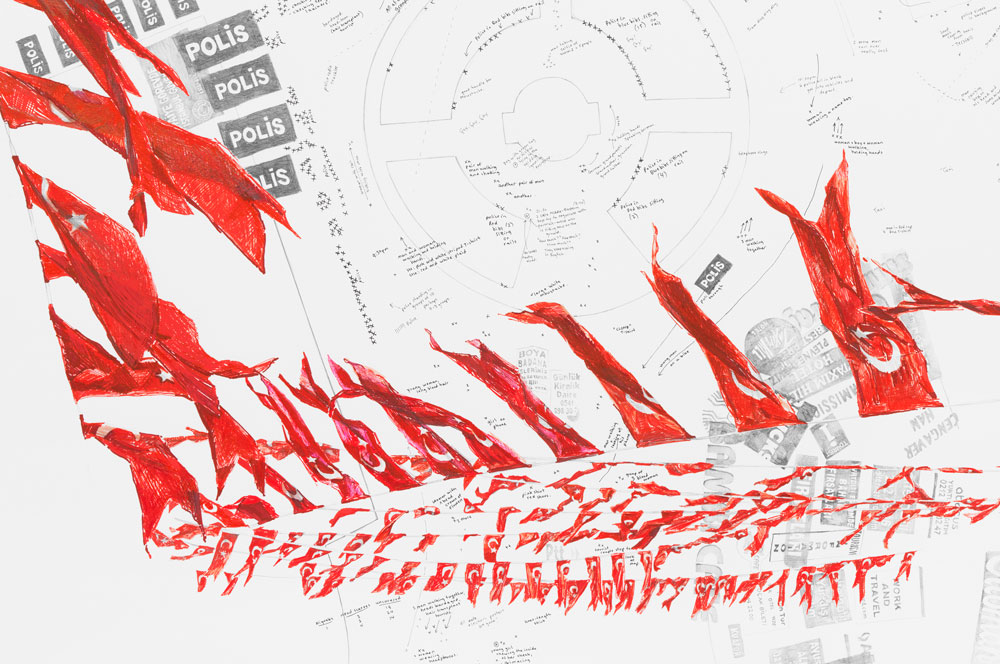

Larissa Fassler, Schlossplatz III (detail), 2013. Pen, pencil and pencil crayon on paper, 1.2 x 1.4 m. Courtesy Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

Larissa Fassler, Schlossplatz III (detail), 2013. Pen, pencil and pencil crayon on paper, 1.2 x 1.4 m. Courtesy Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

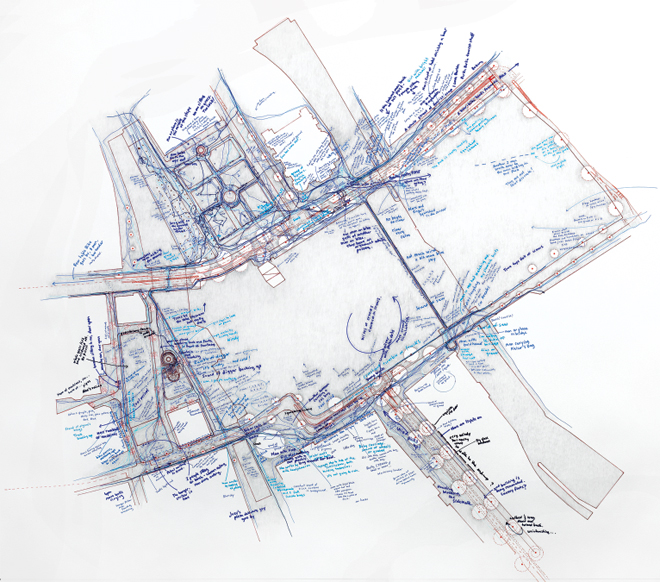

She draws her experience of these sites using a range of modified representational techniques from architecture. Her large, coloured-pen-and-pencil cartographic drawings use omnipresent plan views. They are spatial abstractions. In one of her earlier works, Warschauer Straße, architecturally rendered cutaways and cross-sections of the site frame the plan view of this U-Bahn/S-Bahn station. She uses conflicting perspectives and scales to unsettle the artist’s and viewer’s positions, and to flip subject-object relations. An artist-ethnographer of the everyday, Fassler most often observes the site from the point of view of her subject. This is quite literally the case in Schlossplatz Research V (2013) as she criss-crosses the plan view of Berlin’s Palace Square with sharp red-ink lines that map the trajectory of views from tourists’ cameras. In order to understand the drawing as more than an abstract representation, a viewer must imagine herself in the place of the tourists. Such discordant views are consistent in Fassler’s oeuvre. She uses them to fragment the omnipresent spectacle of the site, its media and its commerce, and to reveal its multiple subjectivities.

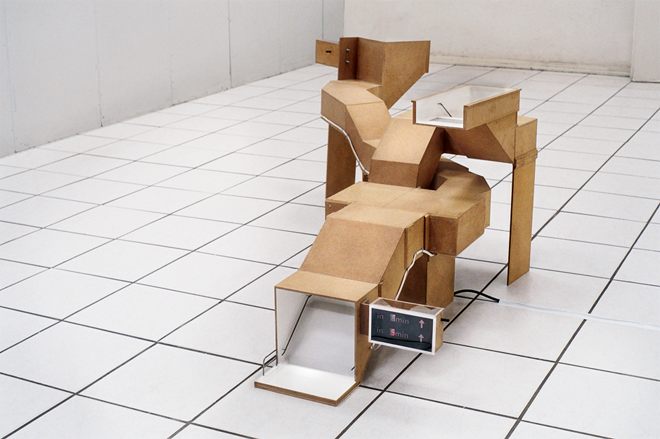

For many sites, Fassler also produces three-dimensional objects that exist somewhere between models and sculptures. In Hallesches Tor and Alexanderplatz, for example, the negative space of the pedestrian underground tunnels is rendered in positive form: absence is rendered present. These sculptures are models for the viewer’s imaginary projection, which is encouraged in some cases by audio tracks of buskers and footsteps. In Les Halles and Les Halles (tricolore) (both 2011), Fassler uses bricolage fragments to replicate the Forum des Halles, a shopping complex built in 1979 and demolished in 2011. In these works, and the room-scale Palace|Palace, the negative space of these abstract models of non-places has been completely filled in and viewers are confronted with the material realities of sculpture.

Fassler further challenges Augé’s idea of the non-place by recording the specific economic and social relations produced by each site. She gleans vast amounts of data, big data, about each site, including details about its users. Her data-collecting process is obsessive and subjective, and even she admits it can be comical or absurd at times. Visual data sets vary according to site, but include, among other things, official signs, posters, graffiti, advertisements and political messages. Again in Warschauer Straße, these types of representational imagery begin as photographs that the artist then draws, scans and digitally collages into her maps. These miniature hyperreal representations, flattened from varied perspectives, are included all over the surface of the drawing. They are signs, lifted from an imagistic world to be translated by the artist’s hand. Together they create a legend to decode the specific cultural language, including the work itself, particular to a place in time.

Larissa Fassler, Hallesches Tor, 2005. Wood, metal, digital clock sand sound, 60 cm x 110 cm x 2 m. Courtesy Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris.

Larissa Fassler, Hallesches Tor, 2005. Wood, metal, digital clock sand sound, 60 cm x 110 cm x 2 m. Courtesy Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris.

Fassler denotes the scale of each site by counting her footsteps. This is a quantifiable type of data, but it is also completely unique and subjective, dependant on the particularities of the artist’s body at a specific moment. Onto other planes, Fassler transfers detailed on-site observations from her small notebook to approximate corresponding locations on the drawing to chart the movements of other people—encounters of all types, gestures and expressions. In Warschauer Straße, a blue arrow points to a place on a rendered sidewalk: “Punks (3) sitting on ground (no dogs).” Other reflections mingle with snippets of overheard conversations. In doing so, she reintroduces specific identities, including her own, into these usually homogenous and seemingly generic spaces through which most people just pass.

Fassler performs a type of spatial feminism through her work. Emerging from feminist geography, spatial feminism analyzes how dominant power relations, particularly gendered relations, are produced and reproduced spatially. Its practitioners ask how people of all genders can act as agents to reshape patriarchal space into more inclusive, equitable spaces. Fassler’s documentation of each site is an act of agency in which she engages the politics of each space through her actions. She records the limits of freedom. This is not without risk. In some cities, you can get arrested for sitting in one place for a long time, walking unusual or usual routes repeatedly, writing notes, recording audio or taking pictures. As such, these otherwise everyday activities become acts of resistance within heavily surveilled and privatized public spaces. Fassler pays keen attention to how these sites are controlled—and by whom. What she chooses to document reveals the omnipresent power of white patriarchy and its intricate interweaving with commerce. Each is interdependent on the other. Each excludes and isolates the Other.

Fassler’s drawings are microcosms that reflect her experience of inequity and control in broader society. Her most recent work increasingly focuses on highly contested public sites that have seen recent conflicts, be it the Gezi Park protests, uprisings against former French president Nicolas Sarkozy’s xenophobic policies against the Roma, or the Gare du Nord around the time of the Paris attacks in November 2015.

Fassler’s process of layering a series of interpretations (or translations) of the same site in the finished work creates a topography of the shifting politics of a place that emerges over time. Taksim Square, June 9–May 31 logs the movements and activities of people on one of Istanbul’s largest squares from when the results of a recent Turkish general election were announced to the anniversary of the Gezi Park protests. Between May 28 and June 15, 2013, thousands of people gathered in Gezi Park at the edge of Taksim Square to protest proposed urban development of the park, one of the few remaining green spaces in the district of Beyoğlu. The protests grew to become a symbol of resistance against the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and its increasingly authoritarian and religious policies, infringements on queer and Kurdish human rights and involvement in the Syrian Civil War. Riot police repeatedly dispersed these sit-ins and protest camps until protesters violently clashed with them in mid-June. Millions of people across Turkey protested in solidarity. Arrests were made. People were killed. Erdoğan dismissed the protests, but the park remains untouched.

Larissa Fassler, Schlossplatz VI, 2014. Pen and pencil on paper, 1.2 x 1.4 m. Courtesy Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

Larissa Fassler, Schlossplatz VI, 2014. Pen and pencil on paper, 1.2 x 1.4 m. Courtesy Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

The three versions of Taksim Square unfold time in reverse chronological order. These deceptively unassuming pencil drawings, framed by loosely freehanded fluttering red Turkish flags, reveal the current tenuous state of Turkey’s secular democracy and freedom. As she has done in earlier works, Fassler draws Taksim Square in plan view. Highly rendered masses of İstiklal street signs and election posters encroach on parts of the square. It is a monochromatic image of constraint and control. Handwritten text excerpts and sharp arrows draw out the daily activities of people in the square: tourists shopping, men selling roasted chestnuts and seeds, Turkish boys selling water, drugs being traded, Syrian kids begging for money. There are many more men than women. Saudi women wear niqabs and Turkish women are in headscarves, jeans and short skirts. Police units and tactical squads amass at the park entrance and edge the square. Undercover police survey the crowds. They wait.

A similar tension, but without the feeling of constraint, is palpable in Fassler’s latest series, Gare du Nord. The Gare du Nord is arguably the most famous of Paris’s six main train stations. Opened in 1864, it connects the centre of Paris to its northern suburbs and EU destinations in the UK, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. The northern arrondissements are home to many North and West African, Middle Eastern and Indian Parisians and have suffered increased surveillance and sieges since the Paris attacks. Perhaps in an attempt to capture the scale of inequity and oppression, these are Fassler’s largest works to date. These precisely rendered black-, blue- and red-ink plan drawings are on canvas and enveloped in monochromatic gradient fields of nicotine-stained colour, smudged ink and charcoal. Bright blue-and-gold patterned backgrounds overlay the picture plane to disrupt the architectural space in Gare du Nord IV and V. These colours and patterns recall colonial decorative motifs from African Dutch wax prints that adorn many Gare du Nord commuters. Additional violent incursions of safety-orange draw attention to zones with a heavy security presence. Dotted, angled lines track surveillance points of interest. Again, these new drawings reveal multiple attempts by the dominant culture to contain the messy, chaotic disquiet of this culturally diverse Parisian transit hub and the complex social relations within that reflect broader society.

This work was recently shown at Galerie Jérôme Poggi in Paris. Unlike any of Fassler’s previous exhibitions, “Worlds Inside” activates the gallery architecture by wallpapering its interior with somewhat degraded photographic images of the Gare du Nord. Drawings hang on a background of detailed portraits of female statues from the building’s facade. Fassler’s collage-installation and impressively scaled drawings combine to overload the gallery, to re-register it with the world outside. Here, two worlds collide, but remain autonomous. The Gare du Nord is a self-contained site and so is the gallery, but they speak to entirely different socio-economic realities. Fassler collages the sacred bourgeois surfaces of the white cube with the profanities of what lies just beyond it, the inequities, materiality and transience of the everyday. She resituates the body of the political viewing subject within the body of her work.

Diana Sherlock is an independent curator, writer and educator based in Calgary. A collaborative project between Larissa Fassler and Mirko Martin is currently on view through Germany’s Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt until September 9. Later this year, Fassler’s art will be featured in an exhibition at the Esker Foundation in Calgary.

This is an article from the Spring 2016 issue of Canadian Art. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your mailbox before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.