I moved to Whitehorse with my mother and brother when I was eight years old. After 10 years of military service, my mother, Sally Tisiga, felt the impulse to reunify with our Kaska Dene family and decided to attend Yukon College, where she received a bachelor’s degree in social work. She has since worked primarily with First Nations communities throughout the Yukon and across Canada, with a focus on advocating for the rights of children. Since she is a survivor of the Sixties Scoop—a parallel system to residential schools that forced First Nations children into foster care and adoption arrangements for the purpose of fracturing family and community—it is no wonder that she concentrated her passion on social justice, though as a youth I could not, at times, understand the endurance of her suffering and frustration. Nevertheless, I believe it was her persistence and resilience that laid the foundation of my worldview and subsequent engagements in art and social support.

For roughly the past decade, I have done community work in Whitehorse, which in many ways has paralleled my development as an artist. Starting in my early 20s, I worked as a residential-support and day-program worker for an NGO that assists people living with mental and physical disabilities. During that time, I was introduced to philosophies of support such as ableism and the person-centred approach, which are used to guide the attitude of care and facilitation needed to empower clients to live as fully and independently as possible. There was also enough flexibility in a shift to pursue some personal interests. I began making ballpoint-pen drawings, and although I had dabbled in painting prior, this casual distraction would play a significant role in my eventual art practice.

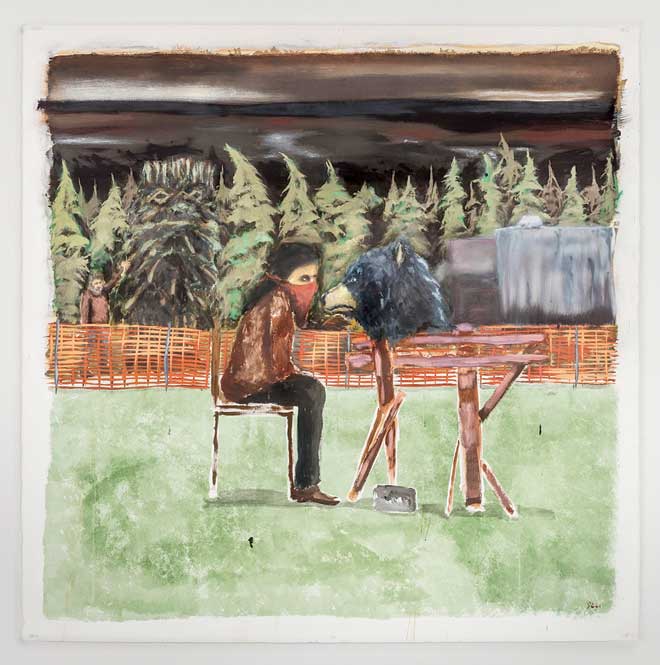

Joseph Tisiga, Fabricated Fear May Only Prolong Risk, 2016. Watercolour, acrylic and oil on paper, 1.31 x 1.31 m. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Joseph Tisiga, Fabricated Fear May Only Prolong Risk, 2016. Watercolour, acrylic and oil on paper, 1.31 x 1.31 m. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

For the past four years, I’ve worked for another Whitehorse-based NGO, the Skookum Jim Friendship Centre, first as a program support worker and now as manager of the program at the centre’s emergency youth shelter. The demographics of the youth shelter are predominately First Nations youth between 17 and 24 years old. These young people are largely fractured from their families and community. Many struggle with alcohol and/or drug use or addiction, have abandoned their high-school education and have lived lives heavily mitigated by our social systems. The philosophies of support that define my work are deeply tied to harm-reduction modalities, trauma awareness and non-biased neutrality.

I mention these philosophies as they are typically regarded to set the standard mentality and approach for those employed to provide service to vulnerable and marginalized people in the Yukon. These ideas of engagement can also be regarded as contemporary and evolving in contrast to attitudes of the recent past, in which the treatment of individuals could be viewed as paternalistic and punitive. Arguably, the actual impact of these services on people absorbed in the system has not changed, regardless of the altruistic intent to redress the principles of support. This isn’t totally surprising, as the system was and largely continues to be brokered by individuals and attitudes that apply status quo markers of stability and health—impossible realities for those marred by social policies intended to strip humanity and self-authority. The system, itself unhearing, unseeing and unfeeling, requires the worker to apply its spirit and intent through a filtering mechanism intrinsically bound to the structural limits of their position and departmental authority.

This systemic dysfunction can play out in numerous ways, but the end result is regularly an automated failure to meet the demands of complex personal and social barriers. Due to the disintegration of community or familial fabrics, individuals typically can’t rely on natural supports—a reality compounded by personal and intergenerational traumas that perpetuate conflict, violence, unhealthy coping and abandonment. Subsequently, a reliance on and absorption into the system, however broken and misdirected, becomes a necessary lifeline.

My awareness of this dichotomy was gradual. Its dystopic misalignment has been personally deflating. If there is a professional silver lining, it has been working with grassroots organizations like the Skookum Jim Friendship Centre, where I have learned to reframe my engagement as short-term, pragmatic, day-to-day support to ease some strain of burden on clients. The experience has also instilled in my mind a deep sense of contemporary mythic conflict, one that pits the subdued realities of a complex human narrative against the ethereal spectre of…what? I don’t think using a term like colonial structure would accurately describe the antagonistic counterpoint to this conflict. But whatever it is, it is distinctly alive and non-human.

I have come to think about this ineffable conflict as a kind of supernatural banality. To address these issues in practical, concrete ways is challenging, and I have often felt that I lack the language to articulate the nuance of these magical situations. It can often feel like the only role left to occupy is as an ineffectual witness. Responding to this sensation of being a hapless bystander has become the impetus for my artistic development. It is the impulse to speak into or talk back to conditions of reality where there is no single or identifiable person or cause to hold accountable. Orienting these issues in a mythological context, at least for personal reference, struck me as pragmatic and vast. I refer to this as Indian Brand Corporation, or IBC, which originated in my art practice in 2009 and, not so inexplicably, stuck. IBC has become a central nervous system for me to make work that hinges on the vague and corruptible histories that inform my identity, but are also oriented by the same supernatural ability that allows Dzohdié’ to kill a Giant Worm or Wile E. Coyote to paint a workable tunnel on a canyon wall.

Joseph Tisiga, An Exercise in Solidarity, 2016. Watercolour on paper, 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Image courtesy Diaz Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Joseph Tisiga, An Exercise in Solidarity, 2016. Watercolour on paper, 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Image courtesy Diaz Contemporary. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The gradual construction of a personal language and landscape in my art practice has generated a quality of agency I felt was lacking in my professional engagement. More importantly, it met an ancestral hunger for mythic orientation. Growing up remotely from my Kaska Dene community, immersed in the beige confluence of Western culture, I felt I could not be authentic in my cultural relationship. Yet nothing could be more singularly authentic than an inconsequential mythological construct to provide order for the mind of a cultural amnesiac. Though I cede to default tendencies like painting, I have generally felt ambivalent about artistic mediums or aesthetics. I am motivated more by acting in a role of self-agency, by whatever means available. This is for no better reason than to contribute something accessible to the drone of cultural dialogue—something that might resonate and prompt a viewer to consider, dissent and speak back.

The privilege of participating in an artistic dialogue is something that I’ve carefully considered over time. For me, it is an attitude that results from the stigma of art being a pious act, perpetuated by interests that are insular, self-referential and reaffirming. These interests, like those of the individuals who work to unwittingly broker the deployment of social support, seem to me to be anchored in profane and ambivalent regard for the very vulnerable and human necessities that—for better or worse—ultimately depend on its structure.

This article appears in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your mailbox before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

The Skookum Jim Friendship Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon, February 2017. Photo: Joseph Tisiga.

The Skookum Jim Friendship Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon, February 2017. Photo: Joseph Tisiga.