Janice Wright Cheney’s widows (Widow and Widow Walking, both 2012) are life-sized bears armoured nose to paw in felted woollen roses and smooth velvet hide. They are beautiful, but strangely so; they even seem aware of their strangeness, seem questioning—how did this come to be? It’s partly in their posture, in Widow Walking’s tentatively raised paw and in Widow especially, who stands up on her hind quarters as bears do to sniff the air, seeking the lay of the land, puzzled. She seems caught in an ongoing moment of self-bewilderment—an appropriate attitude for the grieving, for whom the balance of the whole world has shifted, making every day into a question.

The bears have a fairy-tale quality, connote Sleeping Beauty, hidden behind a wall of roses. But rather than pre-adolescents waiting to be woken and learn the ways of adult lovers, these are adults learning to live with the loss of their life partners. As widow-bears, they blur the line between human and animal as fairy tales so often do, brothers metamorphosing into swans, frogs into princes. Wright Cheney’s bears are implied to be living out a gendered grief, culturally ascribed, one that seems more human than animal—though on the other hand, grief is a wild emotion, one that may well turn us into some bearish version of ourselves.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow Walking, 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 114 cm x 229 cm x 79 cm. Collection of Telus Garden. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow Walking, 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 114 cm x 229 cm x 79 cm. Collection of Telus Garden. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

The obviously “made” character of Wright Cheney’s bears helps to blur the line between human and animal. The roses are clearly handicrafts, the kinds of things that are usually intended to decorate and delight, but affixed to the bears, they become paradoxical. The roses make the bears approachable even as—thanks to their bulk and claws—they remain profoundly other. The ever-so-tactile roses say approach; the claws say beware.

It is a paradox found elsewhere in Wright Cheney’s works—in Coy Wolves (2010), sculptures which reference the hybrid offspring of coyotes and wolves increasingly prevalent in New Brunswick. Wright Cheney dresses these quintessentially wild figures both in textile “pelts” and in the “furs” your grandmother may have worn. These textile-skinned, fur-adorned hybrids ask some of the same questions the widows do; they also bring human and wild animal unsettlingly together. But I remain particularly drawn to the bears, with their lush pelts of roses, because of what they do to my understanding of beauty, femininity and grief.

Janice Wright Cheney, Coy Wolves, 2010. Textile over taxidermy forms, found fur and accessories. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

Janice Wright Cheney, Coy Wolves, 2010. Textile over taxidermy forms, found fur and accessories. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

In the Western European imagination, the rose is the symbol of a certain kind of feminine beauty: diminutive, delicate, ethereal, fragile. The bear, on the other hand, is a hulking figure: muscled, clawed, feared, usually connoting the masculine rather than the feminine. Insofar as the bear has a feminine aspect, it is as the mother bear, fierce defender of her cubs.

What, then, of these widowed bears? They are not mother-figures, nor are they reducible to the delicacy of roses; they both encompass and exceed typical notions of femininity. They are strange. And this is part of what makes them feel so…real. For all that they are clearly “pretend” creatures, counterfactuals lumbering out from Wright Cheney’s imagination, they feel real in the sense that strangeness is so often confirmation of reality. It’s when I’m in the presence of a strange animal that the world feels most real to me, outstripping my mere ideas about what is real, leaving me with my mouth hanging open. It’s partly their size, partly their insistent tactility, but also partly the strangeness of these widows that convinces me, in the moment, of their realness.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow Walking (detail), 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 114 cm x 229 cm x 79 cm. Collection of Telus Garden. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow Walking (detail), 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 114 cm x 229 cm x 79 cm. Collection of Telus Garden. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

The beauty of a rose, even a fabric rose, is so familiar as to be a cliché, but married to hundreds of others and fastened to the massive form of a bear, it becomes odd. The rose’s beauty, otherwise taken for granted, is called into question—I’m not sure whether “beauty” is even the right word. It may depend on whether you conceive of beauty as something like Aquinas’s integrity, proportion and clarity, or a more Baconian beauty that requires a measure of “strangeness in the proportion.”

For if the widows make me think of Sleeping Beauty, they also appear as Beauty and the Beast peculiarly rolled into one. It’s a complicated beauty, the roses challenging how we see the bear musculature, the musculature challenging how we see the roses. How do these belong together? What kinds of beauty do they embody? I’ve always wondered how much strangeness could be accommodated by “the proportion” Bacon felt beauty required, and the bears bring that question to mind. Can there be too much strangeness; is there a critical mass after which beauty collapses into something else? And if there is such a line, how close are the bears to crossing it? They’re at least close enough to bring the question into view.

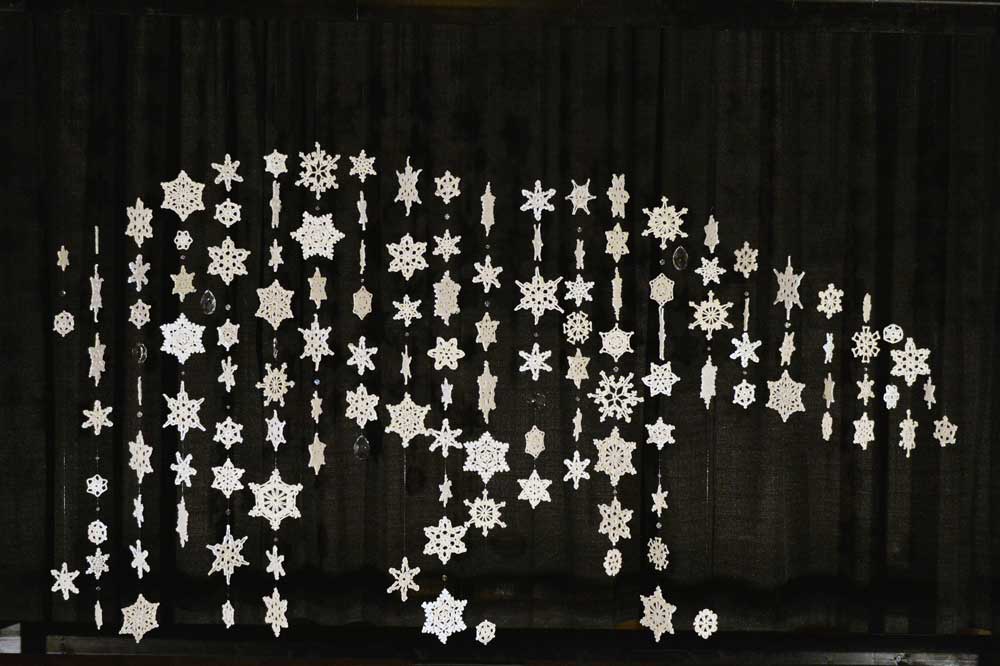

Janice Wright Cheney, Spectre, 2014. Crocheted wool, crystals, wooden armature, site specific installation at the Banff Park Museum. Photo: Sarah Fuller.

Janice Wright Cheney, Spectre, 2014. Crocheted wool, crystals, wooden armature, site specific installation at the Banff Park Museum. Photo: Sarah Fuller.

A similar complication emerges in Wright Cheney’s later work, Spectre (2014), which consists of rows of crystals and intricate crocheted snowflakes hung so as to create the shape of a polar bear, a shimmering curtain-bear. Like the widows, this bear is life-sized but composed of small and less inherently unsettling beauties. The polar bear, however, is decidedly ethereal, lacks the muscular quality of the widows, who are built on solid taxidermy forms. So the contrast between the ethereal and the substantial is less pronounced in this instance, and the apparition of the bear, though uncanny, may be less challenging to some of the more common understandings of beauty.

I remain curious about the roses and their relationship to beauty partly because they strike me, as I’ve said above, as a kind of armour. They’re costume-like, and around the bears’ faces the roses become a mask behind which the eyes peer out. I think of armour because of the name “widow,” which invites me to think of the bears as vulnerable, and the roses, for all their delicacy, then seem a protective covering. As armoured, the bears again challenge my ideas of what the feminine is or what it may accomplish. What might a feminine armour be, what might it do? In this instance, the bears’ armour is both something to hide behind and bold mark of the widows’ strange new bereaved selves, self-concealment and fierce display being the mixed message of many armours, masculine and feminine.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow, 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 239 cm x 91.5 cm x 76 cm. Collection of Glenbow Museum. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow, 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 239 cm x 91.5 cm x 76 cm. Collection of Glenbow Museum. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

The paradox presented by the rose-armour also seems characteristic of grief. The roses are a distraction, drawing attention away from the depths of the grieving body, but they also draw us toward it. They both beckon and conceal: Come close, but not too close. This is often how it is with grief over a great loss: we want sympathy but also want to be left alone; we do and don’t want to heal, do and don’t want emerge from grief. These bears, however, are indeed emerging from their grief.

Wright Cheney has said that she had Victorian traditions in mind when she was dying the fabrics for the roses: “Traditionally, following an extensive period of wearing just black, widows would then wear purple or violet during their stage of grief.” These widows in their reds and violets are past the crises of their grief. I imagine them in the disorienting stage of settling into a new normal, imagine Widow, Walking, paw raised, taking her first steps into a new equilibrium.

Sue Sinclair is a poet, a faculty member at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, and a poetry editor at Brick Books. Her latest book is Heaven’s Thieves, and her interests include aesthetics, theories of beauty, the intersection of literature and philosophy, ecopoetics and contemporary poetry.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow (detail), 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 239 cm x 91.5 cm x 76 cm. Collection of Glenbow Museum. Photo: Jeff Crawford.

Janice Wright Cheney, Widow (detail), 2012. Wool, cochineal dye, velvet, taxidermy form, pins and wood, 239 cm x 91.5 cm x 76 cm. Collection of Glenbow Museum. Photo: Jeff Crawford.