In preparation for his performance of Révérence at the upcoming 21st-annual Canadian Art Gala this fall, Brendan Fernandes was in Toronto to lead a rehearsal. To be performed throughout the night, Révérence will continue the artist’s recent incorporation of classical dance within his performance and installation practice. The New York–based artist of Kenyan, Indian and Canadian descent came to prominence through sculpture and installation works that question notions of authenticity, translation and labour. In recent years, Fernandes has returned to his training in dance—cut short by injury—appropriating aristocratic Western rituals into a postcolonial framework.

I met with Brendan prior to the rehearsal, where we discussed the origins of ballet in the court of Louis XIV, the classically trained body as a site of labour and the need for a queering of the canon of ballet.

Nicholas Brown: Your recent work has incorporated dancers and the body as a subject. Can you talk about this turn?

Brendan Fernandes: I have a history as a dancer and I was curious about this re-entry into the “footmade”—as opposed to the handmade—in art. A lot of my work deals with language: the loss of language, how language is translated and the lack of language. In the history of dance, we’ve lost many dances because we didn’t have a way to score.

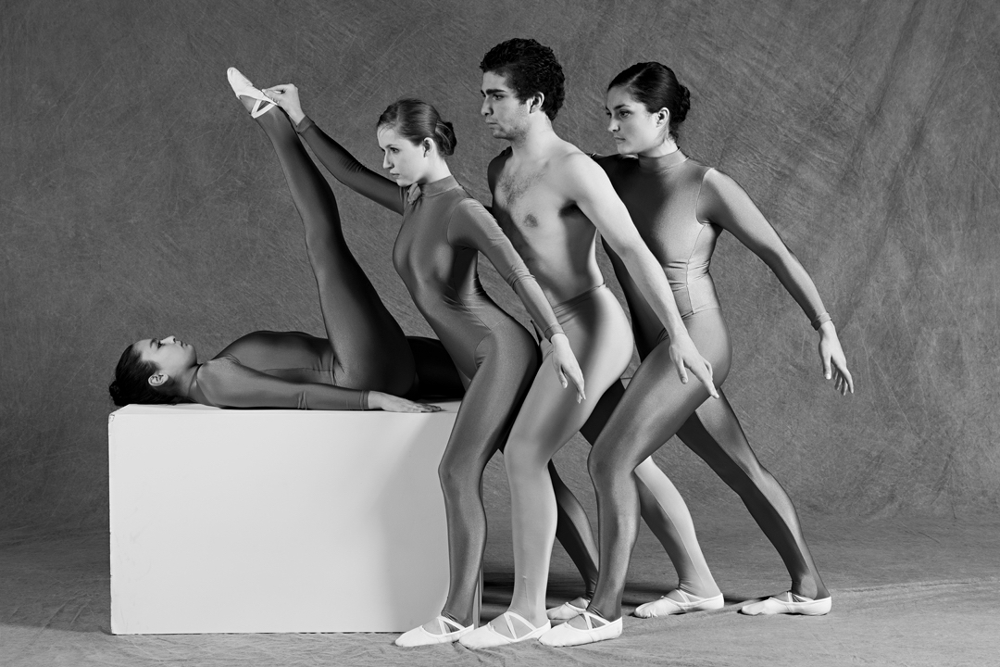

Brendan Fernandes, Inverted Pyramid (performance still), 2014. Dancer: Jenna Savella, soloist with the National Ballet of Canada. Courtesy Varley Art Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Brendan Fernandes, Inverted Pyramid (performance still), 2014. Dancer: Jenna Savella, soloist with the National Ballet of Canada. Courtesy Varley Art Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

NB: I’m interested in the role of the document, the archive and the score in relation to your object-based work, because there’s the stillness or the grounding of the object and at the same time there’s the ephemerality of movement.

BF: To me, stillness speaks to social and political questions relating to Marxism and labour. A lot of my work comes from the fact that I couldn’t dance anymore; I stopped dancing so I became stilled. And dance, specifically ballet, insists on a certain type of body. I question that, but also the labour involved in performing: we see virtuosic movement, and the theatre creates this apparatus to view the body from a distance, so the body becomes dehumanized. We see the body in strength and fortitude but we don’t necessarily question that as labour. It’s beautiful, it’s ephemeral, it’s romantic, and so the body gets dragged into those questions of being, in a way, othered.

NB: How does this figure into your use of dancers in spaces like the museum and gallery, where people are moving around them? This is a component of Révérence, the work you’re developing for Canadian Art’s Gala.

BF: Yes. When I present dancers in the museum and gallery space, this breaks the usual etiquette of the stage: you’re seeing the body sweat, you’re seeing the body breathe, make noises, express pain, you can smell the body. Part of that confrontation or discomfort is what I’m doing with Révérence. Révérence is a formality: at the end of class, the dancers bow to the teacher, they bow to each other. And with the bow, there’s a hierarchy, but you’re also giving your body to each other. Ballet started as a series of baroque gestures, as a way to bow in the court. Eventually Louis XIV formalized it to become an art form and other courts started to adopt it.

NB: In this case, the dancers will be bowing before a court of art patrons.

BF: Yes, they will perform bows to the members of court, in a certain way. This elite who attend the gala, a different performance space, are asked to participate.

NB: But not necessarily willingly!

BF: Exactly! The piece was originally commissioned for the Sculpture Center in New York, and I’m really excited to expand it for performance on home turf with Canadian dancers, and for the Canadian Art Foundation, who have always supported me. This idea of bodies in a promenade, all bowing as you enter the space, it’s confrontational. As we rehearse it, when I enter the room and they bow to me, it feels strange. These bodies are giving themselves to you, and it’s almost like falling. When you collapse the spine, there’s a sense of surrender, of vulnerability, a sense of giving up.

NB: It’s an interesting intervention in a time-based work because the bow signals completion, the moment where the dancer stops being the performer and goes back to being a human. But here you’re constantly cycling through it.

BF: A couple of years ago a number of principal dancers from American Ballet Theatre were retiring and they had these epic bows that lasted 30 minutes or even longer, and I was thinking, “What is happening to this dancer right now? Are they actually enjoying this moment?” And the idea that you have to keep labouring, and everyone is acknowledging and clapping and throwing flowers, but you have to keep on labouring. A strange conflation of expectations, which I think goes back to the idea of etiquette. Types of bows indicate your station: the deeper you bow, the lower you are on the class scale, the closer you are to the floor. Like your body has fallen on the floor. It made me think about this idea of queer otherness, and queering through the dance floor, of Orlando. Of bodies that were taken, and the gay nightclub is a sanctuary for many queers, and the idea that these bodies were taken, and they fell. These fallen bodies resonate with me.

Brendan Fernandes, Working Move, 2012. Digital prints. Photo: Michael Love.

Brendan Fernandes, Working Move, 2012. Digital prints. Photo: Michael Love.

NB: The frailty of the body as grounded in the relationship to the floor, to gravity.

BF: The floor is what we dance on and the floor hits back. It hurts your body, so when we dance there’s always the question, what’s the floor made out of? When I showed The Working Move (2012) at the Stedilijk Museum in Amsterdam, we had built a sprung floor in the entrance of the museum. It’s an endurance piece that uses the museum apparatus: plinths as devices of obstruction, of burden, but also as objects of rest. The day of the performance, the dancers said they wouldn’t perform because the floor was hitting their feet—even though it was raised, the concrete underneath was still penetrating. And so we had to find a solution, which was to buy them all special shoes and then alter the costumes. It was a very strong moment for me to be like, “Yes, dancers are giving themselves the right to speak, to give themselves power and agency.”

NB: In most of your work that involves dance, you are the director, the choreographer—you’re calling the shots. Has this relationship changed for you?

BF: It’s a relationship based on my insecurities of being a broken, older, former dancer. I won’t say ex-dancer, but former. It’s about putting my body back into my work. Earlier, I was always on the periphery, which is also very difficult because I wasn’t used to giving directions to dancers. And so for me that was a change, perhaps like the relationship between curating and being an artist. I’m always performing in a certain way, but not necessarily with the same sense of embodiment.

Brendan Fernandes, Standing Leg (performance still), 2014. Courtesy Kitchener Waterloo Art Gallery. Photo: Felix Chan.

Brendan Fernandes, Standing Leg (performance still), 2014. Courtesy Kitchener Waterloo Art Gallery. Photo: Felix Chan.

The only piece I’ve really ever danced in was a solo called Standing Leg (2014). When I was a dancer, my feet were always critiqued. I don’t have the proper, desired feet for ballet, so I would use a device to bind my feet to give me these arches—a foot stretcher. And so in the performance, I am bound to this object and I’m trying to stand up. The piece was choreographed with a score, where I’m conditioning and moving the body very slowly in a way to prepare it to stand up. And that is sort of like an antithesis to a solo. It’s like my still solo, my solo coming back into the dance world. “This is me.”

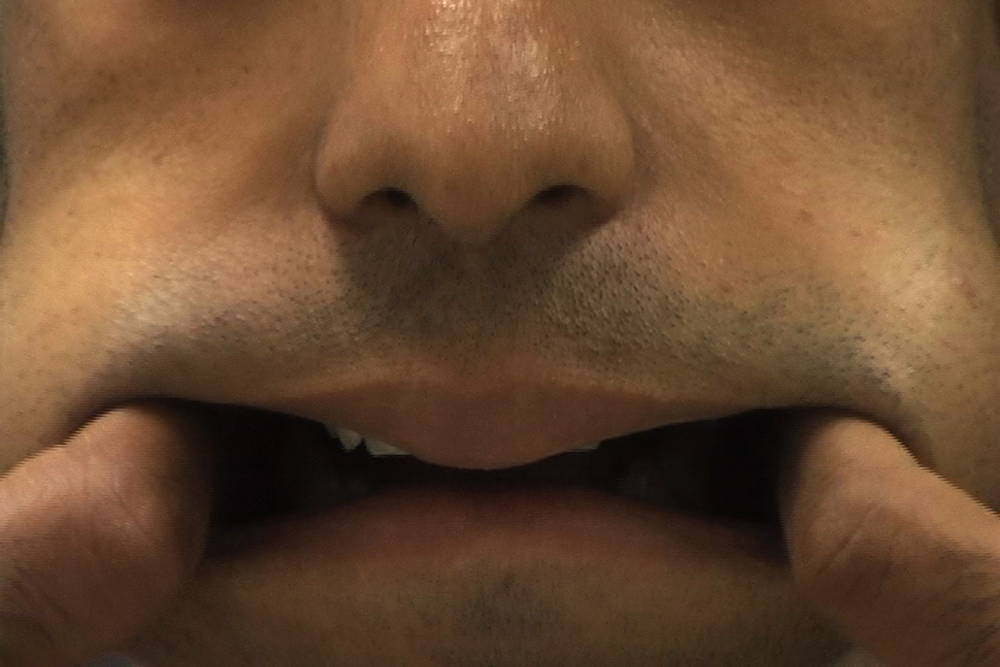

Brendan Fernandes, Foe (still), 2008.

Brendan Fernandes, Foe (still), 2008.

NB: This reminds me of Foe (2008), where you’re subjected to a different kind of physical conditioning and alteration.

BF: I hired an acting coach to teach me to speak in my cultural accent. It’s the question of authenticity: am I more myself if I speak in these voices? As I made this newer performance works I’ve been thinking about the ideas of how Foe was an endurance performance that I made with notions of blurring the body. She’s telling me, “Don’t move your jaw, let the tip of your tongue touch the top of your mouth.” It’s about choreographing the face, moving this way or that way to make the right sound. But in that isolation of not moving my top jaw to make it sound more like an Indian accent, I was isolating muscles I normally use when I speak, creating a pain in my jaw.

Brendan Fernandes, Night Shift (performance still), 2013. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Brendan Fernandes, Night Shift (performance still), 2013. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

NB: These works address the natural and the unnatural: the gait, the way that you walk and the speech patterns of speaking naturally, both of them can be so controlled and also can be used to make you completely uncomfortable in your own skin.

BF: Totally. You can spot a ballet dancer walking in public. But I also think about Yvonne Rainer and the idea of being pedestrian: pedestrian action and pedestrian movement is still very important to what we do in contemporary dance. We’re talking about everyday motions but there’s still an affect. In the piece Night Shift (2013), which I created for Nuit Blanche with Michael Trent and Dance Makers, one audience member said, “I was promised a dance but these dancers are just doing menial labour.” That was funny because, for me, it was about these gestures of shredding paper and moving across space, but the dancers had this trained-ness, they moved in a very affected way.

NB: Purpose and poise.

BF: I’ve been asked, “Why work with dancers? Why not work with everyday bodies?” But for me it’s about the dancer’s body, the trained body that will move in a specific way that is different from the everyday. That’s why I go back to ballet because it requires the most trained body, which has Western hegemony built into it. And I keep bringing up Misty Copeland, who was the first black, female principal at a major international company. The critique from ballet aficionados is her body is too “strong.” From a feminist viewpoint, she’s too powerful, and the power dynamic within that question, combined with her status as a woman of colour, goes straight to the canon of ballet.

NB: You’ve talked about the importance of scoring and notation. To what extent do you use those methodologies in your work and in the archiving of you work?

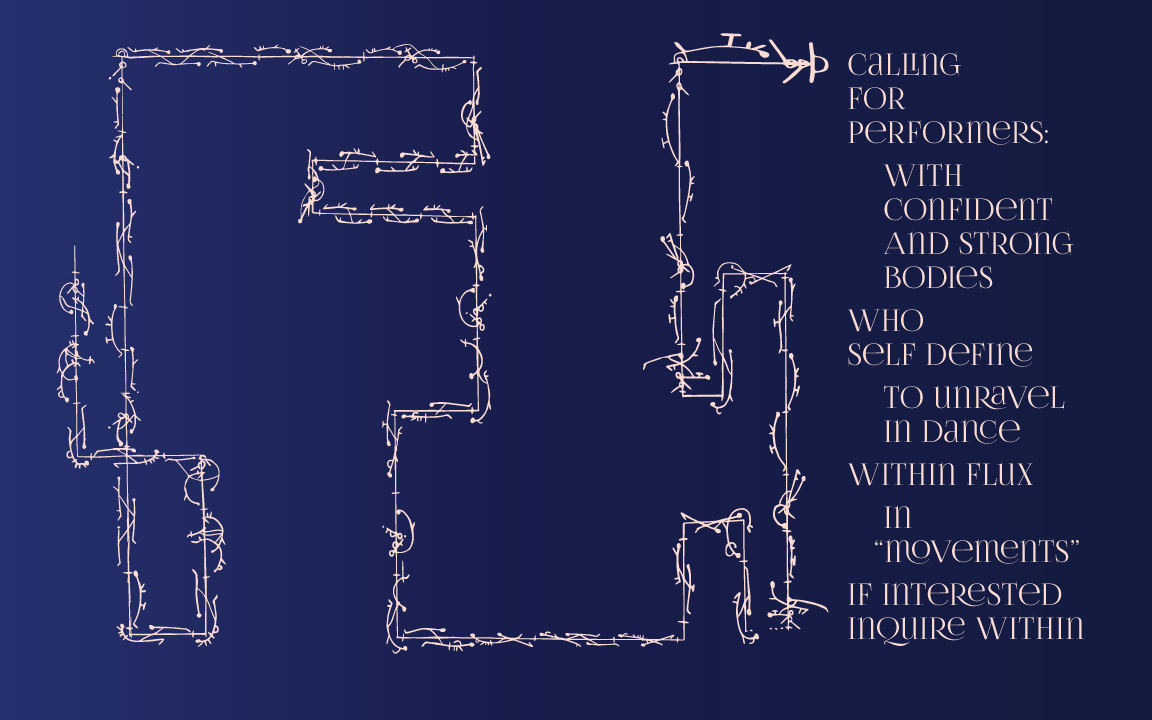

BF: I’m currently working on a piece where I’m looking at brushstrokes in historic paintings as hand motions, then using them to create scores. And I’m calling for bodies because so often the call for the body is so specific that it excludes a lot of people from being able to participate. A company recently asked me, “Who do you want…blonde, five feet, 100 pounds?” and I was like “I want dancers!” That was the thing that always made me uncomfortable within my own skin because, as a dancer, you’re giving your body, but it’s also being critiqued. So I’ve been writing these scores asking for queer bodies. One calls for strong and otherwise authoritative bodies to dance in flux in reaction to motions. And I’m putting these text pieces out into the world asking dancers to self-define and then within that we’ll all work together and interpret a score from these abstract patterns.

Brendan Fernandes, Minor Calls (in progress), posters and performance.

Brendan Fernandes, Minor Calls (in progress), posters and performance.

NB: I was fascinated to discover that, late in life, modern-dance pioneer Rudolf Laban created notation to increase efficiency for Fordist production, to eliminate so-called shadow movements. It seems salient to your practice that dance notation would be used to create a more efficient workforce.

BF: Definitely, that makes me think of Jonathan Crary’s book 24/7, the idea of how do we make the body work more efficiently. I go back to the handmade and the footmade. But also in the art world, the work that’s made by the hand is still what’s considered the most valuable. This makes me think about re-performance and the archive. Many dances in ballet history don’t exist anymore because we don’t have the archive, so now we’re using the camera as a device to archive it, but what does that mean? The challenge of a capitalist society makes us want to have everything commodified in some kind of way because the document becomes something of much value then. It’s a question of time and value.

Révérence will be performed continuously during the 21st-annual Canadian Art Gala on Thursday, September 22. Click here more info and to purchase tickets.