It can hold a single wall, even at its radically reduced size. Just 7 of the more than 70 photographs on view are the kinds of big pictures this famed German photographer is known for making. The others are small, hardly bigger than the colour plates in one of the books on his celebrated work. Rhine II, framed, measures 42.3 by 63.5 centimetres, whereas the largest of the large photographs on view, Frankfurt, is 237 by 504 centimetres.

The monumental and the miniature are put side by side here so that Gursky can, for the first time, mount a full retrospective exhibition; this would be impossible with his large pictures. The Vancouver Art Gallery co-organized this show with the Kunstmuseen Krefeld in Germany and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, where the full complement of 130 works was shown. Gursky, who habitually lays out his own shows, pared down the original exhibition to fit the Vancouver space. At every venue, the photographs were presented in a different arrangement; Gursky sees each of them as its own world.

Rhine II pictures a contemporary river as a treatise on man’s control of nature, a landscape image that reads as straightedge geometry in a series of horizontal bands of colour and texture. The photograph is stunning large; it addresses the viewer’s body and perceptual senses. Yet it also reads at a more intimate size, which requires the viewer’s mental projection to enter its space. The size of the work affects its reception, of course, offering two different experiences. With the small prints, Gursky is returning his work to the realm of pre-big-picture photography, and he says he can imagine making small prints again in the future.

“For me, it was very interesting to think again about the sizes of the work,” says Gursky, who is 54 years old. “In the last years, I always produce the big works because I am accustomed to the size and because I normally work a very long time for one picture, and because I am showing in museums that ask for big sizes. The post-production sometimes takes a year and I am not working on so many different pictures at one time. In the last years, my production was more than before, but sometimes it is only three or four pictures a year.

“Now, because I have produced my whole body of work in a small size for the show in Krefeld, it has made me rethink size. I find that there are some of the big works which I show now as small ones that work very well, maybe even better than in the big size. It’s a new experience for me, and this is why I mix them all up.”

The personal character of this project, which seems like a taking stock of his career up to now, is reflected in the function that small prints of big photographs have had for Gursky. He has kept small prints around him in his studio and at home since he began to work with digital post-production in the mid-1990s. He shoots on film with a five-by-seven camera and scans images into the computer in order to retouch, manipulate and build them as montage.

“If you do so much post-production,” he says, “it takes such a long time to finish a picture. Normally, I don’t have the distance after this process to get the right feeling: is it a good picture, an okay picture, or a bad picture? So I need the pictures around me to prove the quality of the picture.

“The best situation to be confronted with your work is to come into a room or a space, and you don’t think about approaching your work, you just come from another world and you see it and you have an immediate emotion. This is the original reason to have pictures in the small size, but then I found they attracted me in the same way as the big pictures.

“The size of the work affects its reception, offering two different experiences: one immersive, one intimate.”

“In a way, the reading of the pictures is the same. Even if it’s a really big picture, if you want to get the details, you have to approach the picture and you read the picture line by line, and the same if you read a very tiny picture. For in a way, the tiny picture could be a detail of the big picture, no?”

Gursky also says that after 25 years of working the same way, he feels a bit bored. “I don’t have many choices in producing my work, so I take the photograph but the final result is always this [C-print mounted on] Plexiglas and it’s framed. On the one hand, I am happy that I found a solution that works very well for presentation; but on the other hand, I wish I could work with different materials. I’m a bit jealous of painting, where you have surface and the smell of paint. In my case, it’s always the same. So maybe this is the background for at least trying to make a difference between the sizes.

“But on the other hand, you could say the frames, you know, they are always wood and it’s not so important. I think it’s a good sign if you see an exhibition and you can’t remember the presentation, the pictures stay in your mind. Then I think it’s not so bad.”

Gursky, it would seem, is foremost a picture maker. This retrospective makes apparent as never before the encyclopedic scope of his immense, nearly single-handed project. It emphasizes the ways in which pictures within the whole relate to one another, both metaphorically and compositionally, and the strong abstract qualities of the compositions of his representational works, which refer to other photography and art forms such as painting. After all, a photographer can make or construct—rather than simply take—photographs about modern life, and produce them on the scale of painting. This is an approach to the medium he saw in the work of Jeff Wall, whose exhibition “Transparencies” he attended in Germany in the mid-1980s. Around the same time, Kasper König invited Wall to speak at the Kunstakademie Duesseldorf, where Gursky was studying with Bernd and Hilla Becher.

“This is what I learned from the Bechers,” Gursky says, speaking of the image Bahrain I. Although the perspective is aerial and the ground plane is steeply tilted (as in many Gursky photographs) and the composition forms an abstract pattern, there is a horizon line and a strip of sky. “My pictures normally have a sky and a ground, and it’s not only me. It’s also with Thomas Ruff [who was also a student of the Bechers],” Gursky says.

“If we photograph a building, the building stands on the ground. It’s not cut off. It’s a very conventional perspective but this—you can look at all my pictures—this is what we learned and what we think. It’s very important. If you would cut the picture, then it’s abstract [and closed off]. This way it looks more normal. You can find your own way into the picture.”

As Gursky says of his first encounter with Wall, “Because he showed his work very early in Germany, especially in Cologne, which is not far from where I live in Düsseldorf, I know him since 1986, very early. So, of course, he was really important for me and he is still very important for me. I must say he’s maybe the artist who inspires me or gives me the right push to work.

“Now I know what I have to do in my work, but when I was still a student I got lots of inspiration from him. There are some works that in a way are influenced by him. One piece, which is not in this exhibition [in Vancouver] is Giordano Bruno. I think, without knowing Jeff Wall, I would not have noticed this situation [two men, one old, one young, sitting on a bench on a sand dune in the Netherlands having an intense conversation about mathematics]. But with the difference that it is not posed.”

It seems reasonable to assume that Gursky also shares Wall’s idea that it is impossible to separate the human, the social and the economic. Gursky has dealt with these issues since he began his work, and they form one layer of its superstructure.

He focuses on places and on human beings in landscapes, built environments and crowds so enormous that people are tiny and anonymous. This is earth seen from Gursky’s famous distanced view, looking down like a Martian from above. People are at leisure, at work, at airports, at rock concerts, doing the things that people living in contemporary society do. What Gursky is seeking is a larger view than an individual picture can give, although each picture contributes to its perspective. It is a body of work that creates the critical image or meta-object, which this exhibition, part installation art and part photography, aims at presenting.

“Space is very important for me but in a more abstract way, I think,” Gursky says. “Maybe to try to understand not just that we are living in a certain building or in a certain location, but to become aware that we are living on a planet that is going at enormous speed through the universe. For me it’s more a synonym. I read a picture not for what’s really going on there, I read it more for what is going on in our world generally.”

His description of this existential condition is what he calls an “aggregate state,” a term used in the social sciences for a whole made up of smaller units. It is important to him, then, that his pictures, which combine reality and fiction, remain firmly tied to reality. “Even if a picture is completely invented or built, it’s necessary that you could imagine that it’s a realistic location or place. I am not happy if the picture looks completely surreal. Even if I am working with montage, I want that you don’t see it.”

The desert racecar track in Bahrain I is concrete on which a new course is painted for a different race every weekend. “This is why there are so many streets and it looks so bizarre,” Gursky says. “So it’s not, and this is very important, an invention of mine, it’s an invention of reality.” At the same time, the big picture, which Gursky shot from a helicopter, is a montage. “I fly in the helicopter for maybe two hours over the racetrack and shoot from different perspectives, so the middle of the picture is one shot, and then because of questions of composition, I make some changes and it makes a picture.”

Gursky has a large archive to draw upon for imagery, which he has culled from sources like newspapers, magazines and the Internet. “I collect images which surround us and, from time to time, I check all the images and then, because it is difficult to make a decision—because I don’t have the time or energy to follow everything that seems interesting—it’s a gamble to say okay, this project, I think we should start doing research on it.” He took a large-format camera with him to Vancouver, in case he saw something interesting, but said he probably would not use it because he no longer works this way when he travels.

“Normally, the way I work is that I’m doing research in the media, I find my location, do further research and then I’m asking for permissions. Then I travel to this place and I’m doing my work. I think I’m a very slow worker, so I focus on one picture and the background of the original idea for why I choose this location or this space is always a reference to a picture that I did before, but then I change the content a bit.”

The most recent big pictures in the exhibition are complete constructions made of many photographs taken in one or more locales, in some cases to create a narrative. Hamm, Bergwerk, Ost represents the “black room” at a coal mine near Düsseldorf where miners hoist their soiled work clothes and gear up to the ceiling on pulleys before going into the “white room,” where they put on their street clothes. The black room recalls the interior of a huge bat cave. It is a habitat that appears more animal than human. Gursky built the image from several photographs to present a close-up view of the suspended clothing that is true to the situation. “The whole picture is built,” he says, “but in a way that if you enter the space, it looks very similar.”

Hamm, Bergwerk, Ost and Frankfurt, a big picture of Frankfurt airport that shows migrants headed to the gates under a whole day’s worth of arrivals and departures on a huge board, indicates a new approach in Gursky’s work to social and geopolitical issues. These pictures, even in the representation of absent miners, take a closer look at people who can be recognized as individuals, as does the remarkable Cocoon II, in which there are a thousand people dancing. Gursky has an interest in electronic music and has photographed concerts and raves for more than a decade. The Cocoon Club, located in Frankfurt, is a famous nightclub designed by his friend, DJ Sven Väth. The Cocoon photographs, of which there are five, mark an unusual emphasis on one subject and the entry of personal references into Gursky’s work.

In one of the Cocoon photographs, which were recently shown at Frankfurt’s Moderne Kunst in his only exhibition devoted to a single subject, Gursky appears with his son. It’s his first self-portrait. The picture, Untitled XVI, is really less about about the club than it is an allegory of Gursky’s entire project. Fascinated by Cocoon’s interior walls, which resemble a futuristic hive, he built the hole-filled wall digitally using the software program of the architect who designed the club. Gursky initially thought of having DJs he knows in the picture, but took them out because the image was becoming “too narrative.”

He shows himself sitting on the floor and studying a small section of the “honeycomb” in relation to the whole wall in front of him. “It’s my studio in a way,” he says, “it’s the original floor of my studio and these details of the wall were printed details in the original size. I was preparing for an exhibition. In the end, I was so overwhelmed by the wall that I thought, ‘Okay, I have to appear in the picture and show how I think about constructing the picture.’”

Gursky’s son happened to walk into the studio and was added to the picture—like his father, he turns his head away from the camera—which contains other biographical references. Wooden blocks used to keep the bottom edges of large photographs off the floor are marked with the initials “MOMA” and are souvenirs of Gursky’s 2001 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. There are also stacks of CDs from Gursky’s collection along the bottom of the wall.

Such personal content would not have appeared in Gursky’s work even five years ago, but there is likely to be more to come and other changes besides. He is a bit tired of travelling, he says. Although he is in Vancouver because of this exhibition’s tour, he has decided not to show this year or the next in public or commercial galleries. All the work he is doing now will not lead automatically to exhibitions. “It is just to have the freedom to work,” he says, and he is doing this very close to home, where he is making an addition to his Herzog & de Meuron–designed house and studio.

“Right now I am building a huge storage area underground for my work and it has taken nearly two years for the construction. Because it’s still not working, because we don’t have the temperature and humidity we want, I got the idea to use it as a photograph. So I’m working on a photograph in my storage in the last weeks and I think this will also be a very personal picture.

“It’s exactly what I was working on the last two years. I will show part of my work in this picture, but in a very abstract way. In a way, it’s new because people will probably think I am travelling to foreign countries all over the globe. But in this case I am working in my garden—under my garden.” (750 Hornby Ave, Vancouver BC)

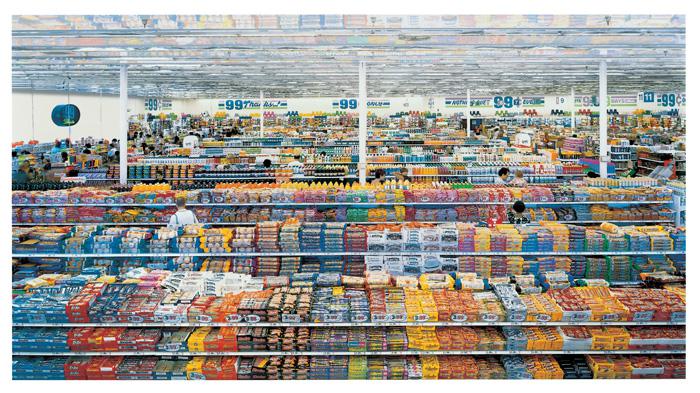

Andreas Gursky 99 Cent 1999 Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin / London © Andreas Gursky / SODRAC 2009

Andreas Gursky 99 Cent 1999 Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin / London © Andreas Gursky / SODRAC 2009