What bodies move alongside, within and outside of the designated city boundaries? Who inhabits the spaces along the city limits? How is the border of Calgary inscribed in the land and felt in space?

These were just some of the questions that artist Alana Bartol hoped to explore when she set out to walk Calgary’s city limits—estimated at roughly 174 kilometres long—earlier this year.

Bartol recently presented some of related “answers”—in the form of photographs, video and a talk—at Calgary’s New Gallery during the Mountain Standard Time Performative Arts Festival.

Walking is “a really great way to know a place,” says Bartol, who moved to Calgary last year from her hometown of Windsor. So that was part of her motivation for undertaking 11 long days of 10-hour-plus walks. (The days often stretched longer, actually, since Bartol frequently took public transit to and from the city boundaries.)

Another prompt to undertaking the huge project was the unique geography of Calgary itself.

“I was actually driving into Calgary on the Greyhound bus from Banff and thinking about the edge of the city, because it’s very defined in Calgary,” says Bartol. “It is so flat, and it’s the prairies, and coming out of the mountains you see that edge of the suburbs, and it just seems to be plopped in the middle of the prairies.”

At the New Gallery in Calgary in October, Alana Bartol presented photographic diptychs of objects found on her walk paired with views of landscapes along the city limits. Here is one such diptych, which includes a box for Plan B contraceptive. Photo: Alana Bartol.

At the New Gallery in Calgary in October, Alana Bartol presented photographic diptychs of objects found on her walk paired with views of landscapes along the city limits. Here is one such diptych, which includes a box for Plan B contraceptive. Photo: Alana Bartol.

What Bartol didn’t bet on when she started her walk: finding things like a Plan B contraceptive packages, an old passport and a sex doll washed up along barbed-wire fences; being followed by a man who kept trying to get her into his car; reassuring other drivers who stopped for her along the way that she didn’t need their help; trying to decide whether to trespass on large swaths of private land that the city limits seem to cross, and sometimes deciding against it; and being dive-bombed by a territorial osprey, or herded back down the path by a pack of dogs.

“A big part of the project for me was thinking about what was publicly accessible, and where bodies are allowed to move through public space, and how bodies are allowed to move,” Bartol says.

Bartol eventually decided to call the project A Woman Walking (The City Limits) to reflect some of the more gendered issues around this access to public space.

“A sex doll that was tangled very brutally in barbed wire”—found in the first few hours of the walk—“had a huge impact on my thinking about women walking alone and violence against women, and how the doll is a representation of an objectified woman, and she has been mangled and tossed and left in this fence,” says Bartol.

Pondering this image of violence, Bartol says also spent much of her walk thinking about missing and murdered Indigenous women.

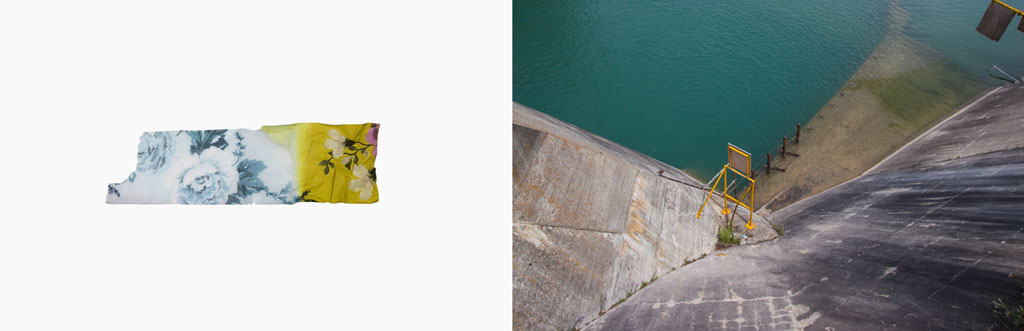

Another diptych by Alana Bartol juxtaposes an edge of the Bearspaw Dam in the Calgary suburbs with a scrap of flowered material. Photo: Alana Bartol. Courtesy the artist.

Another diptych by Alana Bartol juxtaposes an edge of the Bearspaw Dam in the Calgary suburbs with a scrap of flowered material. Photo: Alana Bartol. Courtesy the artist.

Certainly, issues around women walking have received a big chattering-classes boost this year with the publication of the books Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin and The Lonely City by Olivia Laing. The resurgence of Rebecca Solnit’s iconic Wanderlust: A History of Walking—which Bartol cites as an influence—is also notable.

But the way Bartol enacts these texts in space—and helps others do so as well—makes her practice distinctive.

For instance, in her collaborative water-dowsing walks Water-Witching for Wonderers (and Wanderers), Bartol tries “allowing people to move through the space in unsanctioned ways. The dowsing rod might point you in a direction where you might not usually go.”

Wandering community walks are also part of Bartol’s project Essential Oils (for Alberta), which turns foraged Alberta plants into infused oils, often through participatory workshops.

Another Calgary-city-limits diptych by Alana Bartol.

Another Calgary-city-limits diptych by Alana Bartol.

Issues of public space and public resources are also highlighted in Bartol’s ongoing Canada Council–funded project investigating abandoned Alberta oil wells.

“What has been incredible about that [oil wells] project is connecting with different landowners and learning more about the environmental issues, the legal issues, the socioeconomic issues connected to this problem,” Bartol says.

Bartol notes that dowsing is a form of divination that traditionally been used to find oil as well as water, offering a natural connection to her past practice. Bartol has also been working with the Orphan Well Association, a nonprofit unique to Alberta which remediates such wells.

“I would really like to have a component of adopting an abandoned oil well as part of this project,” Bartol says. “We all know about these issues but…it’s easy to distance ourselves if we’re not dealing with it directly.”

For November, Bartol is ensconsed in Prince George, British Columbia, where she is in a short-term residency with a unique project called the Neighbourhood Time Exchange.

“Basically, every hour an artist spends in their studio, the artist then spends an hour with a community partner,” explains Bartol of the Neighbourhood Time Exchange.

Bartol is looking forward to seeing where the community connections lead in Prince George this month. But wherever she goes, she will remember her epic Calgary walk, and its questions.

“If people are not walking, what does that say about our city or society or culture? What does that mean, when we say you are only supposed to walk in these areas?”

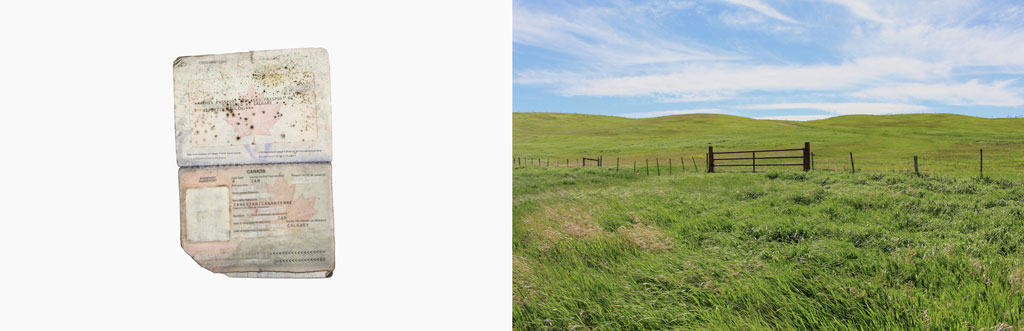

A Canadian passport discarded by the side of the road was another object culled on Alana Bartol’s journey around Calgary’s city limits. Photo: Alana Bartol.

A Canadian passport discarded by the side of the road was another object culled on Alana Bartol’s journey around Calgary’s city limits. Photo: Alana Bartol.

When she had just begun her long walk of Calgary's city limits, artist Alana Bartol found this sex doll wrapped up in a barbed wire fence. Its symbolism haunted the rest of her journey. Photo: Alana Bartol. Courtesy the artist.

When she had just begun her long walk of Calgary's city limits, artist Alana Bartol found this sex doll wrapped up in a barbed wire fence. Its symbolism haunted the rest of her journey. Photo: Alana Bartol. Courtesy the artist.