In our Spring 2014 issue, which is on newsstands from March 15 to June 14, curator and critic Philip Monk sets forth to tackle the work of late artist Arnaud Maggs (1926–2012). This is no easy task: Maggs’s work was never straightforward or linear. Like his early portrait subjects, Maggs was always turning. His work looked forward and back, sometimes simultaneously—it was collectorly, magpie-like and layered with references that remain personal and affecting. Musing on Maggs’s last body of work, the After Nadar series of 2012, Monk writes, “Much like Nadar, who was a man of shifting identities before settling into becoming a photographer, Maggs dramatically reinvents himself as his last artistic statement. And in reinventing himself, he invites us to revisit his past work and look at it anew.” We’ve endeavoured to do just that in this set of 10 key (though sometimes overlooked) works, honouring Maggs’s own penchant for re-presentation and re-collection.

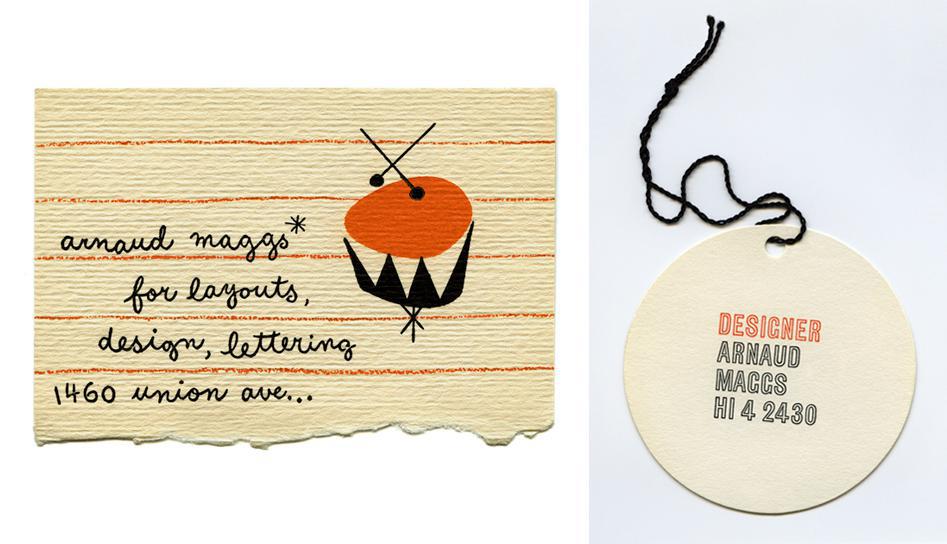

1. Designer business cards (1950, early 1960s)

Arnaud Maggs began his graphic design career in the late 1940s, and he saw no shortage of national and international success. In 1952, as a talented young professional with a small family, he moved from Montreal to New York to pursue a freelance career. He later worked in Milan, and by 1963 was working in Santa Fe with architect and designer Alexander Girard. His quirky, whimsical, clever and measured design practice highlights his diversity as an artist. Always fascinated with drawing and typography, Maggs’s business cards exude charm and imagination. More examples of Maggs’s early design work are available here.

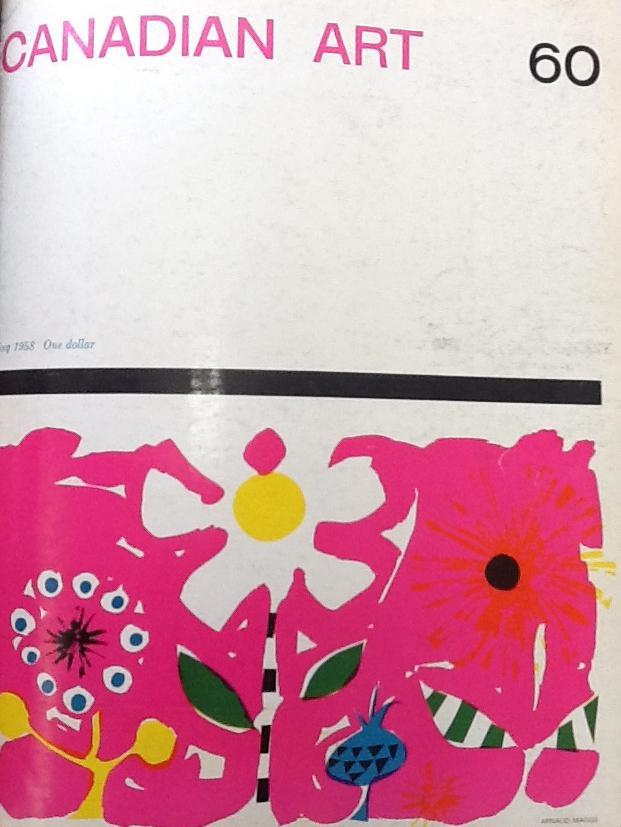

2. Canadian Art covers (1956 & 1958)

As a successful designer, Arnaud Maggs created covers for numerous magazines (including Chatelaine, Seventeen, Canadian Homes and Gardens), organizations (such as IBM and Unicef) and events (including the Stratford Festival, antique sales and circuses). His involvement with Canada’s art community was strong even in his early years as a designer. In 1956 and 1958, Maggs designed covers for Canadian Art. His Spring 1958 cover displays the sensitive, gestural, jubilant quality that made his design work so exciting—this sense of sensitive play laid the foundation for his career as an artist. Maggs continued to work as a designer until 1966, when his practice took a sudden shift and he adopted a career as a fashion photographer.

3. 48 Views (1981–82)

Maggs’s fashion photography career included work for Saturday Night, Maclean’s and Weekend. As a fashion photographer, Maggs shot pictures of some of Canada’s most important players, but by the mid-1970s, Maggs had given up fashion photography to devote himself to his artistic practice. His first series, 64 Portrait Studies (1976–78), collected images of 32 sitters, expressionless, naked, and pictured from the shoulders up, facing the camera and away from it. By the time he created 48 Views, the artist had returned to the heavy-hitters of the cultural scene: pictured in the series are personalities such as Yousuf Karsh (seen above), Jane Jacobs, Michael Snow, Ydessa Hendeles, John Ralston Saul and Adrienne Clarkson. Maggs’s work existed in dialogue with the practices that surrounded his own, and his homage to figures within the greater artistic community (backward and forward throughout history) became a mainstay of his career. In the Spring 1985 issue of Canadian Art, Gary Michael Dault perfectly encompassed what Maggs did in his early work. “What is most astonishing about Arnaud Maggs’s photographs,” Dault wrote, “is that they remain alive throughout all the obsessiveness of their making, that they are not killed by clarity.”

4. Hotel (1988)

As his career progressed, Maggs began to spend time in France, producing and researching new work—much of which dealt with found imagery and documents recovered from flea markets. During this time, his relationships to the taxonomies of visual symbols slowly shifted from categorizing portraiture to the visual symbolism of feeling and place. In Hotel, Maggs turned the camera to Paris’s hotel signs, which he photographed in series, each image presenting and re-presenting a symbolic convention. While the photographs resist the boundaries of language, they play with the organizing work of language and typography as mechanisms of meaning-making.

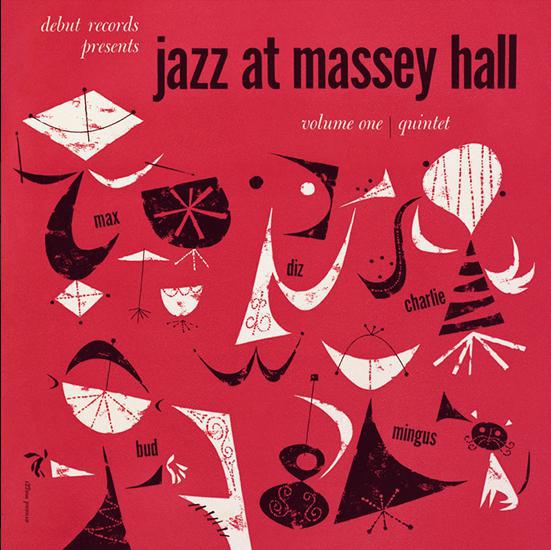

5. Jazz at Massey Hall cover (1953)

Maggs’s relationship with music and jazz was lifelong, and it permeated the boundaries of his art and life, in and out, forwards and back through history. While living in New York in 1953 and working as a designer, Maggs was invited to design the cover for Jazz at Massey Hall. He flagged this as memorable experience, writing, “It was exciting to meet [Charles] Mingus at his home and listen to the tapes with him. I created the cover on the subway ride back to my studio at 58 Park Avenue. Little did anyone know how famous this recording was to become.”

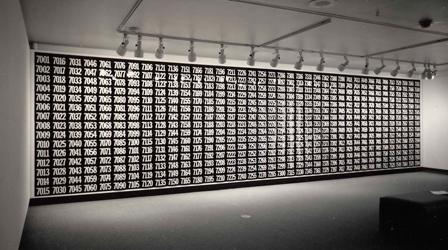

6. The Complete Prestige 12” Jazz Catalogue (1998)

By 1998, Maggs was revisiting his relationship to jazz records. In The Complete Prestige 12” Jazz Catalogue, Maggs ran a series of black and white images featuring the catalogue numbers of Prestige Records’ jazz releases. Referring back to his earlier grid-formatted portraits, this work, with its steady running-up of numbers, is a tally of time, classifying its movement towards an unnamed end. A review by Catherine Osborne in the Summer 1999 issue of Canadian Art described the work as kind of “sound work; an enormous audible map of 828 recordings.” Its referents consist not only of Maggs’s personal connection to music, but also the temporality of sound and the inexorability of time’s passage.

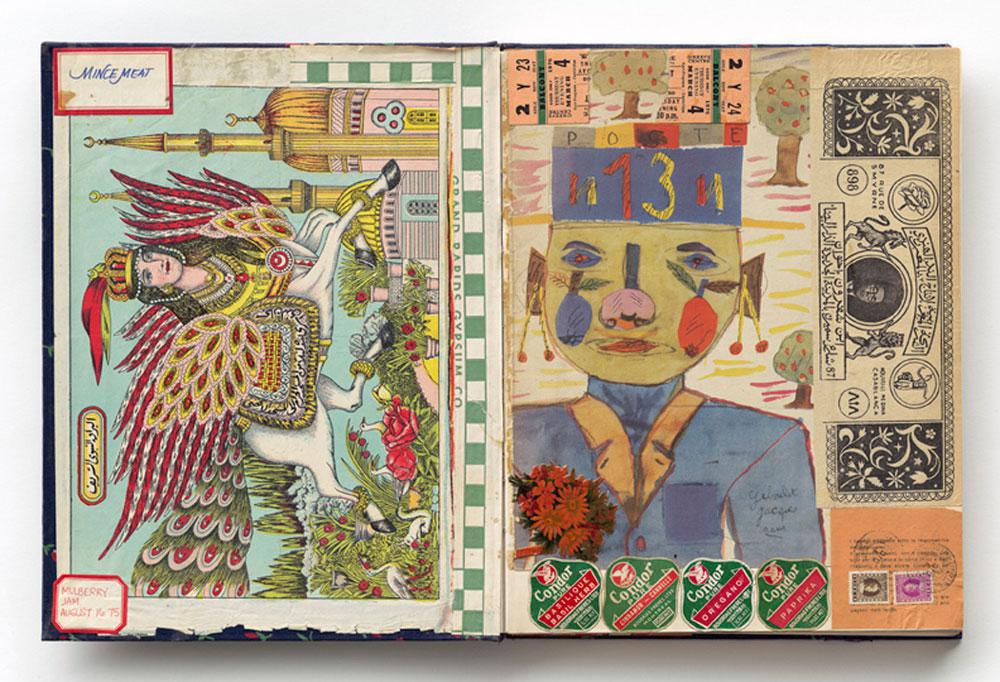

7. Scrapbook (2009)

In 1975, Maggs began accumulating material fragments of his own activities, his movements and his original drawings, as well as food labels, illustrations from advertisements, celebrity photographs and instructional images, in a scrapbook. After abandoning the unfinished scrapbooks, he re-discovered them, and more than 30 years later turned to photographing them. The photographs offer a glimpse into Maggs’s personal archive, and also into his ongoing interest in cataloguing and classifying the visual lexicon of the everyday. Maggs’s own scrapbooks, in his hands three decades later, became a document of a stranger—a former, now inaccessible self. The scrapbook images document the reinvention, recollection and revisiting that have come to characterize Maggs’s work.

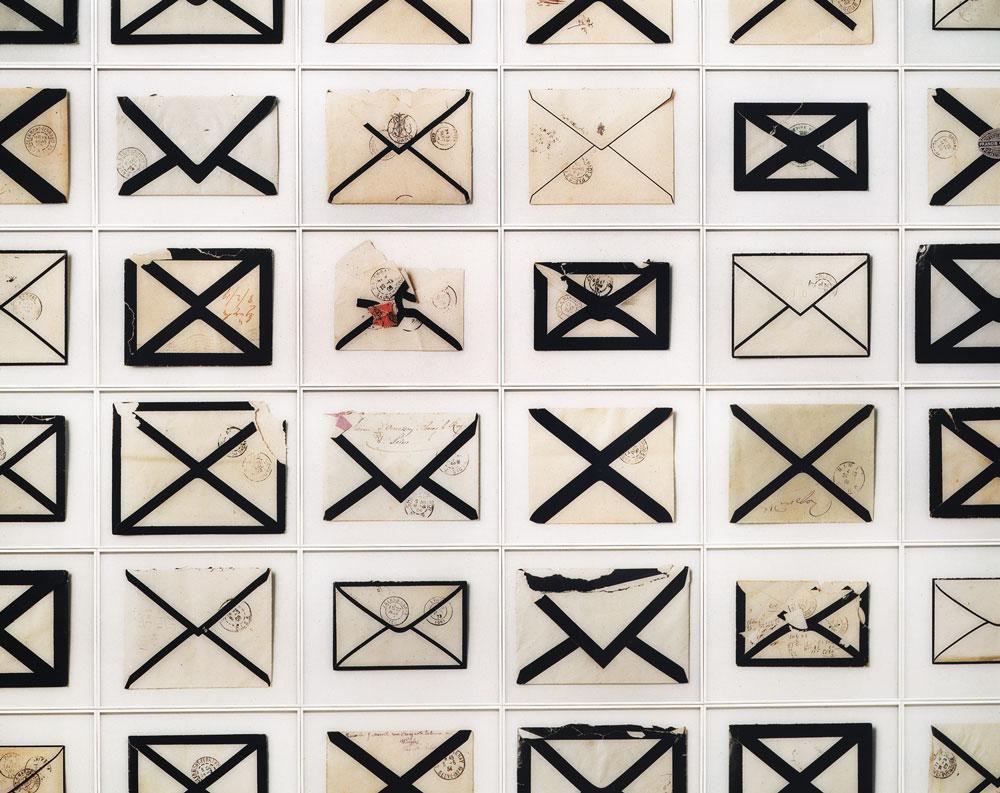

8. Notification (1996)

In this series, Maggs turned his systematic photographic eye to mourning stationery. The black-crossed envelopes which overwhelm the viewer in each instalment of his Notification series are artifactual and documentary: their subjects are unassuming relics, sent in the 19th century to alert a friend or family member of someone’s passing, or to correspond during a grief-ridden period. For Kate Taylor, who wrote a feature article on Arnaud Maggs for Canadian Art’s Winter 1996 issue, these works were some of his most moving. “Known for unemotional multiple images of people, numbers and hotel signs,” she wrote, “Maggs has added heart-wrenching content to his art without abandoning his rigorous approach to form. At seventy, Maggs had produced his best work ever.”

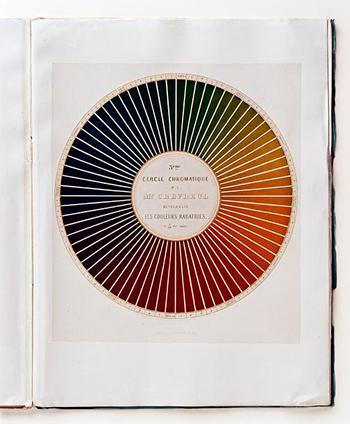

9. Cercles chromatiques de M. E. Chevreul (2006)

It’s fitting that Maggs turned to Chevreul to explore the nature of documenting colour, but his inclination toward Chevreul also did double duty as a gesture to life, loss and homage near the end of his career. There is also a prescient nod in Maggs’s adoption of Chevreul given his later work on Nadar: In 1886, at the age of 100, Chevreul was interviewed by Felix Nadar as his son, Paul, took accompanying photographs. It has been called the first photo-interview in history, and came just three years before Chevreul’s death. The Cercles images pick up on Maggs’s preoccupation with the taxonomy of life and death, and his parallel cataloguing of the work of colour and form.

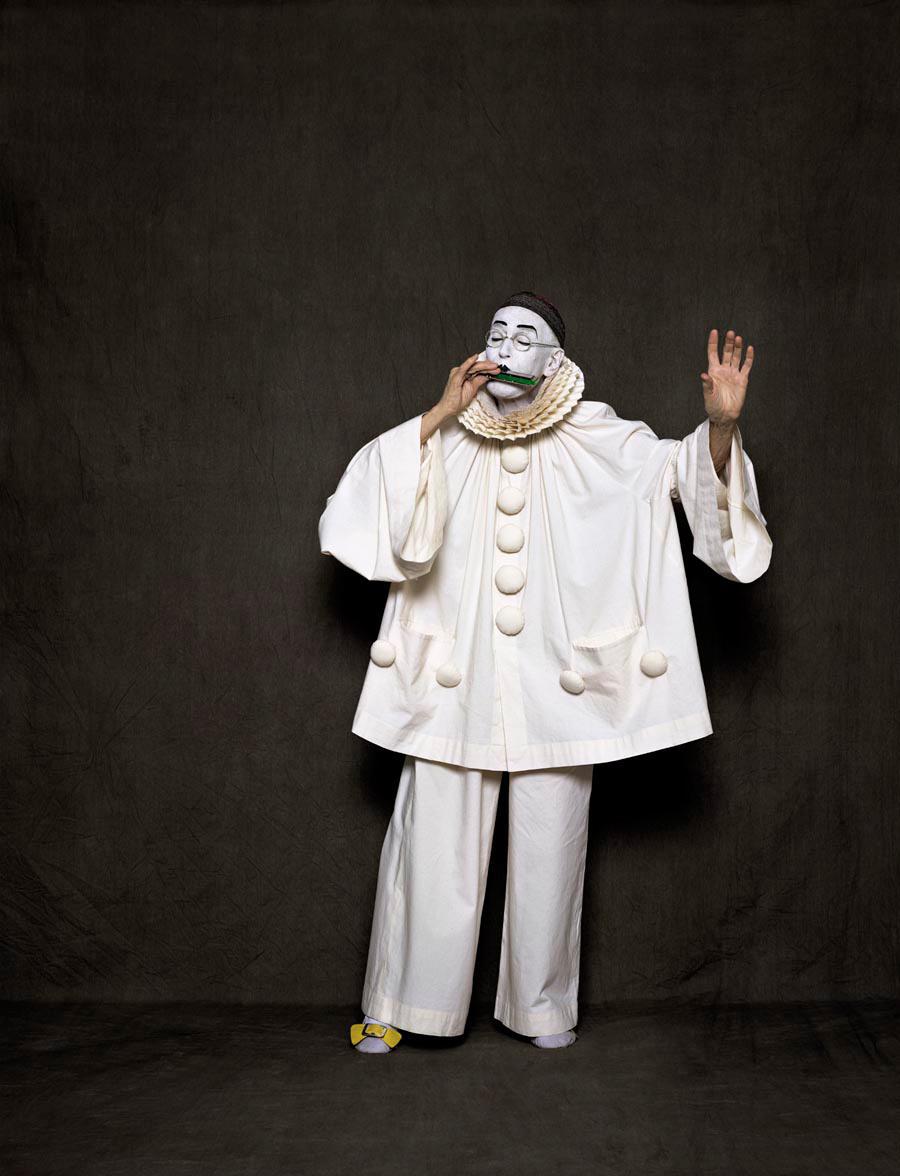

10. After Nadar (2012)

As Philip Monk describes in his feature article on Maggs in our Spring 2014 issue, Maggs’s After Nadar series is richly layered with historical and personal meaning, reconstructing what it means for Maggs to come after photographers like Nadar, and examining his performance of self and archive in front of the camera. Monk describes Maggs’s performances as Pierrot in the series as miming out two dimensions of his identity: the professional and the personal. For Monk, Maggs’s photographs represent a bold re-imagining of his own life and work at the end of his career. “We see Maggs/Pierrot as an archivist of his own production,” Monk writes, “facing tottering stacks of archival boxes, sizing up his history and holding in his hands an image of his earlier ‘other’: one of his stock self-portraits, from decades previous.” These gestures of making, naming, miming, collecting and recollecting, Monk suggests, were at the heart of Maggs’s practice.

All images in this post, except for #2, are © Estate of Arnaud Maggs and provided courtesy of Susan Hobbs Gallery.