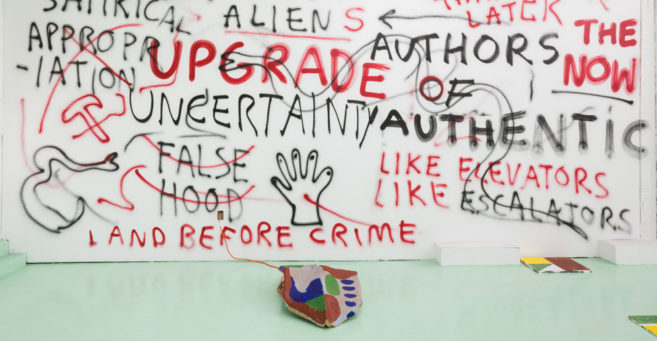

In Patrick Cruz’s recent solo show, “Titig Kayumanggi (Brown Gaze)” at Plug In ICA, his frenetic, colourful paintings covered the entire floor, tracing the artist’s own history of immigration from the Philippines to Canada. The unstretched, unprimed canvases were portraits, landscapes and abstract works. There were individual lines you could pick out and follow as well as one big piece that melded together, depending on where you looked.

On the surrounding white walls, thick black ink had been directly applied in the shapes of symbols, their lines dripping down into each other, encouraging the brain to continually attempt connections to find meaning. Being in this space did not give me rest; I felt I had to hold onto the bits of understanding I could find in an overwhelming visual cacophony.

Patrick Cruz, “Titig Kayumanggi (Brown Gaze),” 2017. Installation view at Plug In ICA. Photo: Karen Asher.

Patrick Cruz, “Titig Kayumanggi (Brown Gaze),” 2017. Installation view at Plug In ICA. Photo: Karen Asher.

When I couldn’t understand the symbols on the walls and window, I looked to the things that were clear to me: symbols on boxes piled in the space. In a globalized world, many of our universal symbols are based in capitalism, like the logos of booze and mass-produced goods with disparate countries of origin stamped on their sides.

I couldn’t just wander through this show. The sheer physicality of this chock-full exhibition invited viewers to break codified gallery expectations by marking the artworks with their shoes through entering the space. The artwork is therefore made special, but also everyday, enter-able (literally accessible), suggesting that Cruz’s work belongs everywhere, and asserting a new structure that questions control, the creation of culture and the language of power in the space of the gallery.

Ray Fenwick, “A Greenhouse. Evening.,” 2017. Installation view at Plug In ICA. Photo: Karen Asher.

Ray Fenwick, “A Greenhouse. Evening.,” 2017. Installation view at Plug In ICA. Photo: Karen Asher.

Just next door to Cruz’s wall-to-wall installation was an exhibition that appeared, at first glance, to be its minimal opposite: “A Greenhouse. Evening.” by Ray Fenwick.

Walking into the dark gallery, visitors first encounter a small building, where the odd architecture of an awkward slope played double duty as a roof and a screen onto which an animation is projected. Rows of plants in pots matured and mutated in the animation, and their cartoony forms, which seemed familiar but also impossible, were accompanied by muffled “growing” sounds made by a human mouth. Walking around to the back of the structure, the only option was a door.

Fenwick is a performance artist but, present and participating as he was during this solo exhibition at Plug In ICA, his body was invisible to the gallery visitor. Stepping through the door into the green glow of the dark greenhouse space led to the first of many destabilizing questions: Is the artist present? Am I alone? No. There is a voice surrounding me. If I respond to the voice, am I talking to a disembodied person? To the plants? To myself? Are any of these acceptable choices?

Ray Fenwick, “A Greenhouse. Evening.,” 2017. Installation view at Plug In ICA. Photo: Karen Asher.

Ray Fenwick, “A Greenhouse. Evening.,” 2017. Installation view at Plug In ICA. Photo: Karen Asher.

The mirthful items on view in the greenhouse eased the existential questions raised by the space’s destabilizing feeling. There was a single chair in the clutter of plants, and next to it a tape player with a pile of cassettes for viewers to choose from: “SQUEAL MADE SUCKING AIR THROUGH LITTLE APERTURE AT SIDE OF LIPS WITH JUST RIGHT AMOUNT OF MOISTURE,” “SQUEAKY WET SQUEAL SUCKING AIR BETWEEN TOP TEETH AND BOTTOM LIP,” “HIGH CLOSED-MOUTH HUM W/SMALL MORSE-CODE ‘MUP’S MADE BY OPENING MOUTH,” “YOU CAN’T GIVE UP/I WON’T GIVE UP – HUMMING, SINGING, WET POPS,” etc. Are the sounds on the tapes the sounds of my internal growth, I wondered, like the plants in the animation outside? No, that would be weird. Are they noise to affect and accompany the growth of the real plants surrounding me? Is this voice trying to interact with me meant to be the “voice of god”?

The more time I spent inside my mind within the greenhouse, the more this unusual meditation felt comforting. I adjusted to the “conversation,” to this way of sitting with myself, the plants, the voice. Fenwick successfully cajoled me into considering the strangeness of expectation around communication with the self, others, deities, living things in the world. Being in the greenhouse felt like coming to an exciting sort of peace with the ambiguous absurdity of existence, like the human condition could maybe be kind of magical instead of fucking terrifying.

Kristin Nelson’s exhibition “Dear Cheryl” recently occupied window gallery, Winnipeg’s only 24-hour artist-run centre, with a poignant letter to a mysterious stranger known to all Winnipeggers: Cheryl Lashek, the director of Inspection and Technical Services Manitoba, whose signature appears in a little framed inspection sheet in every elevator in Winnipeg. The street-level, human-sized window was filled with a grey moving blanket, the kind that you’d see covering the inside of an elevator for protection. Stitched on the dirty blanket in script made of sequins:

Dear

Cheryl Lashek

let

us

down

easy.

The poetic missive evokes Cheryl through the very font of her own, ubiquitous signature, which shares space with elevator riders throughout the city and reassures them that she has checked things out, that she has been here in this very place and that everything is going to be fine.

The paradox of Cheryl’s familiarity is one we encounter often, for instance with celebrities, but don’t generally name: the feeling of knowing someone without ever having met them. A personality might be conjured based on the most minute of details. Cheryl’s personably impersonal existence is infused into the laser-printed digital scrawl, and the signature becoming a stand-in for a companion you may share several rides with each day. Bizarrely, shortly after Nelson’s work appeared in window gallery, two Cheryl Lashek fan accounts appeared on Instagram, further complicating the confused lines of privacy between the public and this regular person.

At Urban Shaman, “Traces,” a recent exhibition curated by Becca Taylor, beautifully delineated the gallery’s space into thirds. Three performances accumulated their marks on the gallery spaces, on the artists, and on the visitors as the show played out. Working with the concept of Indigenous presence and erasure within urban contexts, the very physical works created for and during the exhibition were a testament to and a celebration of the many methods of Indigenous community building and resistance.

At the show’s launch, artist Dion Kaszas was set up to offer tattoos to gallery visitors. As a professional extension of his artistic practice, Kaszas made linear marks, evocative of a horizon line, a path walked, a thread connecting, across wrists of willing participants. Working with skin as canvas was a practice of Kaszas’ Nlaka’pamux ancestors and was generously shared in this contemporary context. Kaszas created visual as well as physical ties through the act of breaking through skin and drawing blood.

The live work of tattooing took place over the course of just one evening, but a large screen in the centre third of the gallery showed video of the intimate work of inking skin throughout the exhibition. Observing such a visceral act is no less than intense, but through continued watching, beyond the wince-inducing pokes, what comes through is the shared vulnerability of the participants: for Kaszas, this vulnerability is the labour of reviving, sharing and encouraging the future of this tattooing tradition, and for the person being tattooed, it is the very opening of their flesh in a public space to share in the meaning of this work.

Winnipeg artist Jaime Black works with concepts of matrilineal connection to land. In her performance between us, Black transplanted movements that she would normally carry out as part of performance on the land into the urban environment, featuring ersatz elements of nature, such as rocks and landscape projected onto a blanket, with bare wood supports for a floating wall.

Moving through the space with fellow artist Niki Little, Black shared a blanket that they dipped in a metal tub of water, washed the space with, and wrapped themselves in together, pulling or pushing each other as they connected through the cloth.

The meditation of the washing of space, of themselves and each other, felt like a double-edged sword, where this dance moved around and teased out the line between cleansing and erasing, and the relationship of these actions to memory and identity. Beyond the performance, what remained in the space was a trail of rocks that led to Black’s video, projected on the blanket; the imprints of the land repeated through the echoes of the natural in a built environment.

For the third piece, Tanya Lukin Linklater worked with Marcus Merasty and Arlo Reva. The two performers sparked the space with a labour-intensive, physically and emotionally exhausting action choreographed by Lukin Linklater. Dressed similarly and wearing their long, dark hair loose, the artists began by grasping the walls and working towards jumping higher, but became defeated in the effort. The speed of the performance ebbed and flowed this way throughout, the force of their energy giving way to exhaustion over and over again.

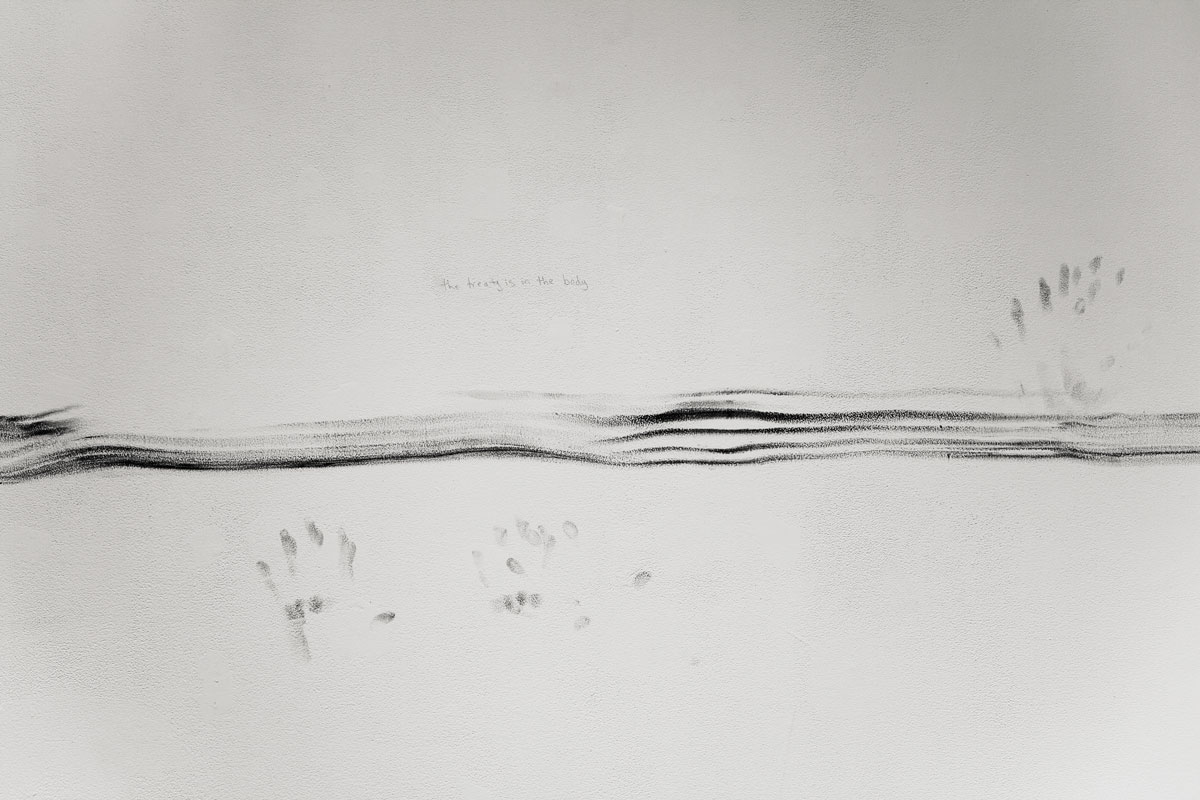

Along the entire length of the white walls, one artist traced a line with a handful of charcoal that the other continued with the remnants rubbed into their hand, repeating and reinforcing each other’s marks. They ran at each other, connected briefly, then lost the connection through the force of their movements.

The bodily dialogue evoked real physical struggle, pressing against the wall of people gathered to watch and forcing the audience into a strange trepidation where, sharing the air and space so closely with the panting performers, it was impossible not to feel my own body responding to the effects of the heat and being pulled into the action.

Visiting the gallery later, the minimal remnants of the performance spoke volumes: a sketchy charcoal horizon line full of scratches and fingerprints spanning the gallery, and a new note in pencil above it: “the treaty is in the body.”

Letch Kinloch is an arts administrator and founder of Also As Well Too Artist Book Library in Winnipeg.

A detail of Tanya Lukin Linklater’s artwork in “Traces” at Urban Shaman.

A detail of Tanya Lukin Linklater’s artwork in “Traces” at Urban Shaman.

This post was changed on July 5, 2017. The editors of the original post included an Instagram embed of a Dion Kaszas tattoo that was created in Winnipeg—but that was not created as part of the “Traces” project and exhibition. That image has since been replaced in the post with an Instagram embed directly related to the May 4 Dion Kaszas tattooing event at “Traces.” We regret any confusion resulting from the original image embed.