“Lost!” Kain the Poet exclaims as he holds up an antique African doll in his hands, then ceremoniously wraps its eyes in an ochre-coloured cloth and sets it down amid a display of other objects acquired through colonial dispossession—tattered maps, astrolabes, porcelain figurines. Technicians move around him and matter-of-factly process historical artifacts in the opening scenes of Vincent Meessen’s video Ultramarine (2018), which documents Kain’s encounter with, and response to, European plunder of Africa. A member of the Black nationalist Last Poets group during the late 1960s, Kain improvises a narrated exhibition of the objects in what he calls a “collage of texts, images, and drums.” Projected onto a tapestry of sewn-together blue cloth swatches, the moving images are marked by a series of striations throughout. Like the tapestry, the video is an interweaving of spoken word and blues performance with museological undertakings. It perpetually references its own material fabrication as well as the construction of historical narratives.

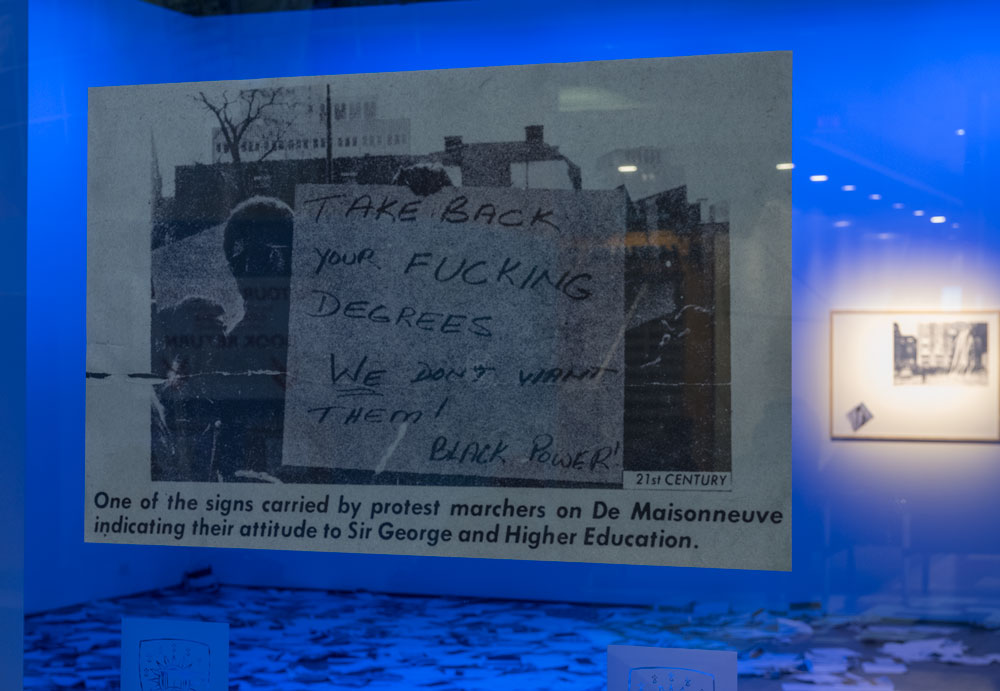

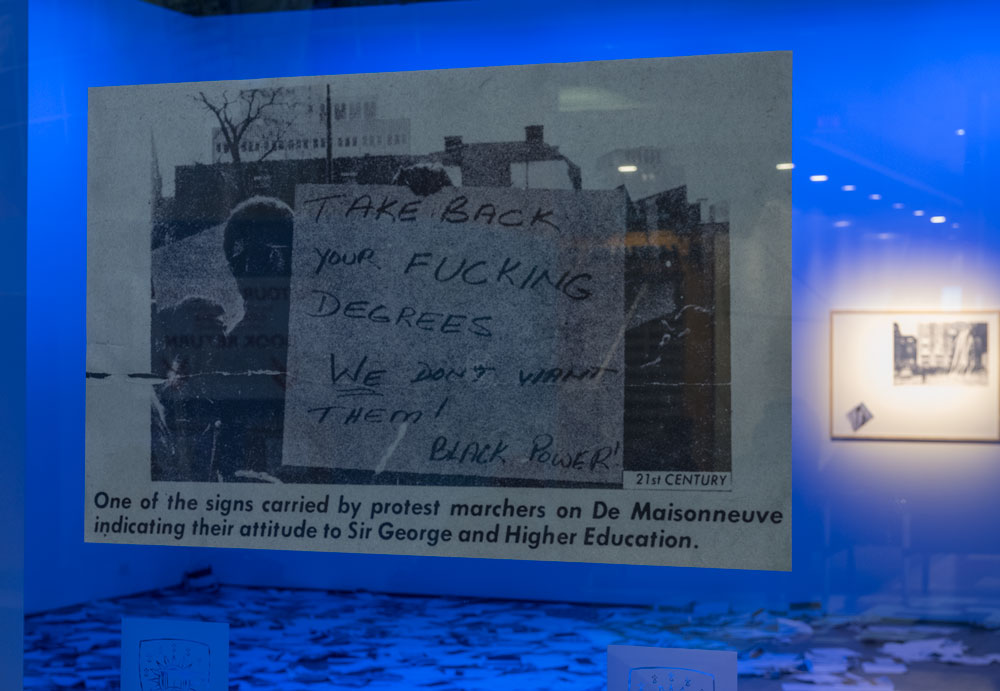

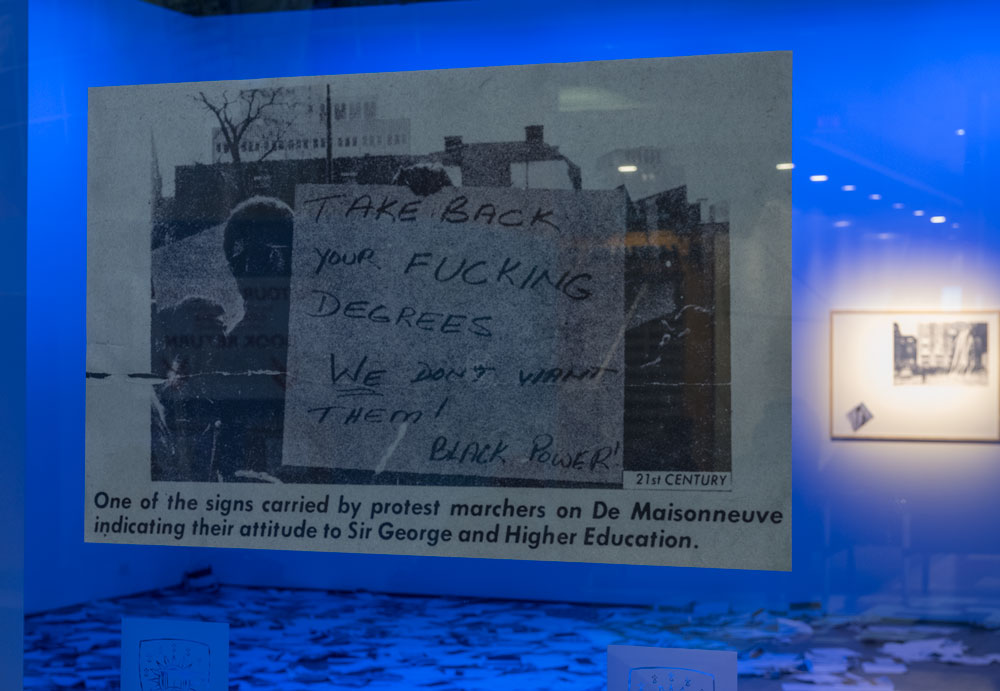

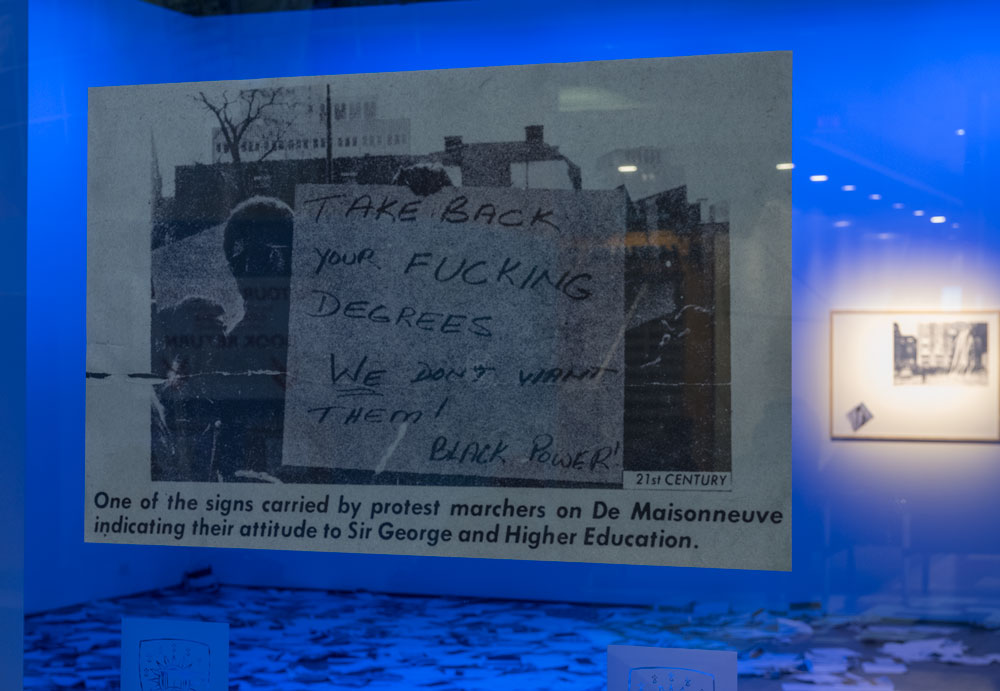

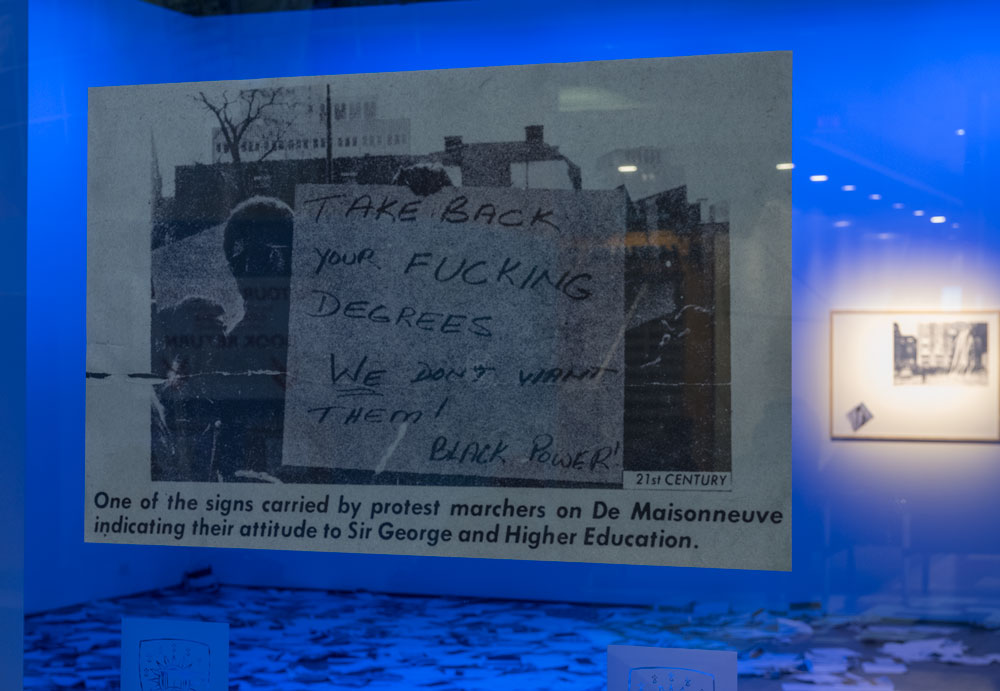

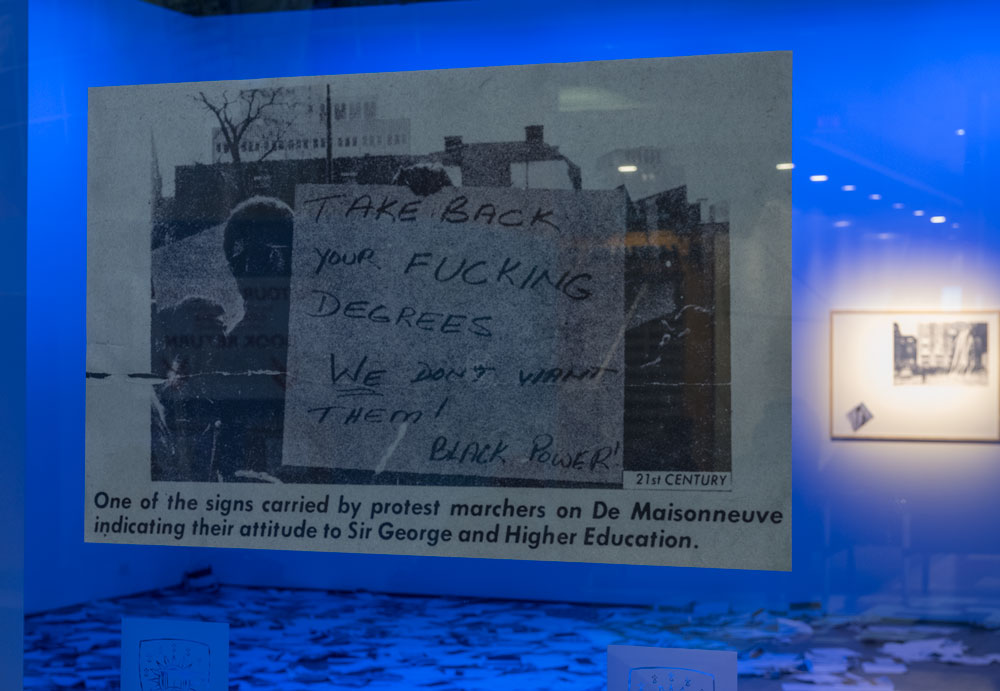

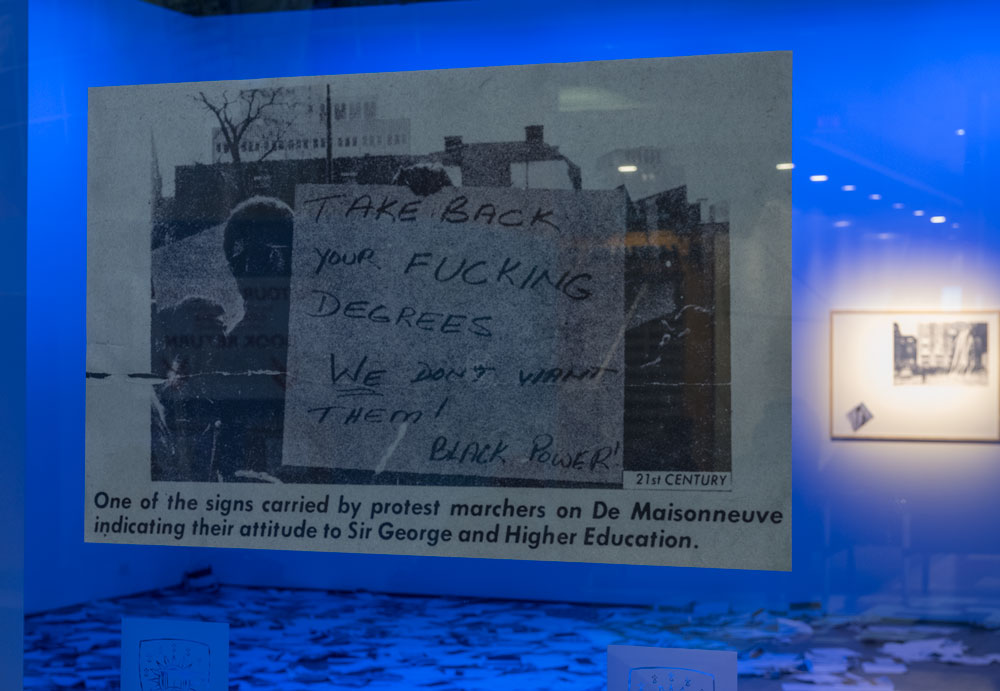

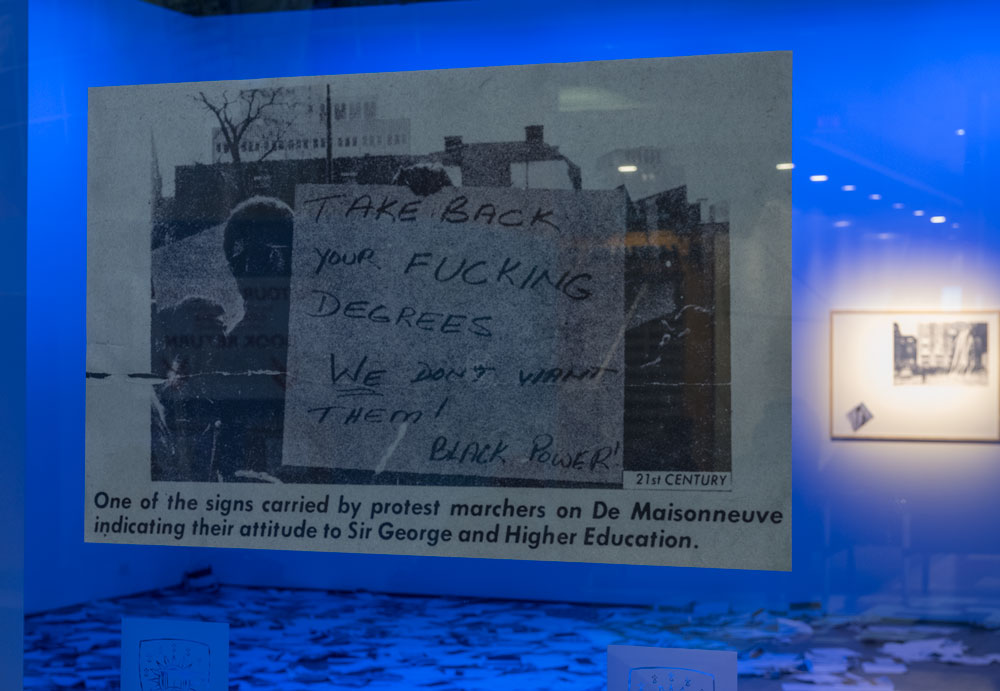

Ultramarine sets into motion an array of cultural associations that route through the remaining works in Meessen’s “Blues Klair,” the Belgian artist’s first solo exhibition in North America. These works, in turn, create a localized context for the video and textile installation, rooting it in Montreal. Discordia (2018), for instance, explores the 1969 “Computer Riot,” the 13 days during which hundreds of students occupied the computer lab at Sir George Williams University (known now as Concordia University, where the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery is located) to protest—among other things—the university’s refusal to address allegations regarding a professor’s discrimination against Black Caribbean students. Directly adjacent, New Canadians (2018) centres a map made by Fundi, the Jamaican Situationist and union activist, that connects contemporaneous anti-racist uprisings throughout the West Indies to the Montreal riot. Within this constellation, Meessen adds a series of works—Postface (2018), Index (2018), Sans Issue (2018) and Straram’s Trama (2018)—that emerges from his ongoing research into the margins of Situationist aesthetics and their application in former French colonies. These four works—a playscript, an annotated abecedarium, a photograph and a small geometrical drawing blown up to cover two gallery walls—all re-envision and extend a particular trace Meessen encountered in the Montreal archives of the French exile and Quebecois Situationist Patrick Straram.

Curated by Michèle Thériault, the works in “Blues Klair” are riveting in that they immerse visitors in a series of constructed environments, each one offering a provocative counter-narrative to Eurocentric history and historiography. Meessen’s work sets a high standard for research-creation art practices. Yet, of critical importance, Meessen’s work points to these entwined histories without resolving or even acknowledging the possible asymmetries between the white Belgian artist and his explorations of global Black cultural production. As engaging as the works are, one is left with questions: What are the artist’s relations to the collaborators and contexts of his research over time? Might recognizing these asymmetries in the work itself help in the project of recalling and resisting hegemonic narratives, rather than reproducing them?

Vincent Meessen, 21st Century, 2018. Installation view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Blues Klair, 2018. Exhibition view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Ultramarine, 2018. Installation view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Ultramarine, 2018. Installation view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Blues Klair, 2018. Exhibition view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Blues Klair, 2018. Exhibition view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Blues Klair, 2018. Exhibition view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Blues Klair, 2018. Exhibition view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Ultramarine, 2018. Installation view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.

Vincent Meessen, Ultramarine, 2018. Installation view, Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery. Photo: Paul Litherland / Studio Lux.